The Man Who Refused to Accept Decline

How Venice reversed her greatest humiliation...

When describing the condition of the contemporary Western world, many would, for readily understandable reasons, use the expression “in decline”. But is ‘decline’ a state of being, or a state of mind?

While it would seem ludicrous to us today, there were, after all, prominent thinkers alive during the Pax Romana who earnestly believed that things had never been worse. A certain degree of cynicism towards the present is natural, but there is no question that societies traverse phases of confidence, and others of despair.

In the later 17th century, the Republic of Venice was such an example of the latter. Once the commercial conqueror of the West, the Venetian Rialto at its height was the Wall Street and City of London of its day. With the growth of the European overseas empires, however, the world’s trade lanes had shifted to the oceans, Italy was no longer an essential stepping stone, and the end of crusading fervour had rendered the eastern Mediterranean geopolitically stagnant.

Slowly, but surely, Venice was bleeding the territories of her once great empire to the ascendent Ottoman Turks. In 1669, after an expensive 24 year war, she lost her last great possession beyond the Adriatic — the island of Crete. It was a painful moment for all patriotic Venetians, including her most talented admiral, Francesco Morosini.

A generation later, however, Morosini would avenge the loss of Crete in stunning style. Vanquishing the Turks, in 1687 he secures Venice’s greatest conquest in almost half a millennium, throwing his country an astounding lifeline.

Here is how the last great Doge of Venice demonstrated that decline need not be inevitable, and what he can teach you about responding to personal or national humiliation…

But first — we’re going to Italy!

This coming May, we’re hosting two exciting retreats to Bergamo and Venice. To learn more and apply to join us, click the button below:

Now, back to the article…

The Cretan Quagmire

If there was a state which embodied the expression ‘punching above one’s weight’ more than any other, the Republic of Venice was certainly among the top contenders.

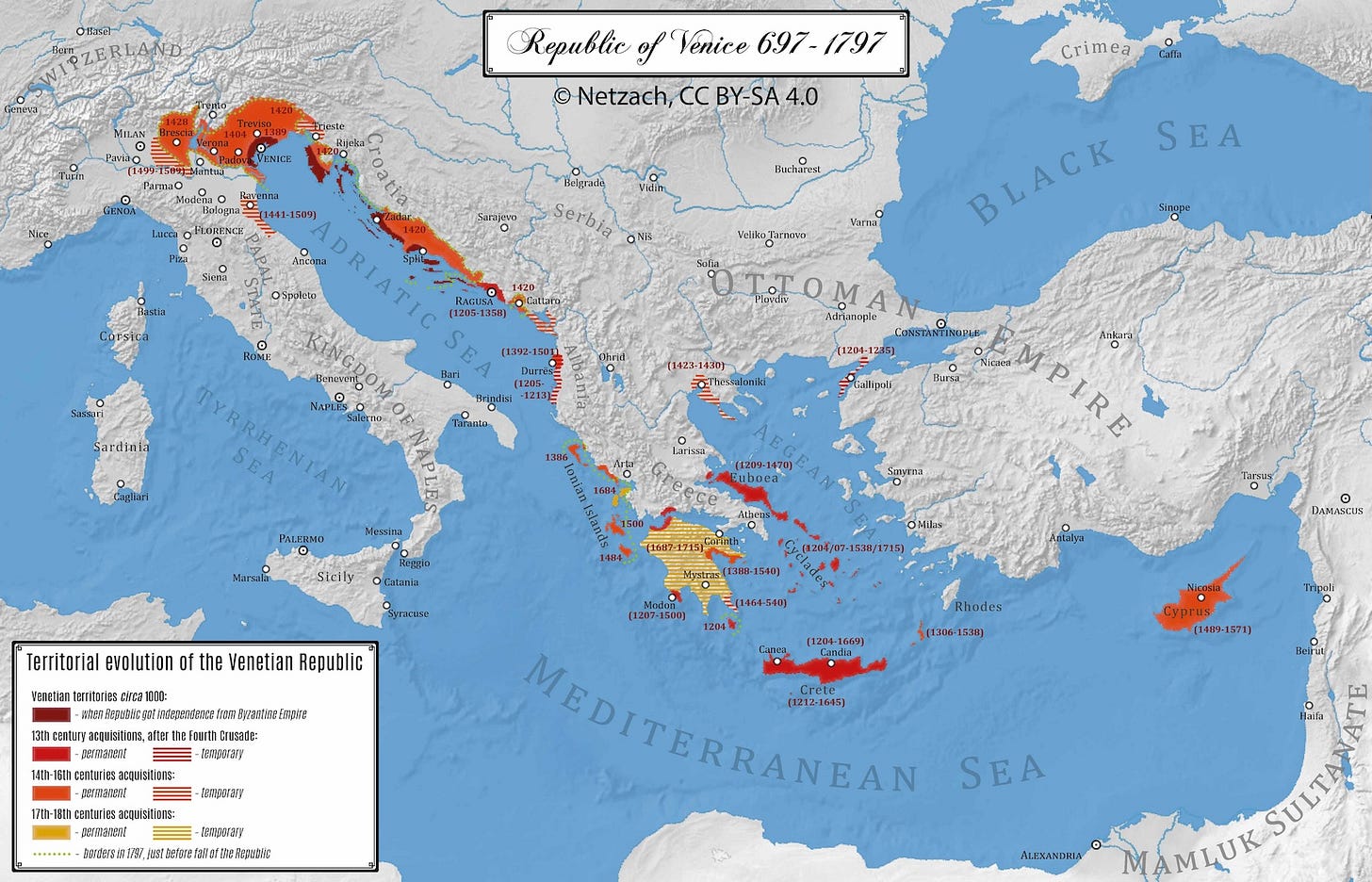

Based out of a once unsanitary and malaria-ridden lagoon, over the centuries a small fishing colony of Roman exiles exploded into a maritime empire that spanned half the Mediterranean, and controlled the commerce of much of it. In 1204, unquestionably heinous and pursued out of naked self-interest though it was, by the Fourth Crusade she all but destroyed the Eastern Roman Empire and established a protectorate over much of Greece.

It was indeed amid that infamous campaign that Venice acquired her first major overseas colony — Crete, the lynchpin of any power that wished to control the Eastern Mediterranean.

By the 17th century however, those days seemed long ago indeed. Many states in the West had since consolidated into great powers, and near all the east was now subject to the Ottoman Empire, whose aggressive expansion had felled countless Christian armies and principalities. Venice had fought many wars against the Turks, and emerged maimed from all of them. Each defeat, and each loss of land, only made the next war more grueling, and its result more humiliating. Venetian life now, it seemed, was a perverse waiting game for the next inevitable disaster.

It was into this sorry state of affairs that Francesco Morosini was born on the 26th February 1619 to the ancient Venetian House of Morosini. Descended from a line that had produced three Doges of Venice, two Queens and many a cardinal, expectation weighed heavily upon him indeed.

It is a sign of the foresightedness of the Morosini however that Francesco was not educated in the traditional manner of a Venetian merchant, instead being sent to the new military academy of San Carlo at Modena, where he would study alongside the sons of martial nobility. War would define his life, and much of it trying desperately to defend his faltering country.

Just 21 when he was appointed a galley captain in the Venetian navy, he would be allowed just four years of relative normalcy before the hammer struck. Following a foolish provocation by the Knights of Malta, who then took refuge on Venetian Crete, in 1645 the enraged Sultan Ibrahim declared war on Venice, resolving to dismember her empire once and for all.

Thus on the 30th April 1645, a mighty armada of 400 ships, loaded with 50,000 men, sailed from Constantinople directly for Crete. With much of Christian Europe tied down in the Thirty Years’ War, Venice had little hope of finding meaningful allies. Panic ensued, as the parish churches of the Republic called for all families to donate to the war effort. Prestigious offices were auctioned off, and admittance to the nobility itself could now be bought. Anything and everything which could raise money was done, no matter how many traditions they trampled.

Unable to resist the Turkish onslaught on land, the Venetian forces on Crete withdrew to the capital city of Candia, where in the summer of 1647, one of the most gruelling sieges in human history began. That the besieged would resist for a full twenty two years however, is testament to the bravery and determination of a Venice even in decline.

Throughout all of this, Morosini was rapidly baptised in war across the Aegean theatre. On the 10th July 1651, his capture of a 60 gun Ottoman warship at Triò earned him renown, while the ferocity of the war, and frequent death of Venetian commanders, enabled his steady promotion.

To his immense frustration, Venetian high command was prone to irresponsible risk-taking, banking on large-scale engagements to try and destroy the Ottoman fleet outright. Morosini, however, favoured the Fabian strategy of dismantling the Turkish supply lines through limited precision strikes. While the Venetian navy would indeed score technically impressive victories, they would too often come at too high a cost. Inevitably, after one gamble too many, on the 19th June 1657 the Ottomans shattered the Venetian navy in the Dardanelles, killing Supreme Admiral Lorenzo Marcello in the process.

With Crete now wide open, the Republic turned in desperation to Morosini, who on the 20th August 1657 was promoted to Capitano Generale da Mar. What seemed like a great honour, however, was a poisoned chalice…

The Darkest Hour

Supreme Admiral Morosini inherited an appalling situation. Over a decade of all-out war had severely depleted the resources he could call upon, and with them he was now expected to cancel out a litany of strategic failures.

His task was not helped either by Provveditore Generale Antonio Barbaro continually diverting supplies away from the navy to futile land operations. Nevertheless, on the 8th March 1668 Morosini executed a masterful night-attack on an Ottoman flotilla off the island of Standia. With five enemy vessels captured, and over two thousand Christian slaves liberated, it was a momentary illusion of glory, earning the Admiral the title of Knight of Saint Mark.

But with Venice spending a crippling 4,392,000 ducats on the war in 1668 alone, Morosini knew that a war of attrition would only favour the Sultan. Occasional arrivals of ‘help’ from Western Europe, too, were more of a hindrance than a help, as the contingents were often poorly coordinated and unprepared for the quality of Ottoman gunnery. They would also have an alarming tendency to withdraw from the theatre at the slightest reversal, leaving nothing but further depleted rations in Candia.

In June 1669, when a contingent of Louis XIV arrived, a promising start swiftly descended into farce, when a stray shot ignited a cache of gunpowder barrels, sparking panic among the French that the entire terrain was mined. On the 24th July a recklessly captained French warship was destroyed by Turkish shore batteries, and within a month the entire force was gone.

With his garrison reduced to just 3,600 men, and realising that there was no hope of any further reinforcements that year, Morosini decided to take matters into his own hands. Knowing that the Senate had debated the possibility of negotiated peace several times in the past, but was too proud and too slow to follow through, the Admiral chose to bypass the chain of command, and settle directly with the Turks.

Fighting for Crete was by now a lost cause, and the only choice that remained was between losing everything, or possibly salvaging something. Thus, on the 6th September 1669, Francesco Morosini placed his reputation, and even freedom, on the line by illegally signing a treaty on behalf of his government. Morosini would of course have to surrender the island, but in exchange, on account of the respect that the Turks had for him, the Admiral extracted valuable concessions — continued possession of certain other bases, and the salvation of the island’s artistic and archival treasures, as well as the lives of the civilian population, who were furthermore free to leave for Venetian territory.

It was a respectable peace, and the best that could realistically have been achieved. Nevertheless, by the terms of the treaty, on the 26th September 1669, 465 years of Venetian presence in Crete ended.

Morosini’s enemies among the Venetian political class, many of whom bore direct responsibility for the war’s outcome, were outraged. Manoeuvring at once to project their own failures onto him, a vast smear campaign was assembled to cast the beleaguered admiral as ‘the man who lost the empire’. Moreover, to sell the message and further deflect blame, factions in the Council formally accused Morosini of embezzlement of public funds.

On top of that, the loss of Venice’s largest colony, compounded with her titanic war debts, would plunge the Republic into economic ruin that took decades to recover from. It was the end of an era, and a disaster beyond compare. Morosini had fought for his country, been ignored in all the moments when he could have made a difference, and made a scapegoat for the errors of others.

Years of painful wilderness followed. The one ray of light was his acquittal of criminal charges, though this occurred only when the advance of the investigations threatened to implicate powerful people who had actually embezzled public money, and who pressured the trial into shutting down. Yet Morosini, weathering these humiliations, knew that for all the intrigues in Venice, the true enemy would not remain in the background for long.

In 1683, the Ottomans, now at the apex of their power, launched an invasion of the Holy Roman Empire itself, striking at the capital of Vienna. As the weeks passed, and the plight of the Christian West grew ever more acute, the now sixty four year old Francesco Morosini could well have slipped into quiet retirement, accompanied by resentment and despair at just how much had gone wrong.

What he did instead would demonstrate the power of sticking to your values, and seal his immortality as one of Venice’s greatest heroes…