When Your Friends Get Eaten In Front of You

Most would lose all hope. This man didn't.

Two weeks ago, I released a 2.5 hour interview with Dr. Fernando Cervantes, a descendant of Miguel de Cervantes and the greatest living historian of the conquistadors. (You can watch it here)

Shortly after the 53:00 mark in our conversation, Dr. Cervantes mentioned the name of one of the most remarkable, yet practically unknown, people to ever venture into the New World: Gerónimo de Aguilar. Of all the stories of daring and adventure to come out of this era of history, few have moved me more than his.

Today, I want to briefly tell Aguilar’s story, in the hopes it A) encourages you to watch the full interview with Dr. Cervantes, and B) serves as inspiration for the next time you face down a seemingly impossible struggle. Aguilar’s story, after all, is one of faith and survival in the face of all odds, and a powerful reminder that God’s plan for you — even in the face of utter disaster — might still be greater than anything you could ever imagine…

Cages & Cannibalism

Géronimo de Aguilar was born in the south of Spain in 1489. While still in his youth, he took vows to become a Franciscan friar, and in 1510 — at the age of just 21 — he found himself in the New World, at the colony of Darién in modern-day Panama.

In the spring of 1511, a dispute broke out between settlers, and Aguilar was entrusted to travel to Santo Domingo in Hispaniola to inform the governor there of the state of affairs. But disaster struck when his ship hit shoals off the coast of Jamaica: although Aguilar made it into a rowboat, currents soon carried him over 590 miles away to the coast of the Yucatán peninsula.

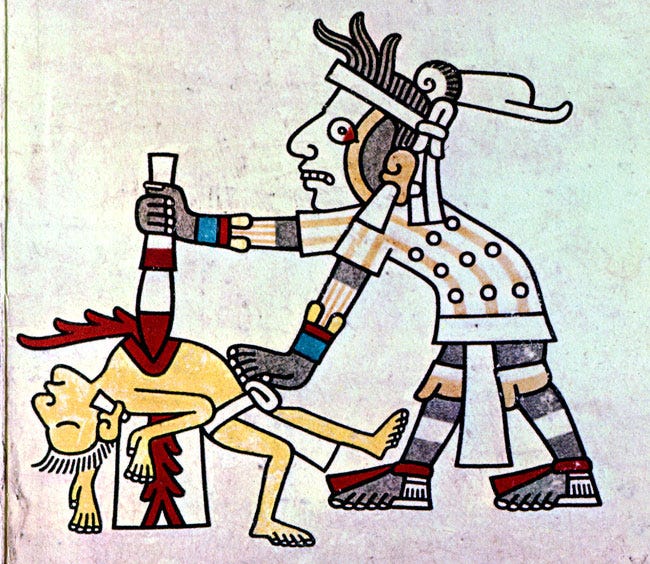

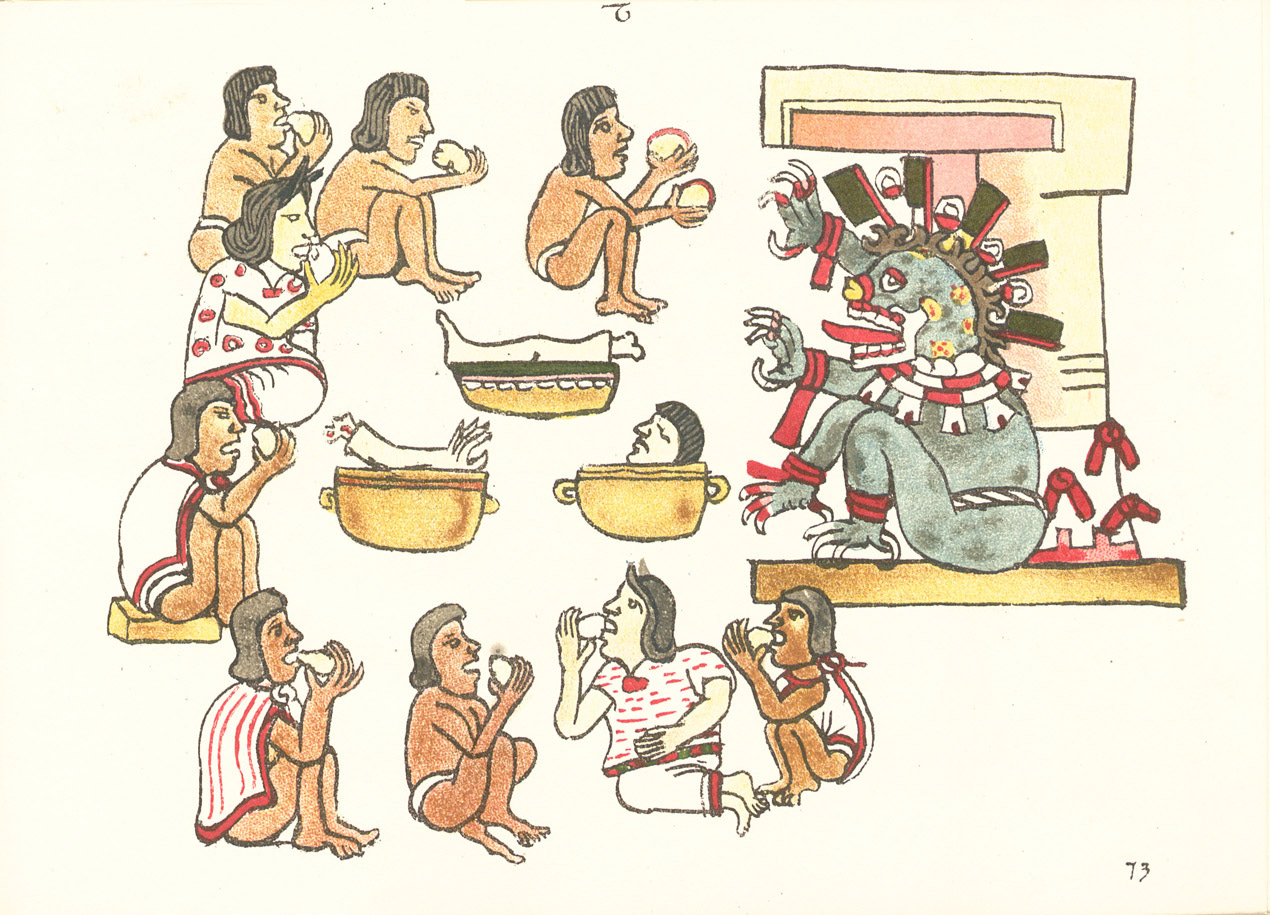

There, Aguilar and his comrades were captured by a local cacique warlord and thrown into cages to be fattened. Five men had been sacrificed and eaten before Aguilar and a small group of others managed to escape — but their relief was short lived, as they were soon captured by a rival warlord named Xamanzana…

Temptation & Despair

For the next eight years, Aguilar was enslaved to Xamanzana. During that time, any already miniscule hope of rescue he and his fellow Spaniards still had was crushed: they were quite literally off the map, trapped in a nightmare world of violent intertribal rivalry and human sacrifice.

Some Spaniards reacted by “going native”: one man named Gonzalo Guerrero, for example, took a Maya wife and fathered three children by her. Tattooing his hands and face and piercing his ears and nose, Guerrero became a faithful servant of Xamanzana. For the rest of his life, his loyalties lay with his new tribe and family, and he eventually died fighting against the Spanish in Honduras 25 years later.

Yet remarkably, Aguilar never succumbed to the same depths of despair as his fellow countrymen. Refusing all the native women offered to him by Xamanzana, he stayed faithful to the vows he had taken as a young Franciscan friar. He found consolation in his breviary, which he used for daily recitation of the divine hours.

So faithful was he to his breviary that when he finally escaped and reunited with Spaniards eight years later, his guess of the date was only three days off. The story of what transpired during and after that reunion is what we’ll look at next — for it’s a powerful reminder that even your most painful experiences can be transformed and redeemed beyond your wildest dreams…

Encounter with Cortés

Gentlemen. Are you Christians? Whose subjects are you?

-Aguilar to Cortés, March 1519

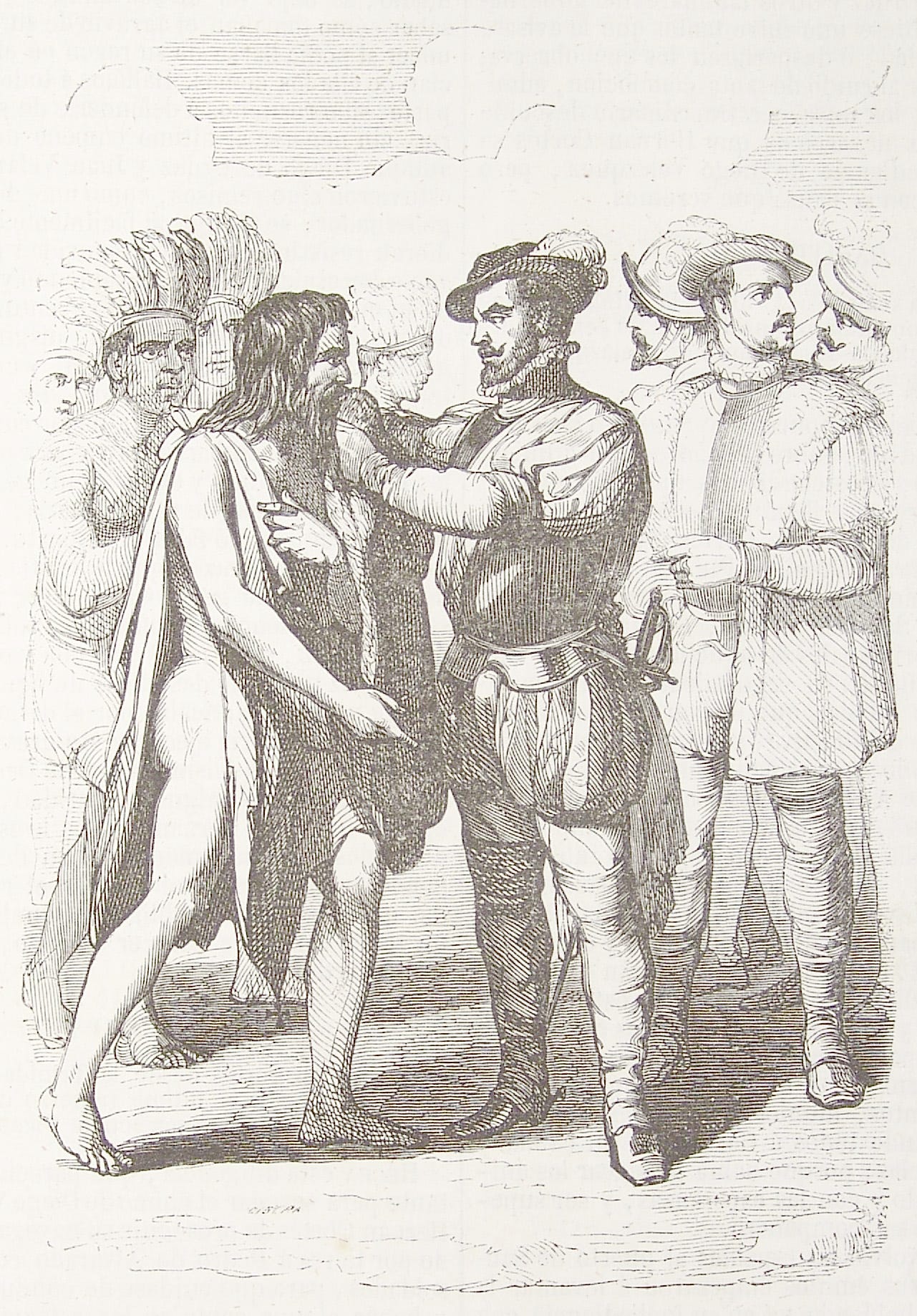

Having returned to the island of Cozumel to repair a leaking brigantine, Hernán Cortés awoke one morning to a strange sight: a canoe approaching from the Mexican mainland, carrying three men clothed only in loincloths, and their hair “tied as women’s hair is tied.” Armed with bows and arrows, the men arrived on shore and disembarked from their canoe. Seeing that they wanted to speak, Cortés cautiously rose to meet them.

What happened next he simply could not believe: one of the three men approached him, and then in Cortes’s own native Castilian declared: “Gentlemen. Are you Christians? Whose subjects are you?” Cortes gave his reply, and the man — Aguilar — burst into tears. He implored Cortés to join him in giving thanks to God, for he knew their meeting to be providential.

Aguilar sat down with Cortés to recount what had happened over the past eight years, and all that he had endured. He informed Cortés that during his captivity, he had learned the Mayan language, a fact which made both men feel a profound significance in their meeting: Cortés viewed it as though God had sent him an interpreter, and Aguilar believed he finally understood his purpose — the reason why he had been allowed to endure those eight miserable years in servitude…

The Key to the Americas

Yet for as remarkable as their meeting was, neither man could then fully comprehend the true weight of it. By that point, Cortés was still largely unaware of the Aztec (Mexica) presence in the interior of Mexico, for his movements were confined to the periphery of Mexico’s eastern coast. Sailing between Yucatán, Cozumel and the Islas Mujeres, he had encountered only the Mayan people.

The watershed moment came later that same month, when Cortés and his men were attacked by locals after landing on the Mexican mainland. The Spanish emerged victorious after taking the town of Potonchan, and there they discovered another treasure unlike any other — a girl named Malinche (later called Marina) who was fluent in both Maya and Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs and the lingua franca of central Mexico.

A line of communication was quickly established: Cortés spoke to Aguilar in Castillian, Aguilar to Marina in Mayan, and Marina to the locals in Nahuatl. With this, the two great empires — Aztec and Spanish Habsburg — could now speak openly with each other. And, in true poetic fashion, the bridge spanning this (former) linguistic divide was composed of none other than a humble servant girl and a previously enslaved friar.

“Deeds Hitherto Thought Impossible”

The significance of Aguilar’s life in shaping the course of history needs no explanation. But to Aguilar himself, the thought of ever doing such a thing would have been unimaginable. Think of him toiling away during those eight years in captivity: believing himself lost, forgotten, not even a footnote of history. Everyone and everything of significance to him were continents aways, slowly fading into the fog of his memory as the years passed by.

And yet, he did not despair. He faithfully upheld his vows and followed his breviary, even in the face of all odds. It is precisely because he did so that, nearly a decade later, the impossible became reality.

To listen to my full 2.5 hour video interview with Dr. Cervantes, click the link below:

Contrast this history with the artistic bilge emanating from Neil Young, fantastically covered by Grace Potter and Joe Satriani. So much artistic beauty, so little historical truth

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=paeNnR33i5Q&list=RDpaeNnR33i5Q&start_radio=1&pp=ygUrY29ydGV6IHRoZSBraWxsZXIgZ3JhY2UgcG90dGVyIGpvZSBzYXRyaWFuaaAHAdIHCQkDCgGHKiGM7w%3D%3D

This is incredible. Just found this. thanks for sharing. I'm from El Salvador, so all the stuff about my ancestors hits heavy. I am so, so thankful the Lord sent the Europeans to rescue us.