The Trial of King Louis XVI

The unholy consecration of the modern world order...

232 years ago this week, on the 16th January 1793, King Louis XVI addressed his people one last time from a grim scaffold in the heart of Paris:

“I die innocent of all the crimes laid to my charge; I pardon those who have occasioned my death; and I pray to God that the blood you are going to shed may never be visited on France”

Louis XVI, King of France and Navarre, his last words, 16th January 1793

With that, the guillotine fell, the doctrine of might is right prevailed, and the tyranny of arbitrary justice claimed the life of the heir of Charlemagne.

In this piece, we consider the trial that condemned this King to death, and the charges that were laid against him. It was a verdict upon which the course of history depended, and which formed the unholy consecration of the world order we know today.

We will examine the trial in the words of those who were there, both of the prosecution and of the defence, and assess the legitimacy of the charges presented.

But first, let us recount the events which led to the arrest of the King of France.

The Capital against the Country

1792 found a France bleeding in body and in spirit. Three years had passed since the National Assembly, enraged that the King’s openness to cooperation did not extend to being dictated to, had set a mob upon the Bastille.

The King had been an effective hostage of the Paris junta ever since the confinement of the Royal Family to the Tuileries Palace on the 6th October 1789. With the situation spiraling into a dreadful choice of total capitulation or civil war facing conservative France, the last of the King’s liberties were quashed on the 22nd June 1791, when a move to rendezvous with loyalist forces at Montmédy was barred by his arrest at Varennes.

Now, the King awoke daily to an ever more impossible situation. The revolutionary constitution, while preaching popular sovereignty in the provinces, had carefully reassigned power to a clique of oligarchs in the capital, to whom the monarch was nothing more than a rubber stamp to their own intentions.

Such then was the dilemma of the unfortunate Louis XVI — should he challenge the increasingly extreme edicts demanded of him in their entirety, and risk the absolute overturn of government, or concede the least belligerent of them, in the hope of stopping the most radical?

The Arrest of the King

When the junta coerced the King into approving war against Austria, the demoralised and under-equipped French armies suffered defeat after inevitable defeat. The once formidable Armeé Royale had been gutted to a political paramilitary, with up to half the officer class purged or defecting, only to be replaced by men appointed for their loyalty to the new regime over competence in the field.

As entire regiments deserted, the pressure upon the Legislative Assembly grew ever more acute, and so too their need to divert accountability. This was especially so after the entry of Prussia into the war, when the movement of the frontline ever closer to Paris saw hysteria conquer the streets of the revolutionary capital. The point of no return came on the 25th July, when in the Manifesto of the Duke of Brunswick, the Coalition demanded the safety of the Royal Family be guaranteed, and that further violence against their persons would trigger an escalation of war.

The junta, seizing upon this, declared the Manifesto evidence that the King was in league with their enemies, whipping up an unholy alliance of the most extremist militias in the capital that were as hostile to the Assembly as they were to the monarchy. Under the fiery rhetoric of Georges Danton, this ‘Insurrectionary Commune’ marched on the Tuileries on the 10th August.

Despite the express order of the King that violence should not be offered, the pandemonium that erupted on the streets around the Palace prevented the command from reaching all officers, and a fierce firefight ensued between heavily outnumbered contingents of the King’s Swiss Guard, and the insurrectionary forces.

Some six hundred Swiss Guardsmen fell in the massacre, and what little remained of moderation in the Assembly crumbled before the violence of the wings. Two days later, the King was arrested, and brought to the Temple prison. It would be his final accommodation on Earth, as he awaited the judgment of the victors.

To Try a King

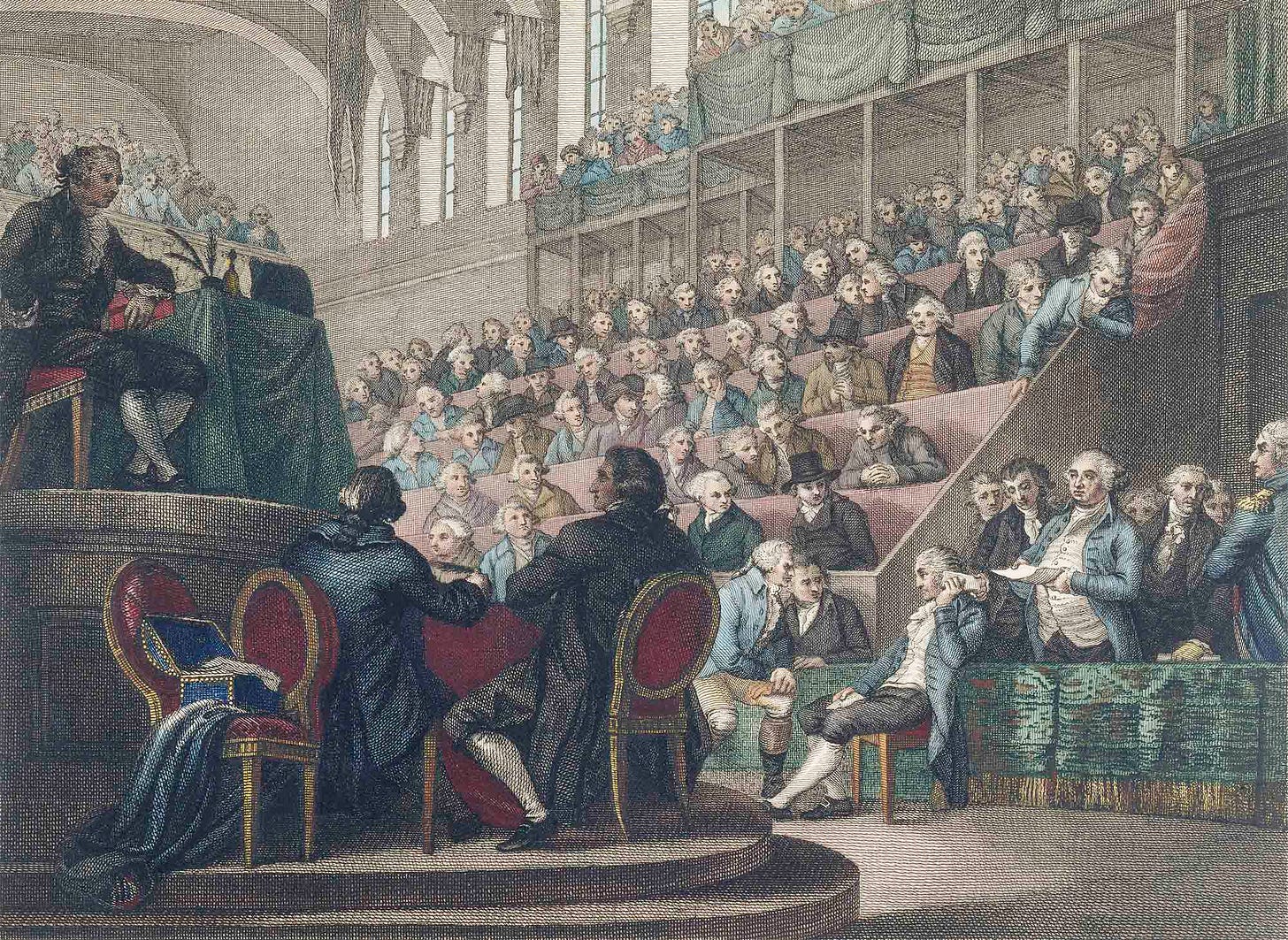

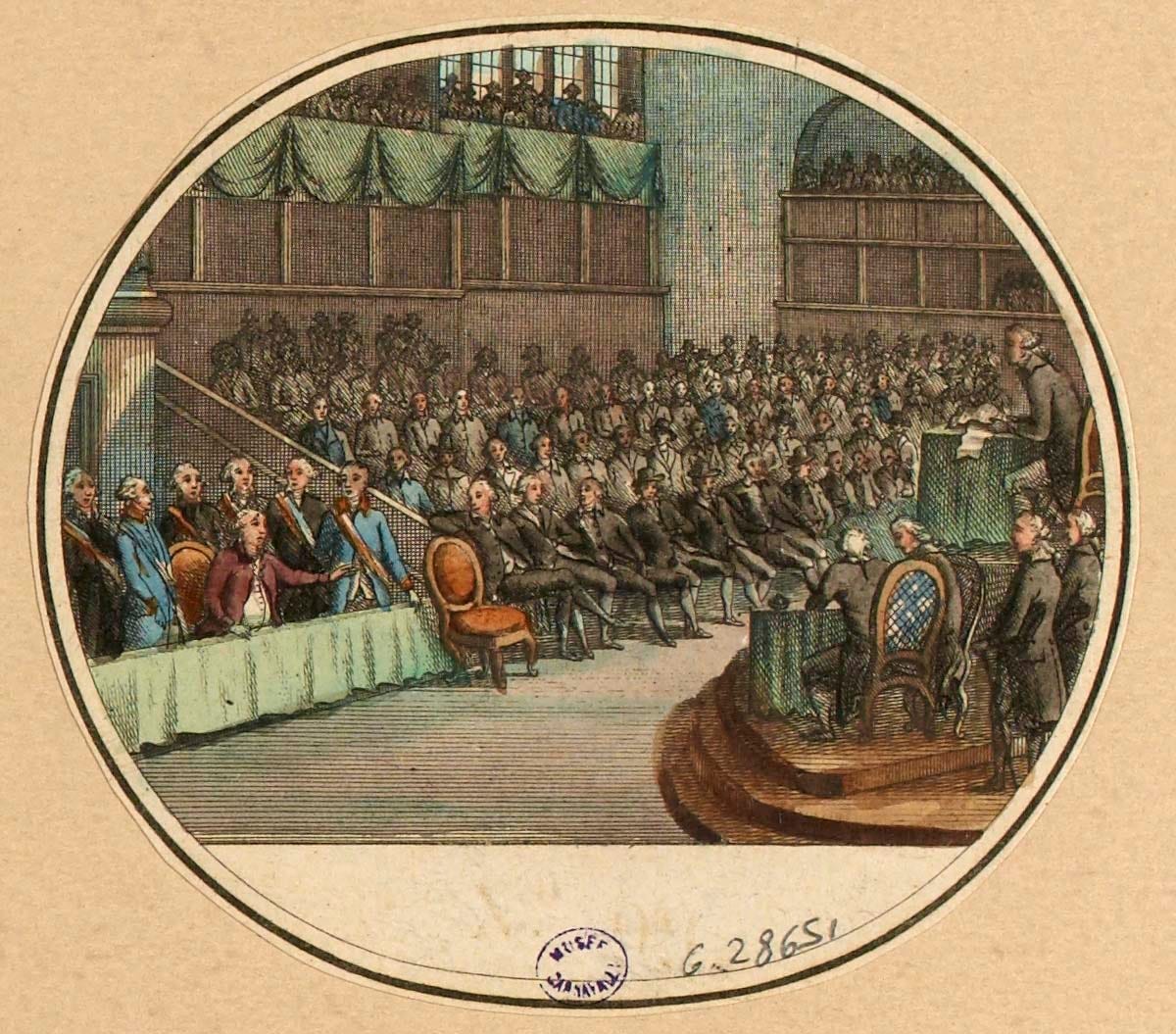

With the incarcerated King’s powers suspended, elections were called for a new government in Paris that would determine the constitutional future of France — the National Convention.

The elections, held in the first two weeks of September 1792, were characterised by abysmal turnout and widespread voter intimidation, while the proceedings in Paris were openly rigged. Any man who had been a member of the conservative Feuillant Club — which in the legislative elections just twelve months earlier had won over a million and a half votes — was stripped of the franchise, along with thousands who had signed a petition protesting the storming of the Tuileries.

As a result, the National Convention which assembled in the capital on the 20th September was entirely dominated by the most extreme forces of revolutionary Paris. Less than twenty four hours later, the Convention proclaimed the abolition of the monarchy, cleaving over a millennium of continuity in France and pulling the rug from under any lingering hopes of stability.

As the Convention set to work with the aim of eradicating all references to Christianity in the state, one great question now lay at the forefront of their wrath:

What to do with the King whose constitutional position they had all as one betrayed?

There were those, represented by the Girondist faction, who were content to keep Citoyen Louis Capet, as they now mockingly called him, as a hostage to be used as a bargaining chip in the war. Arrayed against them were the ‘Montagnards’, so named because they physically occupied the highest seats in the room, who bayed for the blood of the Bourbons.

One of the deputies from the Vendeé, Charles Morisson, condemned such belligerence, arguing that the person of the King was, as written in the 1791 Constitution, “inviolable and sacred”, and therefore could not legally be charged. Jeered at by the Parisian deputies, this proposal was nevertheless met with macabre support by the spokesman of the Montagnards, Louis Antoine de Saint-Just.

Saint-Just too argued that the King should not be tried, but only because he deemed the King unworthy of trial. “I can see no middle ground: this man must reign or die”, he declared. Robespierre, leader of the no less radical Jacobins, concurred, “Louis must die because the nation must live”.

Not yet entirely divorced from ‘optics’, however, the Convention, largely populated by lawyers, conceded that some form of trial would have to take place. A trial, however, in which the Convention itself would serve as both judge and jury. But what crimes was the King to be charged with?

The Indictment of France

By mysterious coincidence, on the 20th November it was suddenly announced that a secret iron chest had been discovered in the walls of the Tuileries. In a stroke of extraordinary convenience, said chest harboured a vast cache of documentation attesting to the King’s counter-revolutionary conduct and sympathies.

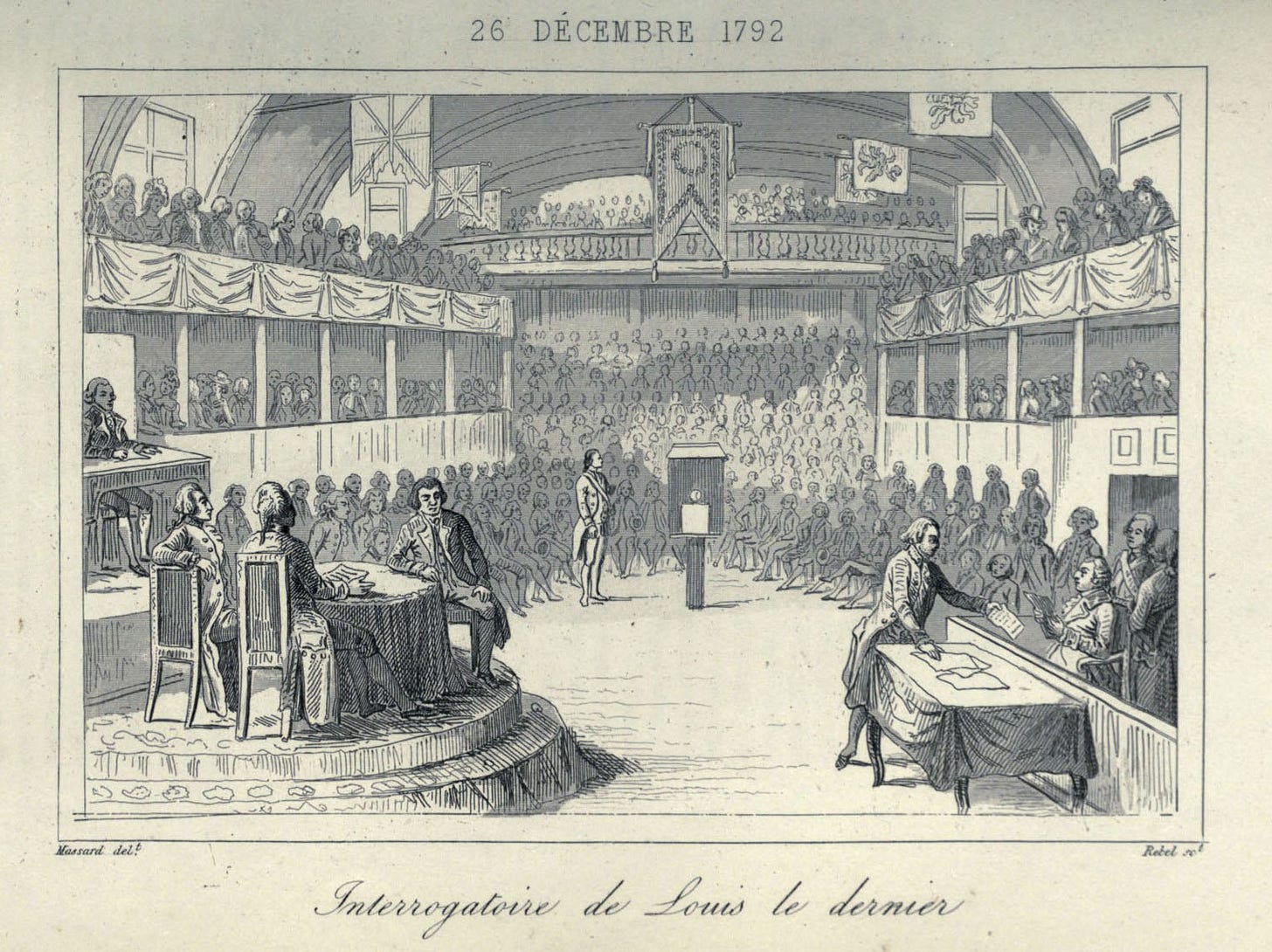

That the papers might be forgeries was a concern expressed by some of the deputies, but not enough to prevent the preparation of charges in a matter of days. Thus on the 11th December 1793, Louis XVI was summoned before the Convention.

Contempt accompanied the accused all the way to the court. ‘Guillotine!’ was shouted at him along the route, and upon his arrival, the King was made to wait three hours before admittance. Louis, bearing the ordeal with great Stoicism, merely expressed regret that he had been robbed of time with his son.

It was at this moment that Bertrand Barère, President of the National Convention, addressed the gathered representatives with fateful words:

“You are on the point of exercising the right of national justice; you made yourselves answerable to all the citizens, for the wise and firm conduct which you are to pursue on this momentous occasion.

Europe observes you; history records your thoughts and actions; incorruptible posterity will judge you with inflexible severity. Let your attitudes correspond with the new functions you are about to perform; impassivity and silence become judges; the dignity of your fitting ought to be responsible to the majesty of the French Nation; she is ready by your organ to give a great lesson to Kings, and to set an useful example for the emancipation of nations”Bertrand Barère to the National Convention, 11th December 1793

Following this with an appeal to the citizens in the tribunes, the President further undermined his duty to neutrality by assuring them that:

“The citizens of Paris will not forego this opportunity of evincing the patriotism and the public spirit with which they are animated. Let them only remember the awful silence which followed Louis, when he was brought back from Varennes — a precursory silence of the judgment of Kings by nations”

With that, the heir of Charlemagne was permitted to enter the chamber, and as he did so, clad in a yellow great coat and bathed in the serenity of one who had long since commended his Fate to the Almighty, whose judgment overrules all earthly proceedings, the heaviest of silences reigned over the hall.

Awe, fear, hatred and scorn together stilled their tongues, before the Gascon Secretary of the Convention, Jean-Baptiste Mailhe, breached it:

“Louis, the French Nation accuses you of having committed a multitude of crimes to establish your tyranny, in destroying her freedom”

Jean-Baptiste Mailhe to Louis XVI, 11th December 1793

So began the Trial of France.

“A Multitude of Crimes”

Over the course of hours, the King heard the over thirty charges brought against him. With the memory of King Charles I of England, who a century and half earlier had likewise been arraigned before a vengeful court, heavy on both sides, Louis XVI had decided to chart his own strategy.

He would not, as Charles had done, reject the legitimacy of the court out of hand, but calmly respond to the charges with clarity and economy of words. For as each charge was presented at length, often laden with extra-legal prejudice, the President concluding each with a stern “What have you to answer?”, the King seldom allowed his answer to extend beyond a single sentence. Commencing with the first of the ‘multitude of crimes’:

CHARGE: “You have, on the 20th June, 1789, attempted the sovereignty of the people, by suspending the assemblies of their representatives, and driving them with violence from the places of their fittings… What have you to answer?”

LOUIS: “There then existed no law”

Near all that was improper of the proceedings was indeed apparent from this first charge. The prosecution, being the default position of the packed court, considered the political doctrine of 1793 to command equal weight to written law, and presupposed that this applied retroactively to whenever it pleased.

The King’s response, therefore, was legally irrefutable. What’s more, it exercised considerable restraint. For when, in the summer of 1789, the Third Estate had exploited the King’s absence — an absence due to the death of his son, the heir apparent to the throne no less — to seize for itself sweeping new powers at the expense of other bodies and term itself a ‘National Assembly’, its members had grossly exceeded their mandate.

Consequently, the King had been well within his right, in both the spirit and the letter of existing law, to order the extraordinary sessions of the chamber sealed on the 20th June that year.

Yet as it began, so it continued, with charges that grew ever less criminal and ever more political. Among the most spurious of these followed soon after the first: