Does How You Dress Matter?

The aristocratic case for why style can make or break others' perception of you...

“The fool adorns himself, and the elegant man gets dressed”

Honoré de Balzac, Treatise on Elegant Living

In an age where the majority of men, from the Americas to Oceania, have been condemned to the business suit, the resulting vacuum in ‘fashion’ was inevitably going to be occupied by excess.

“I’m not fashion-conscious” is the understandable and inevitable reaction of the grounded modern man, faced as he is online and in print by daily images of celebrity extravagance and provocative marketing, stemming all too often as they do from the same individuals and organisations who simultaneously push questionable political and cultural messaging.

The neglect of one’s appearance, however, is an overcorrection. It is one that our forebears, who understood all too well that appearance does indeed matter, condemned no less than they did vanity. It is also a theme central to one of the most influential books ever written — Count Baldassarre Castiglione’s Il Cortegiano, or The Book of the Courtier. First printed in 1528, it takes as its subject the qualities of the ideal ‘courtier’, from manners to martial pursuits and the art of conversation and courtship, to the power of ornament and dress.

As the most immediate manifestation of appearance, clothing is a frequent theme in Il Cortegiano, from the point of view of both how and why to dress well. Today, we explore what Castiglione can teach you about the duty to present yourself elegantly — and how to avoid vanity in the process...

PS — Today’s article is free for all readers! If you enjoy what you read, please consider sharing it with a friend.

To receive articles like this twice weekly, click below to become a premium member:

The Nobility of Grace

“Outward things often give knowledge of those within”

Baldassarre Castiglione, The Book of the Courtier, II.28

Written as if a conversation between Elisabetta Gonzaga, Duchess of Urbino, and the learned gentlemen of the court, Il Cortegiano seeks to understand, quite simply, what makes the ‘perfect courtier’, and by extension, the perfect gentlemen. Across four books, the conversation turns to almost every element of interpersonal relations, and how the ideal courtier might best shape them for both virtue and advantage.

Baldassarre Castiglione himself, as a man well-accustomed to the many languages of power, wrote Il Cortegiano with great authority. Born the son of a minor nobleman in 1478, he would mature during the violent opening of the Italian Wars, and serve as a diplomat at the courts of a succession of sovereigns, from the Marquis of Mantua to the Holy Roman Emperor and the Pope himself.

Yet among his many extraordinary appointments, it was indeed at the court of Urbino that Castiglione’s heart truly lay. The splendour of Urbino, after all, lay in intellect as much as the arts, and it was here where the Italian Renaissance found its most sincere patrons in the Montefeltro dukes. As a result, though Castiglione’s great work would be printed in Venice in 1528, the setting of Il Cortegiano in the Urbino of 1507 is no random eccentricity.

A recurring word in Il Cortegiano is grazia, or ‘grace’, a word that would come to define both the court of Urbino — the birthplace of Castiglione’s close friend, the painter Raphael — and the Italian Renaissance itself. Seeking to explain where ‘grace’ comes from, Castiglione coined a word of his own — Sprezzatura. One of those magnificent terms that has no equivalent translation in English, Castiglione defines sprezzatura as follows:

“To practise in everything a certain nonchalance that shall conceal design and show that what is done and said is done without effort and almost without thought”

Baldassarre Castiglione, The Book of the Courtier I.26

The essence of sprezzatura, therefore, lies in the balance between 'show' and 'be'. ‘Grace’, as a consequence, might be explained simply as the art of making the difficult appear natural.

So what is this balance in the context of clothing specifically, and what are the consequences of upsetting said balance?

The External Bears Witness to the Internal

Being as it is one of the first influences upon our judgment of a person, dress is one of the many subjects to which Castiglione devotes particular attention in Il Cortegiano.

It is introduced however in a rather bold manner midway through Book II, after the gentlemen acknowledge that it is foolish to get carried away debating the art of conversation, when dress “is universally more practised and a man more often finds himself engaged in it”. That is, it is the impression created by dress which likely shapes the initial conversation between two people as yet unfamiliar with each other, and often determines whether conversation even occurs at all:

“There are however some simpletons, who, even in the company of the best friend they have in the world, on meeting a man who is better dressed, at once attach themselves to him, and then if they happen on one still better dressed, they do the like to him. And later, when the prince is passing through the squares or churches or other public places, they elbow their way past everyone until they reach his side: and even if they have naught to say to him, they still must talk, and go on babbling, and laugh and clap their hands and head, to show they have business of importance, so that the crowd may see them in favour.”

Baldassarre Castiglione, The Book of the Courtier II.25

Only the perception of a man who is truly holy, or truly dishonest, is immune to the influence of dress. It has the power to override our better judgement and indeed the virtues we would otherwise preach and hope to practise. It has the power to draw and to avert the eye, and subconsciously shape our fundamental assumptions of the wearer, from their social standing and wealth to their competence, regardless of the truth.

As if anticipating the politically correct reaction to such a statement, Castiglione has one of the gentlemen, Cesare Gonzaga, scoff at this notion, asserting that “if a gentleman is of worth in other things, his attire will never enhance or lessen his reputation”. To this, Sir Federico Fregoso responds with harsh truth:

“‘You say truly,’ replied messer Federico. ‘Yet what one of us is there, who, on seeing a gentleman pass by with a garment on his back quartered in divers colours, or with a mass of strings and knotted ribbons and cross lacings, does not take him for a fool or a buffoon?’”

Baldassare Castiglione, The Book of the Courtier, II.27

Whether you accept it or not, therefore, you will be judged by others on your appearance, and that judgement will play an enormous role in how open or not they will be to your other qualities.

Before any other detail of his clothing, however, what first distinguishes the gentleman at a distance is of course colour, and its suitability for the occasion:

“And this I say of ordinary attire, for there is no doubt that bright and cheerful colours are more suitable over armour, and for gala use also dress may be fringed, showy and magnificent; likewise on public occasions, such as festivals, shows, masquerades, and the like. For such garments carry with them a certain liveliness and gaiety that accord very well with arms and sports. But for the rest I would have our Courtier’s dress display that sobriety which the Spanish nation greatly affect, for things external often bear witness to the things within”

Baldassare Castiglione, The Book of the Courtier, II.27

A man who dresses informally can only expect to be addressed informally. Should a man arrive at an occasion dressed as if for another, he is signalling to those present that while his body is there, his attention is elsewhere, and so too his priorities.

The gentleman, therefore, dresses in a manner indicative of how he would like to be treated. While Castiglione fully acknowledges that the appropriacy of colour is context-sensitive, a reliable solution for almost any occasion is black, which instinctively implies seriousness:

“Moreover I always like them to tend a little towards the grave and sober rather than the garish. Thus I think black is more suitable for garments than any other colour is; and if it is not black, let it at least be somewhat dark”

Baldassare Castiglione, The Book of the Courtier, II.27

It is indeed no coincidence that many of the most prominent fashion designers and businessmen of our own times rarely wear bright colours when speaking publicly.

What you wear, however, is only half of a battle which is otherwise determined by how you wear it…

The Danger of Affectation

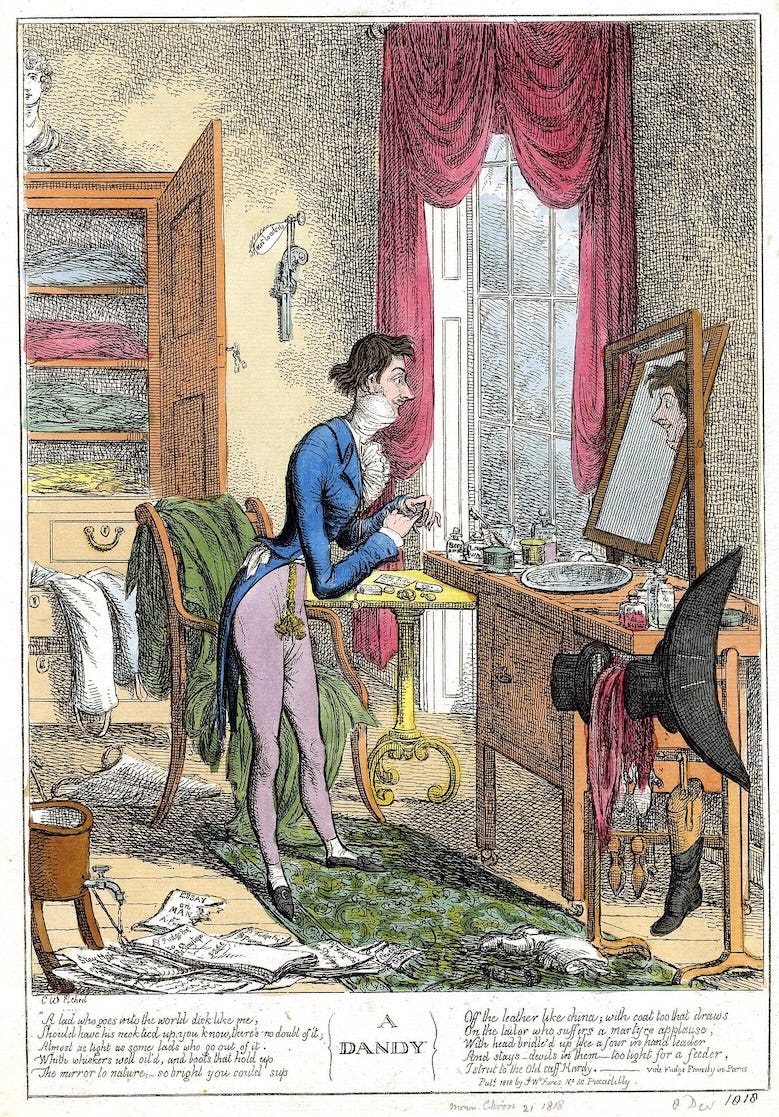

‘Dress to impress’ is a fickle motto. The colour and cut of clothing is, after all, meaningless if they are incompatible with the wearer’s character, or the impression they wish to give.

The majority of men can instinctively tell whether ornament is outweighing function, and vice versa, and when it does, the effect is repelling rather than alluring. A critical element of sprezzatura, indeed, is the confidence exuded by a person who is comfortable in what they are wearing. A lack of confidence betrays affectation, or a repelling falseness to one’s appearance.

A gentleman who has invested much time in the coif of his hair, for example, has wasted that time if the result requires him to “hold the head stiff for fear of disarranging one’s locks” (I.27).

This of course applies no less to women, who are by nature more “eager to be — and when they cannot be, at least to seem — beautiful” (I.40). A woman who eschews makeup and other artifice, Castiglione asserts, commands infinitely more grace than she who relies excessively upon it:

“Do you not see how much more grace a lady has who paints (if at all) so sparingly and so little, that whoever sees her is in doubt whether she be painted or not; than another lady so plastered that she seems to have put a mask upon her face and dares not laugh for fear of cracking it…?”

Baldassare Castiglione, The Book of the Courtier, I.27

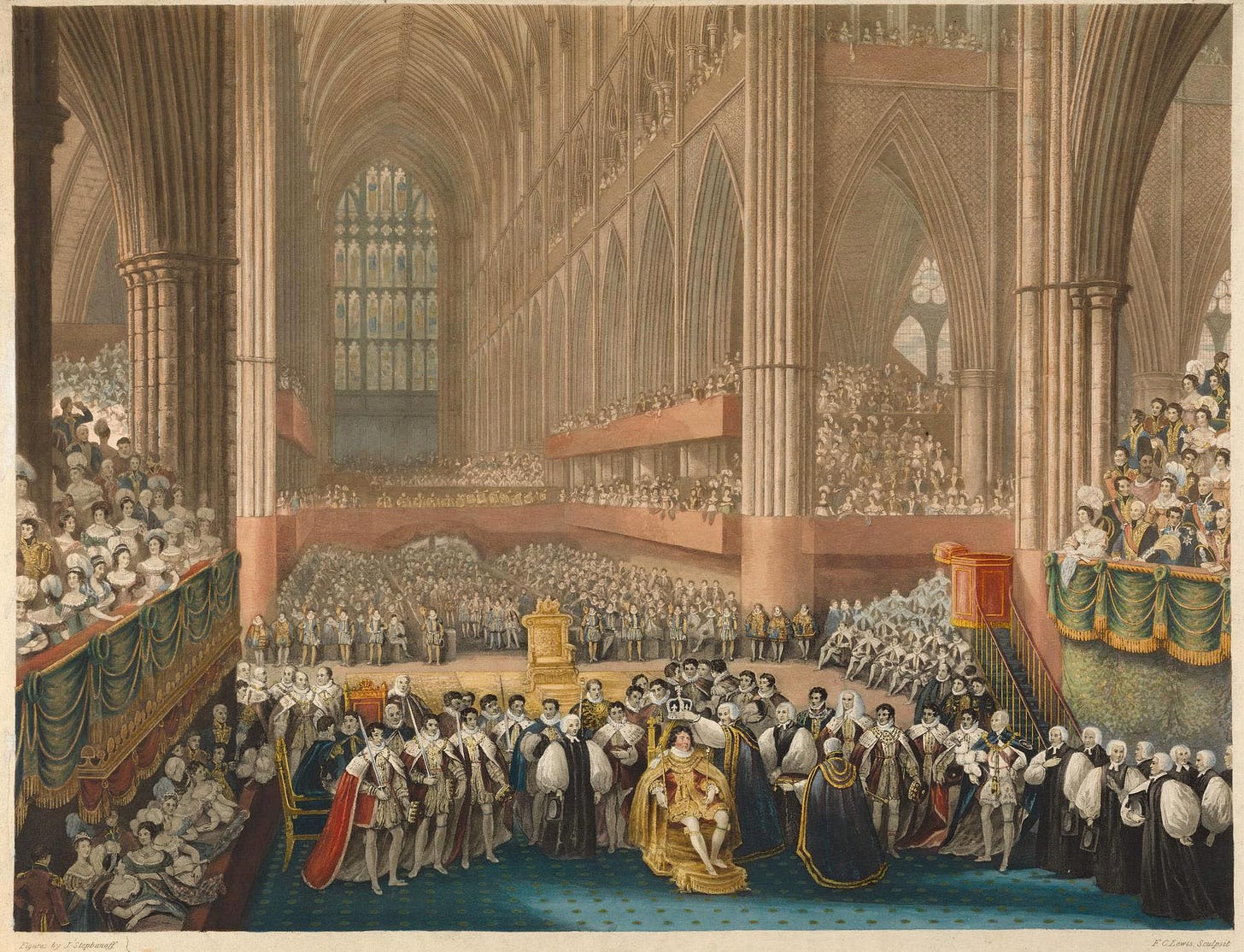

This then returns us to the matter of occasion. Extravagant dress is not in and of itself repelling if the occasion itself is extravagant. A king, after all, wears his cumbersome robes of state only to occasions of state, where ceremony and pageantry is as vital a means of communication as the spoken word, and by doing so exalts both the state and the institution of monarchy that he is representing.

This combination of attire and occasion ‘works’, however, because the impracticality of the robes is mitigated by the fact that ceremonies are generally static, or consist only of sombre and gentle movements.

Were the king, however, to dress for the ballroom or for dinner as if they were his coronation, the image of grace and indeed majesty would dissipate the instant that this incompatibility was made plain — be it in tripping on one’s garments, or knocking over a glass with an unruly sleeve at the table.

“But to say what I think is important in attire, I wish that our Courtier may be neat and dainty throughout his dress, and have a certain air of modest elegance, yet not of a womanish or vain style. Nor would I have him more careful of one thing than of another, like many we see who take such pains with their hair that they forget the rest; others devote themselves to their teeth, others to their beard, others to their boots, others to their bonnets, others to their coifs; and the result is that these few details of elegance seem borrowed by them, while all the rest, being very tasteless, is recognised as their own”

Baldassare Castiglione, The Book of the Courtier, II.27

To deviate in appearance from the expected normal, therefore, is a high stakes gamble. Quite apart from the appropriacy of occasion, if one element of appearance has been plainly neglected, it does not matter how much attention was lavished on the others — the whole is compromised by that distraction, a phenomenon encapsulated by “once you see it, you can’t unsee it”.

‘Dressing to impress’ implies deception, and Man instinctively reacts negatively to the revelation that he has been deceived. Thus a ‘gap’ in appearance, be it in a neglected detail or in a discrepancy between the ornament of dress and how at ease the wearer looks while donning it, opens up the deception and reveals it to be artificial, guaranteeing a sour impression.

If you are going ‘all in’ on your ‘look’, therefore, it will backfire spectacularly unless all components are in agreement, with each other, with the occasion and with your own nature:

“Therefore it will be well to speak of our Courtier’s clothes; which I think, provided they be not out of the common or inappropriate to his profession, may do very well in other respects if only they satisfy him who wears them”

Baldassare Castiglione, the Book of the Courtier, II.27

Yet clothing is about more than impressions at individual occasions. It is also about your most basic sense of belonging…

Clothes Anchor Culture

When considering almost any form of media, from television and film to art across the centuries, there is one foolproof method of determining which historical setting it belongs to, or is trying to evoke — look at the clothing.

If the men are wearing neckties, the depiction cannot predate the late 19th century. If they wear a cravat, the 17th. If the men are predominantly wearing brimless caps, it is unlikely to be later than the 15th century. Likewise, if the men are wearing wigs, it is the 17th century if the wig is long, and the 18th if it is short.

Rather like architecture, until the spread of globalism fashion was a natural outgrowth of native culture, and a representation of it. Few peoples, however, placed greater stock in this than the Romans, for whom clothing distinguished between civilisation and barbarism. If a man in classical sculpture is wearing trousers, he is uncivilised, whereas the Romans themselves, as Virgil famously defined them in the epic poetry of The Aeneid, were “masters of the world, and people of the toga” (Aeneid I.282).

It was a passage enthusiastically quoted by the Emperor Augustus himself, who as part of his moral and sumptuary reforms, banned inappropriate clothing in the Forum, directing the aediles to turn away all those not wearing the toga (Suetonius, Life of Augustus, 40).

Fifteen centuries later, Castiglione echoed this sentiment, lamenting the growing influence of foreign trends in fashion. “But I do not know by what fate it happens that Italy has not, as it was wont to have, a costume that should be recognised as Italian”, he remarks, criticising the erosion of identity that this was causing.

Adopting foreign clothing for the sake of ‘making a statement’, he implies, is itself a dangerous form of affectation.

Any aesthetic adopted in a context where it lacks roots is, after all, by definition superficial, and the result is invariably ‘tacky’. If perpetuated over time, however, the actual roots of said culture begin to corrode. Castiglione here produces the poetic example of the Persian Emperor Darius, who chose to discard an Iranian blade in favour of wearing a Macedonian sword, a move interpreted by his kin as an implicit surrender to Macedonian supremacy — a fear borne out by Alexander the Great’s actual conquest of Persia which commenced just a year later (II.25).

Such history threatened to repeat itself in Italy, Castiglione feared:

“So our having changed our Italian garb for that of strangers seems to signify that all those for whose garb we have exchanged our own must come to conquer us: which has been but too true, for there is now left no nation that has not made us its prey: so that little more is left to prey upon, and yet they do not cease preying upon us”

Baldassare Castiglione, The Book of the Courtier, II.26

His suspicions were far from ungrounded. For Castiglione’s own lifespan coincided with the outbreak and escalation of the Italian Wars, a bloody sixty years of intermittent conflict by which the Italian states were indeed subjugated by foreign powers, a process the Italians themselves, he sustained, were subconsciously or not legitimising by their dress choices.

Dress speaks not merely to the man, therefore, but to the culture he admires and wishes to see thrive…

Dress as the Stage

To the aristocratic mind, dress is the stage from which the gentleman performs life.

This is not to say that it should be considered the centrepiece of who you are, any more than an envelope is more important than the letter within. Dress is not a substitute for character, but it does serve as a channel to it. Well chosen words are of scant value if nobody has already decided to lend you their attention.

Unwarranted extravagance in clothing demeans a man, but so too does performative or careless austerity. To dress with grace is to enhance the power of your presence and words, and to dress without it is to undermine that power. Being faced with so many examples of the latter today should not deceive a man into losing belief in the former, and denying the truth that dress does, indeed, matter.

Upon this point Count Baldassare Castiglione makes one final appeal to us, urging us to reject inelegance:

“And this kind of dress I would have our Courtier shun, by my advice; adding also that he ought to consider how he wishes to seem and of what sort he wishes to be esteemed, and to dress accordingly and contrive that his attire shall aid him to be so regarded even by those who neither hear him speak nor witness any act of his”

Baldassare Castiglione, The Book of the Courtier, II.27

Lovely essay. I have always admired Castiglione's concept of sprezzatura. I've restacked the whole post as well as several excerpts.

By the way, I couldn't help but think of this quote re yesterday's show-and-tell by Trump of his MAGA hats to Macron and Zelensky:

“The fool adorns himself, and the elegant man gets dressed”

-Honoré de Balzac, Treatise on Elegant Living

Your exploration of Castiglione's sprezzatura beautifully captures something deeply biblical. That "outward things often give knowledge of those within."

It reminds me of how the elaborate priestly garments in the Old Testament weren't vanity, but sacred function. They reflected the cosmic order and the priest's role. The biblical tradition supports your point that dismissing appearance entirely is an overcorrection (for normal people). Though many see it as spiritual and pure.

We're called to be good stewards of how we present ourselves, not out of pride, but out of respect for the occasions and people we encounter.

What strikes me most is how sprezzatura mirrors the biblical concept of grace itself, making the profound appear natural, and the sacred accessible. The parable of the wedding garment suggests there's a proper way to "dress" for the occasions life presents us, and choosing to ignore this isn't humility but a kind of carelessness toward others and the moment itself.