Who Is the Rightful King of France?

1 crown, 3 contenders...

“Paris! Paris! Royaliste!” is not a chant you might think would be fashionable in the contemporary French capital. Yet it was precisely these words that echoed from almost a thousand marchers just last week, on the evening of the 18th January.

The image of the martyred Louis XVI borne aloft by two young ladies, with cries of “Vive le Roi!” (“Long Live the King!) and “A bas le Republique!” (“Down with the Republic!”) accompanying the flag of royal France, was a powerful one. Indeed, the scale of the march earned the disdain and shock of French journalists and statesmen alike.

Three days later, throngs gathered at the Chapelle Expiatoire to pay homage to the memory of the fallen king, on the anniversary of his unjust execution in 1793. While neither the march nor the memorial mass were new events, what cannot be denied are the ever larger crowds which accompany both each year — and crucially, the ever greater proportion of young people who attend.

The collapse in confidence in the liberal order that has ruled most of the Western world for a century has led to a significant revival of interest in what preceded it. Furthermore, with support for democracy over other forms of government having crashed to just 57% among the 18-35 age bracket, interest in monarchism is steadily translating into support.

So, in the scenario that such trends continue and reach their inevitable conclusion, who today could take up the sword of Charlemagne, and reforge the august line of the Kings of France?

To answer that question, let us first consider how that line was broken in the first place, and why as a result there is more than one candidate for the throne.

Who was the last King?

It remains surprisingly little known in much of the English speaking world that the unfortunate Louis XVI, executed 232 years ago this week, on the 21st January 1793, was not the last king to reign in France.

Following the turmoil of the Revolutionary Wars and the collapse of Napoleon’s continental empire, on the 3rd May 1814 the monarchy was restored in the person of the martyred king’s brother, the Count of Provence, as King Louis XVIII. While his sovereignty was limited by the presence of Coalition troops, and interrupted by the chaos of the Hundred Days of 1815, which saw Bonaparte briefly reoccupy the country, the King presided over a largely steady decade on the throne.

Upon his death in 1824, he was succeeded by his and Louis XVI’s younger brother, the Count of Artois, who reigned as King Charles X. Unlike his predecessor, Charles took an aggressive line against the oligarchs in Paris who the Revolution brought to power, and embarked on an extraordinarily ambitious program to roll back the militant secularism of the 1790’s, cracking down on the excesses of the Press and restoring the Church to her rightful place at the heart of the nation.

Despised by a liberal establishment that was unable to control him, in a repetition of history the King was overthrown in a coup d'état in the summer of 1830, in an event consequently remembered today as the July Revolution. The final act of Charles, on the 2nd August 1830, was to abdicate in favour of his nine year old grandson Henry, the Duke of Bordeaux and Count of Chambord.

Unfortunately however, history would once again repeat itself. For just as Louis XVI had been betrayed by his cousin, Philippe d’Orleans, so too would the former’s brother be betrayed by the latter’s son. On the 9th August, in an act of gross opportunism, the abdication arrangement of Charles was withheld by Louis Philippe d’Orléans, who in conspiracy with the Chamber of Deputies, had himself proclaimed King instead.

Thus began the rift that would define the royalists of France — the ‘Legitimists’, who supported the senior line of the House of Bourbon, and the ‘Orléanists’, who supported the House of Orléans.

It soon became clear why the rise of Louis Philippe I, the ‘Citizen King’, had been enabled, as the governance of France became dominated by the banking and industrialist classes, all while the monarchy was steadily stripped of its ceremony and grandeur. As a result, Louis Philippe, who took the revolutionary title ‘King of the French’ in place of ‘King of France’, thereby binding his position to Nationalism, alienated both monarchists and republicans alike.

In 1848, he too was forced to abdicate in favour of his own grandson, Philippe, before insurgent pressure triggered the proclamation of the Second Republic. Louis Philippe thus remains the most recent man to reign with the title of king in France.

The Accidental Republic

The Second French Republic was plagued by illegitimacy, and proved easy to manipulate, lasting just three years before another coup d'état allowed Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, nephew of Emperor Napoleon I, to remain as President of France after the expiry of his term of office, and fully restore the Bonaparte dynasty in 1852 as Emperor Napoleon III.

As with the First, however, the Second Empire drew its legitimacy from war, and the decisive defeat of the Emperor at the Battle of Sedan in 1870, amid the Franco-Prussian War, ensured the lightning disintegration of the Bonapartist cause. From these ashes arose a Third Republic, which would prove to be the most lasting yet, though by accident rather than volition.

Amid the chaos of the war (for the Republic had resolved to continue the fight against Prussia), the legislative elections of the 8th February 1871 returned a significant royalist majority, split between Legitimists and Orléanists, to the National Assembly. Yet the seizure of power in Paris by radical factions weeks later, and the establishment of a revolutionary socialist dictatorship in the capital known as the Commune — which would inspire Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in the formation of Communism — hurled the country ever closer to the brink.

As it had eighty years earlier, rural France rejected the radicalism of the cities, and the government commenced a bloody siege of Paris to restore order, all while the German Chancellor, Otto von Bismarck, relished the prospect of a France weakened in perpetuity by radical Jacobinism. For those Frenchmen who yearned for a guarantee against a doom spiral of violent radicalism, there was but one solution — the return of a king.

The Uncrowned King

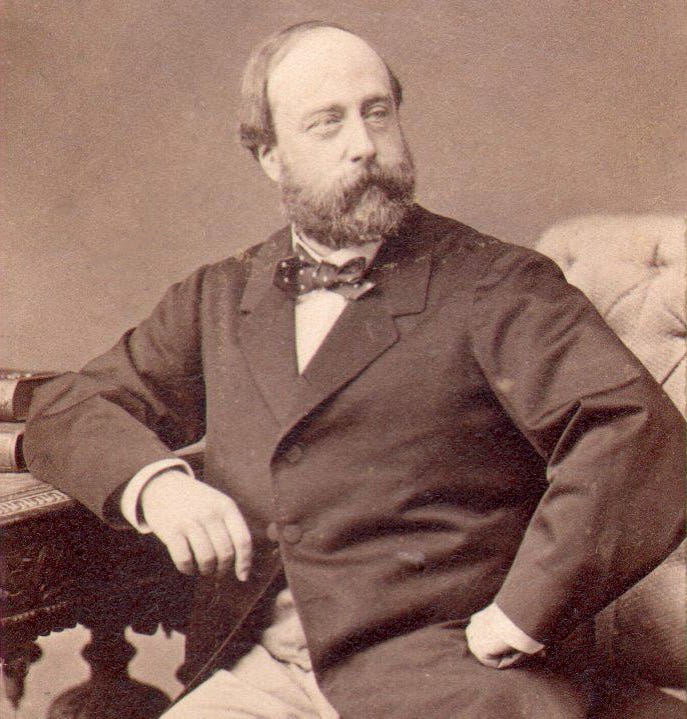

The auguries were good. Since the legitimist pretender to the throne — Henry, the Count of Chambord and grandson of King Charles X — was childless, the Orléanists supported his claim. They did so on the understanding that upon his passing, their own candidate — Philippe d’Orléans, the Count of Paris and grandson of King Louis Philippe I — would succeed him.

With a royalist majority in the National Assembly, the restoration of the monarchy was all but guaranteed. But then something happened which shocked all France.

On the 5th July 1871, the Count of Chambord issued the following proclamation:

“Frenchmen, I am ready to do anything to aid my country in rising from its ruins, and in reassuming its rank in the world.

The only sacrifice that I am not prepared to make is that of my honour. I am and wish to be in harmony with the time in which I live. I pay a sincere homage to its greatness of every kind, and whatever may have been the colour of the flag under which our soldiers marched, I have admired their heroism and rendered thanks to God for all that their bravery has added to the treasure of the glories of France.

Between you and me, there must exist no misunderstanding or suppressed thought. No, I will not be silent because ignorant or credulous people have spoken of privileges, of absolutism, of intolerance, and I know not what besides of tithes, of feudal rights — phantoms which the most audacious bad faith seeks to raise up before your eyes.

I will not allow the standard of Henry IV, of Francis I and of Joan of Arc to be torn from my handle. It is with that flag that our national unity was made. It was with that flag that your forefathers, led by mine, conquered that Alsace and Lorraine, whose fidelity will be our consolation in our misfortune.

Frenchmen, Henry V cannot abandon the white flag”

Henry, Count of Chambord, 5th July 1871

Thus did the heir of Louis XIV reject the offer of a crown. Not out of apathy to royal duty, nor impiety to God or his ancestors, but because of them. For the Count of Chambord knew that the Assembly, itself borne of Revolution, was a fickle body that would see in him what its ancestor had in his own — a puppet of party politics.

If there was to be a restoration of the monarchy, it had to be a true restoration. One in which the king reigned as the father of the nation, the steward of her faith and the sword of the church, beholden only to God and the happiness of his people, not the poison of its politics.

Often is the Count of Chambord’s rejection misunderstood as a trivial dispute over the flag. After all, the immediate attempts to convince him to change his mind failed by his refusal to accept the revolutionary tricolor as the flag of France. Yet it was not mere cloth that was repugnant to the uncrowned King, but what it represented. As long as the Assembly insisted on the symbols of godless revolution, it would only be a matter of time before it insisted on its substance.

Thus Henry, Count of Chambord, loyal to kingship not for the sake of position but for the essence of its ancient meaning, lost a throne, yet kept his honour.

Republican Ascendancy and the Wilderness of France

With a final attempt in 1873 to convince the Count of Chambord coming to naught, the defeated consensus of the Assembly, seeking to minimalise strife between the Legitimists and Orléanists, was to await his passing before offering the throne to the Count of Paris.

The window, however, had closed. By the death of Henry in 1883, the royalists had lost their majority in the Assembly, and France resigned herself to a Republic by default.

For conservative France, the lost reign of Henry V was a disaster beyond comparison, as Paris over the generations that followed conducted with patience what the revolutionaries of old had sought by violence — the de-Christianisation of France and the subordination of her spirit, and interests, to the emerging ‘international order’. In 1905, the Séparation des Églises et de l'État would formally proclaim the French Republic a secular state, and all cathedrals and parish churches property of that state. It is an arrangement still in effect today.

The Third Republic, born in 1870 from humiliation at the hands of the Prussians, would die to their successors in 1940. The Fourth, established in 1946, would survive long enough to preside over the near complete collapse of the French overseas empire, while the Fifth, ruling since 1958, has seen the sovereignty of the homeland itself methodically dismantled. In 2002, France lost her own currency.

Where, however, do the royalist causes stand in 2025 — and who are the three main contenders?