How (Not) to Ruin Everything

The 3 mistakes that cost a man his kingdom...

It is the curse of Man that what is hard won is easily lost. Italy is a land that knows this harsh truth better than any.

In the 15th century, the peninsula was the beating heart of the Western world, and the nerve centre of the European Renaissance. Yet within a few short decades, she was but a distant vein, eclipsed by the monoliths of France, Spain and England. How was so mighty and swift a fall possible?

To Niccolò Machiavelli, the man today revered as the champion of ruthless pragmatism, this was no million dollar question. For the Florentine thinker and statesman, the answer was clear — it was the decision of one man, and one man alone, that had “ruined Italy, and continued to keep her in desolation” (Machiavelli, Florentine Histories VIII).

That man was Ludovico Sforza, the usurper of Milan and primary employer of Leonardo da Vinci, whose fatal decision in 1494 not only backfired spectacularly upon himself and his family, but also destroyed the sovereignty of Italy, reducing her states to mere spoils for other powers to fight over.

Ludovico came so close to greatness, only to bring it all crashing down. Today, we explore the three critical mistakes he made, so you can avoid the same fate…

What Could Have Been

It is in no small way ironic that the man widely condemned as the cause of Renaissance Italy’s downfall had also been the typical example of a Renaissance Italian ruler.

Milan, like many of the northern Italian states, had endured a turbulent 15th century, characterised by violent political struggles. An ill-advised and ill-fated attempt to force a republic upon the city had thrown the Duchy of Milan into prolonged chaos, from which the Sforza family, and ultimately Ludovico in particular, finally emerged victorious.

There was a complication, however. When Galeazzo Maria Sforza was assassinated in 1476 by republican conspirators, the Milanese succession passed to his son Gian Galeazzo. Since the new Duke was just seven years of age, the regency was soon assumed by his uncle, Ludovico. Yet over the eighteen years which followed, Ludovico became accustomed to government, and increasingly convinced that the sickly Gian Galeazzo was unfit for rule — a conviction spurred by the the latter’s apparent lack of interest.

Whispers began to spread that the Duke’s uncle was usurping the crown.

It is to Ludovico’s credit, however, that he largely responded to this in the best possible way: by governing well. Few other princes of Italy invested in their own realm on quite the scale of Ludovico Sforza, and under his reign the Duchy of Milan was second only to the Republic of Venice as the wealthiest state in Italy. Canals were dug, cities beautified, churches built, artists patronised and industries incentivised, from the cultivation of rice to silk. His most disgruntled subjects may have resented the taxes that he raised, yet this was rather mitigated by it being obvious where the money was going.

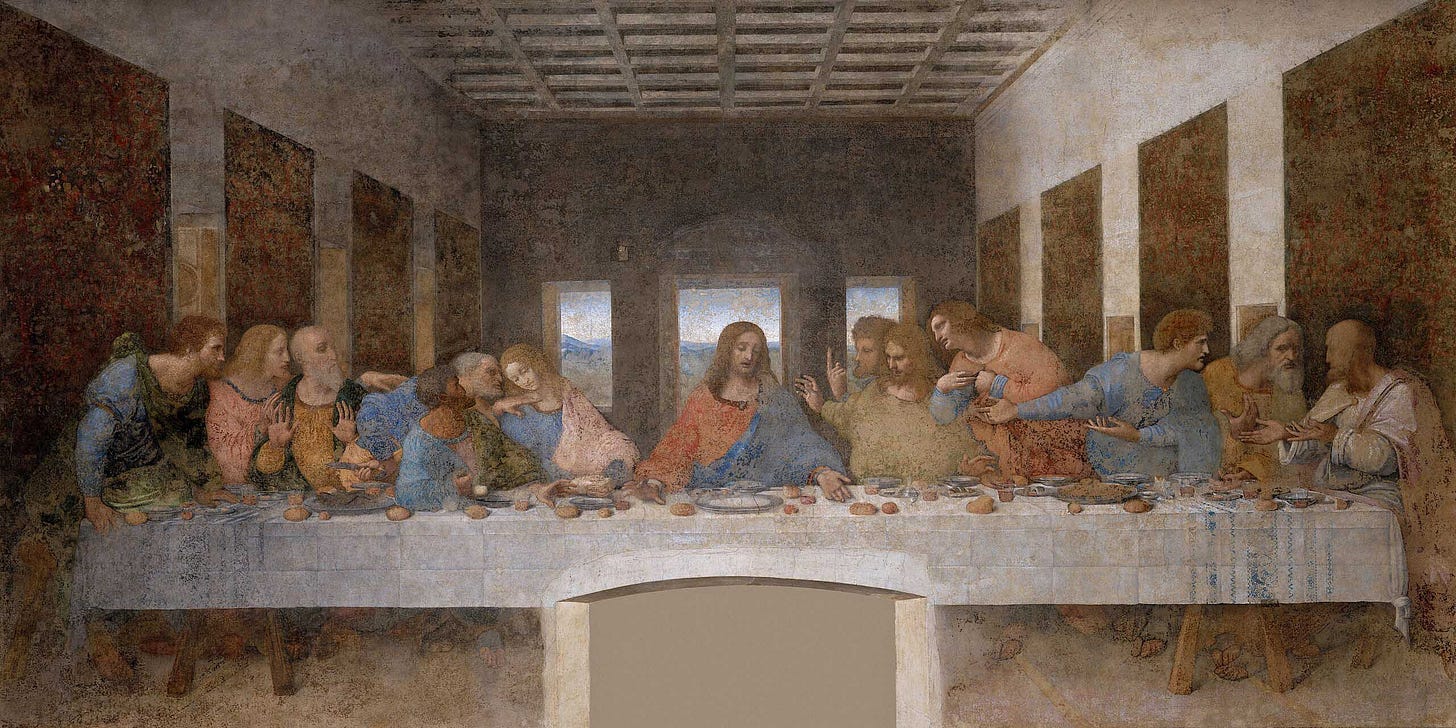

But most famously of all, it is to Ludovico Sforza that none other than Leonardo da Vinci owes much of his success. For while his youth in Florence had established him as a respected painter, what truly transformed Leonardo into a living legend were his seventeen years in Milan, whose ruler was his foremost client. It was Ludovico’s patronage, after all, that allowed Leonardo to pursue his dazzling array of interests from engineering to anatomy. It was indeed the regent, too, who around 1494 commissioned Leonardo to paint the now world-famous Last Supper.

Well educated in both intellectual and physical pursuits, Sforza also possessed a charisma that could be disarming. An imposing man with a swarthy complexion, he was famously nicknamed il Moro — ‘The Moor’ — but far from being offended, Ludovico embraced it, seeing a certain exotic quality to it that evoked old chivalric legends.

Unfortunately, all of this was thrown away by three all too common human mistakes, that have destroyed everything from friendships to businesses and empires. Let us now analyse what they were, so you can hopefully avoid repeating them…

Mistake #1: Allowing the Heart to Rule the Head

As a ruler who lacked the legitimate right of his nephew, Ludovico faced the same problem as any usurper. With the legal order transgressed, support for him was entirely contingent on him delivering results, and the moment he did not, everything collapsed.

For Ludovico Sforza indeed, the seed of ruin was planted when he made the all too familiar error of subordinating his judgment to emotion, and the ground was laid for this where it so often is — the home.

In 1489, in the hopes of strengthening Milan’s position in Italy, it was arranged that Gian Galeazzo would marry Isabella of Aragon, granddaughter of the wise King Ferdinand I of Naples. This move, however, backfired spectacularly on Ludovico, for the new Duchess of Milan proved to be strong-willed, and grew increasingly vocal in her demand that the regent relinquish power to her husband. When she began to denounce his conduct in letters to her aghast Neapolitan relatives, the family feud spilled over into a diplomatic debacle.

Things escalated dramatically in 1491 when Ludovico himself made a political marriage to Isabella’s cousin, and daughter of the powerful Duke of Ferrara, Beatrice d’Este. Far from being a mediating influence, however, following an optimistic start the two cousins swiftly began to despise each other.

For her part, Beatrice disliked having to grant precedence, as the wife of the regent, to Isabella. Isabella, in turn, resented the pretentious conduct of Beatrice. The smouldering antagonism between the two wives grew so severe that there were soon two courts in Milan, as Ludovico and the government resided in the capital, while the actual Duke and Duchess were kept at arm’s length at Pavia.

One year later, with the words of a wife with whom he was utterly besotted having fuelled a newfound paranoia, Ludovico took a decision that would cost him, his family, and country, everything.

Convinced now that the Neapolitans were plotting regime change against him, aided by the scheming of Isabella, il Moro made a ‘pact with the devil’. Knowing that the French kings had a distant claim to the Neapolitan throne, inherited from the Angevin conquest two centuries earlier, he signed an alliance with King Charles VIII of France. Believing it would safeguard him from Naples and Isabella’s relatives permanently, Ludovico was content that he now had great leverage with which to deter the Neapolitans.

Little did he realise, however, that Charles saw the deal as rather more than just ‘leverage’. Indeed Ludovico had just handed France both the pretext and the means to actually pursue a claim on Naples, and launch an otherwise unthinkable invasion of Italy.

“Thus between Isabella, the Duke's wife, and Beatrice, each of them wanting to prevail over the other, both in place and in ornament, as in other things, arose such towering competition and disdain, that they would be the causes of the total ruin of their Empire”

Bernardino Corio, L’Historia di Milano

It was only a matter of time before Ludovico’s world collapsed around him. Yet in an attempt to stave off disaster, he did what almost anyone would do when faced with an acute crisis — but in doing so, he only made a bad situation worse…