What Would Beowulf Do?

Life lessons from the heroic age...

Beowulf is one of the greatest works of English poetry ever written. And despite the occasional film adaptation or viral translation, it’s still one that few people have read all the way through.

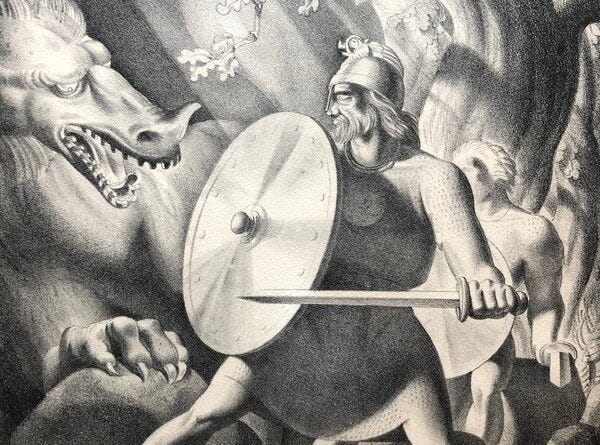

Even if you’ve only seen the film version, you’ll probably know that Beowulf is a poem written in Old English about a warrior who tears monsters limb from limb and braves dragon fire. You may also have heard that it was a major inspiration for J. R. R. Tolkien’s works.

But Beowulf also offers something you might not expect. Beyond the swords and dragons, you’ll find a coherent body of wisdom for how you should live in the world.

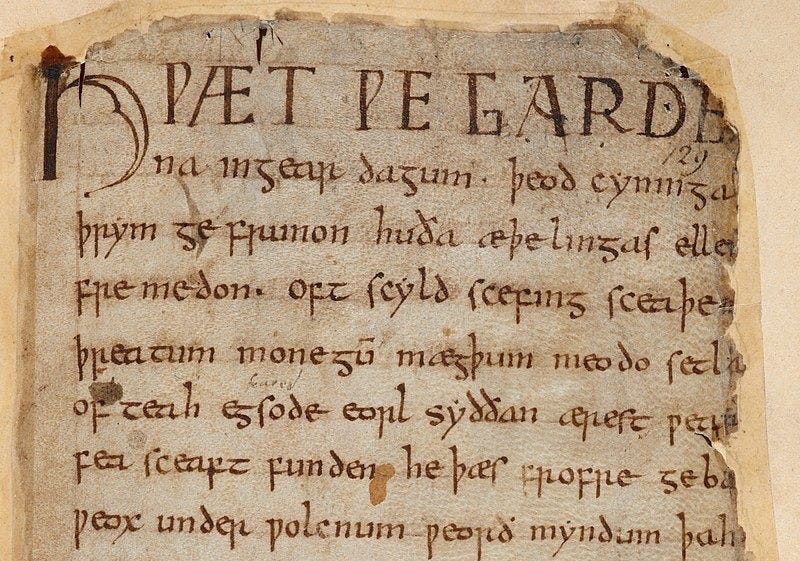

The world of Beowulf is foreign and familiar in equal measure, and this mixture of the strange and the ordinary is nowhere more evident than in the language of the poem: it’s written in something recognizable as English, yet is nevertheless incomprehensible to speakers of English today. Words like hand ‘hand’ and heofon ‘heaven’ occur on the page alongside strange fossils like frumsceaft ‘beginning’ and freoðuwebbe ‘peace-weaver.’

This is a form of English, just a very old one: we call it Old English. It’s also known as Anglo-Saxon, after the people who spoke the language.

But stranger still than the language of Beowulf is the world the poem describes. The poem takes place in an identifiable time and place: Scandinavia, just after the fall of the Western Roman Empire. But it’s also a clearly fantastic story of monster slaying, with a structure that sounds more like a folktale than a historical record.

Beowulf, a man of superhuman strength, fights first the ogre-like creature Grendel and slays him. He then defeats Grendel’s mother and, finally, a fire-breathing dragon, before succumbing to his wounds from that final fight.

But Beowulf is not just about action. The poet also wants to dispense wisdom: in fact, he’s happy to break away from the action in the middle of a tense battle scene to offer a comment on the proper way a hero should act.

If you were to follow the advice of the poem, your life might look something like the life of an aristocrat of the Germanic Iron Age, the period in Northern Europe between the 5th and 8th centuries. So what did that life look like?

It was a world in which two types of relationships ruled everything: kinship and membership in a lord’s retinue. Loyalty was owed to each.

Life in this world involved a lot of feasting, yes, and some fighting. Occasionally, both in the same evening. But the feasting and the fighting had a function. In a world where there was no higher authority than the leader of your local armed band, it was important to develop institutions to keep the peace within that band.

The feast was one of these institutions: it was an opportunity for a lord to cement and reward the loyalty of his retainers by offering food, drink, and gifts of treasure.

The narrator suggests that a young would-be lord should start this process early:

Swa sceal geong guma gode gewyrcean,

fromum feohgiftum on fæder bearme,

þæt hine on ylde eft gewunigen

wilgesiþas, þonne wig cume‘Thus should a young man bring about good

with pious gifts from his father's possessions,

so that later in life loyal comrades

will stand beside him when war comes.’(Beowulf 20–23, tr. Liuzza)

You can listen to how it sounded in Old English here:

The loyalty owed to one’s lord could come into conflict with the loyalty due to one’s family. But Beowulf is not about tragic cases of king vs. kin. For Beowulf himself, the two interests are always aligned: the young Beowulf’s lord is his uncle Hygelac, and when Beowulf becomes a lord in his own right, he is aided by his loyal kinsman Wiglaf.

When the time comes for the aged Beowulf to face his final enemy, the dragon, all his sworn retainers flee. Wiglaf alone remains. On that occasion, the narrator offers this piece of wisdom:

sibb’ æfre ne mæg

wiht onwendan þam ðe wel þenceð‘Nothing can ever

hold back kinship in a right-thinking man’(Beowulf 2600b–2601, tr. Chickering)

A close examination of the many kinslayings mentioned obliquely in Beowulf suggests that not every man is right-thinking. But that’s hardly news.

And yet Beowulf is not merely a celebration of this martial culture. It’s much more than a story of violent men getting into fights alongside their brothers in arms. There is something darker at play as well, and it’s a topic the Anglo-Saxons obsessed over.

Death will overwhelm you

You won’t get far in reading Anglo-Saxon poetry without being confronted with meditations on the impermanence of all worldly things. This is put concisely in one of the most memorable passages in another poem, The Wanderer:

Her bið feoh læne, her bið freond læne,

her bið mon læne, her bið mæg læne.

Eal þis eorþan gesteal idel weorþeð.‘Here riches are fleeting, here a friend is fleeting,

Here a man is fleeting, here a kinsman is fleeting,

And all this earthly frame becomes empty.’’(Wanderer 108–110)

The word I’ve translated here as ‘fleeting’ is læne in Old English. This is related to our word loan. That is, all the things we have in the world are on loan: our friends, our family, our wealth, and even our bodies.

This same attitude pervades Beowulf, especially as the poem progresses into its second half. The sentiment is expressed most directly in the mouth of Hrothgar, the King of the Danes. After Beowulf has accomplished his greatest triumph, the slaying not only of Grendel but also of his even more formidable mother, a grateful Hrothgar breaks off his speech of praise to issue a warning:

Nu is þines mægnes blæd

ane hwile; eft sona bið

þæt þec adl oððe ecg eafoþes getwæfeð,

oððe fyres feng, oððe flodes wylm,

oððe gripe meces, oððe gares fliht,

oððe atol yldo, oððe eagena bearhtm

forsiteð ond forsworceð; semninga bið

þæt ðec, dryhtguma, deað oferswyðeð.‘The glory of your might

is but a little while; too soon it will be

that sickness or the sword will shatter your strength,

or the grip of fire, or the surging flood,

or the cut of a sword, or the flight of a spear,

or terrible old age — or the light of your eyes

will fail and flicker out; in one fell swoop

death, o warrior, will overwhelm you.’(Beowulf 1761b–1768, tr. Liuzza)

Hrothgar, who is old and grey, was himself once young and strong. And so too will Beowulf wither and weaken with age, if he is lucky enough to survive that long. It is, after all, a dangerous world for a warrior.

This catalogue of the many causes of death is another trope of Anglo-Saxon poetry, one which appears in another poem, The Seafarer:

Adl oþþe yldo oþþe ecghete

fægum fromweardum feorh oðþringeð.‘Either sickness or age or sword-hate

will deprive the doomed departing one of life.’(Seafarer, 70–71)

Interestingly, in Hrothgar’s exhaustive enumeration of causes of death, Beowulf’s actual, eventual cause of death — the venomous bite of a dragon — is left out. I’ve often thought of this as a subtle trick played by the Beowulf poet to show that even the wisdom of age has its limits. It too is a product of this fleeting world.

I know one thing that never dies

If we left our assessment there, with a solemn meditation on the impermanence of all things and the inevitability of death, the poem — and life itself — might seem to us a rather dreary thing. But that isn’t the attitude the poet wants to leave us with; at least, it’s not the whole story.

Let’s turn to the Old Norse wisdom poem Hávamál, ‘sayings of the High One’ (referring to the god Odin). Hávamal echoses the sentiment expressed by The Wanderer in remarkably similar language. But Hávamál offers the reader a way out:

Deyr fé, deyja frændr,

deyr sjalfr it sama,

ek veit einn, at aldrei deyr:

dómr um dauðan hvern.‘Riches die, relatives die,

The self dies all the same,

I know one thing that never dies:

The reputation of every dead man.’(Hávamál 76/77, depending on edition)

The word I’ve translated as ‘reputation’ is the Old Norse dómr. This is a tricky term to translate because it can mean so many different things. It’s related to the English word doom, but it’s much broader than that.

The basic meaning of dómr is ‘judgement’ — what you deem, or what others deem you to be. It can extend to meanings like ‘terms (i.e., of an agreement)’, and, more relevant for us here, also ‘fame’ and ‘glory,’ that is, the good judgement of others.

What Hávamál tells us is that there is a type of immortality on offer for the humble human being. This is the immortality granted by fame, the one thing that never dies.

As Beowulf himself says,

Ure æghwylc sceal ende gebidan

worolde lifes; wyrce se þe mote

domes ær deaþe; þæt bið drihtguman

unlifgendum æfter selest.‘Each of us must come

to the end of his life: let him who may

win fame before death. That is the best

memorial for a man after he is gone.’(Beowulf 1386–1389, tr. Chickering)

Note the use of the word domes ‘fame’ in this passage: this is a form of dom, the Old English equivalent of the Old Norse word dómr. Beowulf tells us that, while death is granted to everyone, dom is only dealt to a select few. Most people are forgotten.

So how do you achieve dom in the world of Beowulf? Mainly through great deeds in battle. The narrator of the poem tells us as much when he breaks off his description of Beowulf’s grappling with Grendel’s mother to deliver some advice:

Swa sceal man don

þonne he æt guðe gegan þenceð

longsumne lof; na ymb his lif cearað‘So must a man,

if he thinks at battle to gain any name,

a long-living fame, care nothing for life.’(Beowulf 1534b–1536, tr. Chickering)

Here, the translator is using the English word ‘name’ to translate Old English lof, which means ‘praise’ in general, but can be used as a synonym for dom.

In fact, when Beowulf eventually dies, as all men must, he is given a eulogy by the narrator in the poem’s final lines, in which he is called manna… lofgeornost ‘the most eager for praise (lof) of men.’ In fact, lofgeornost is the very last word.

When translated into Modern English, it can sound like a strange way to end a poem: to be ‘eager for praise’ isn’t particularly positive for us. It’s meant as a compliment, but the modern ear doesn’t hear it that way. But for Beowulf, lof isn’t just praise but a form of immortality: it becomes, as Beowulf himself said, “the best memorial for a man after he is gone.”

Our lives today are certainly far from those of the fighting and feasting men of the Germanic Iron Age. But there’s something that can still speak to us in these bits of wisdom scattered throughout Beowulf. The bonds of kinship remain, as does the value of loyalty to those you’ve chosen to serve.

Great deeds may not always be rewarded by undying fame, but they’re as necessary now as they’ve ever been, despite — or because of — the fleeting nature of all worldly things.

If you’d like to keep immersing yourself in the world of Beowulf, Colin has been reading through the poem with his subscribers at the Dead Language Society. You can join in an upcoming live session or watch past recordings here.

Great post

Love this post, thank you