The Question of Greenland

The fate of Greenland may suddenly seem uncertain, but sovereignty over the world's largest island has always hung by a thread

With the second Trump administration approaching its inauguration, one of the most eccentric episodes of the first has returned with seemingly greater force — the proposal to annex Greenland, currently a territory of the Kingdom of Denmark, to the United States of America.

Whether the President-elect’s words are to be taken at face value, or form part of an elaborate negotiation strategy, remains to be seen. At the same time, we would do well to remember that a proposal to purchase Greenland is not new. Nor was it in 2019, the first time that President Trump broached the issue publicly. Indeed a succession of administrations have tried the same on multiple occasions since at least 1867.

Yet even when entirely excluding the interests of Washington, the matter of who the legitimate ruler of Greenland is has been one of the most tortured geopolitical questions of the last millennium, and one that has almost entirely escaped the peripheral vision of even many Europeans.

So what happened on the world’s largest island that brought us to this?

Who were the first Greenlanders?

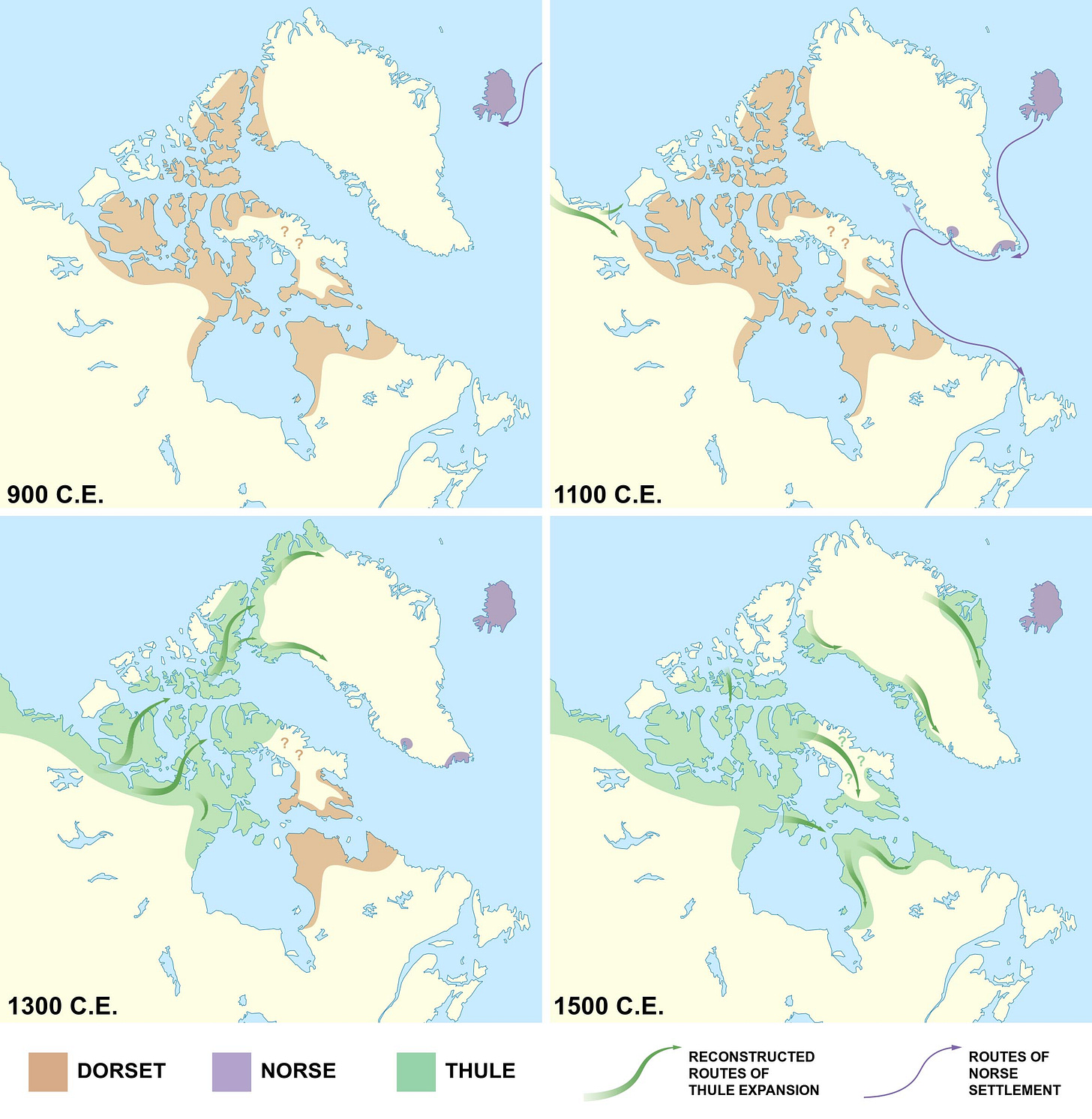

The settlement of Greenland is not defined by a single event, and even less so a single people. Instead, successive waves of peoples have migrated to the island throughout history, beginning with various cultures of the Inuit, who sporadically crossed the islands of the Canadian Arctic between roughly 2500 BC and AD 1200.

This process was not cumulative. When the so-called ‘Dorset I’ culture died out in the last century BC, Greenland was likely uninhabited by man for as many as seven hundred years before the arrival of ‘Dorset II’ in the 8th century AD.

Intriguingly, the first arrival of Europeans did not follow that of the Inuit cultures, but was concurrent with it, and from at least one concrete perspective, preceded it. After all, the ‘Thule’ people — the ancestors of today’s Greenlandic Inuit — did not make landfall upon the island until as late as AD 1100, over a century after the coming of the Norsemen.

Erik the Red & Norse Greenland

A complicated succession of criminality would ultimately bear the Norse to Greenlandic shores. At a certain point after AD 950, one Thorvald, son of Asvald, was exiled from the lowlands of Norway. The cause of this, according to the medieval Eiríks saga rauða, was “manslaughters”, though little more is known.

Thus Thorvald settled on the Hornstrandir peninsula of Iceland, where he raised his son, Erik, later called ‘The Red’ on account of his brazen beard. Like father, however, like son, for Erik would himself be exiled from Iceland around the year AD 980. In this case, we know rather more. Apparently, the thralls (servants) of Erik unleashed a landslide upon the estate of a certain Valthjof, triggering a bloody reprisal that left many dead. Erik, held ultimately responsible for this and in particular the murder of Eyjolf the Foul and Hrafn the Dueller, was promptly banished.

Heading West, Erik arrived on Greenland in AD 982, and it is this event which is formally recorded as the foundation of Western civilisation on the island. It is indeed to Erik the Red that we owe the curious name of this island. Amusingly, no elaborate mythology was crafted around it. On the contrary, the Icelandic Saga is endearingly honest about it:

“In the summer Eirik went to live in the land which he had discovered, and which he called Greenland, "Because," said he, "men will desire much the more to go there if the land has a good name"

Eiríks saga rauða, Chapter II

Thus was cynical marketing the motive for the naming of the world’s largest island.

Erik indeed proved an able salesman, and found willing colonists among his brethren, though in numbers reduced by the fickle seas to fourteen ships. The settlement they would found on the southern tip of Greenland, unimaginatively and somewhat misleadingly remembered as the ‘Eastern Settlement’, would eventually grow to several thousands in strength.

The early years of Norse Greenland appeared promising, though perhaps due more to Erik’s legend than hard reality. Two other settlements would appear to the north and west, though on a substantially smaller scale.

Abandonment

While Erik the Red remained fiercely devoted to the pagan gods, to his dismay his son Leif, following time spent at the court of King Olaf I of Norway, would take the cross.

It was indeed while undertaking a mission to convert Greenland to Christianity that Leif ‘Erikson’ — i.e. the son of Erik — was driven by the winds to the shores of North America, five centuries before Christopher Columbus sailed the ocean blue. Despite this distraction of profound historical significance, Leif returned to Greenland, succeeded his father as her petty lord, and oversaw the rapid Christianisation of the island.

Yet Greenland would prove to be a hostile paradise. Contact with the Skrælings, as they called the Inuit, was unpredictable and often violent. The vast pastures required for livestock left her population largely scattered and isolated, while the chronic lack of both iron and, crucially, wood — for few trees dot the frozen landscape — ensured the Greenlandic Norse were dangerously dependent on imports.

The omens were ill, and in 1341, the Norwegian cleric Ivar Bardarson arrived to a scene worthy of the cinema of horror. For he found naught but silence in the Western Settlement, and her farms abandoned. It is ironic that by the life of Christopher Columbus, only the ghosts of the Norsemen inhabited Greenland.

The truth of this calamity, which permanently stunted the development of Greenland, remains a mystery to this day. It is possible that the plunging temperatures of the ‘Little Ice Age’ made life unbearable for the settlers, while the devastation of the motherland by the Black Death all but severed the critical lifeline between the island and the Norse Crown.

Resurrection

For over two hundred years, the fate of the Norsemen of Greenland remained an eery mystery to the Europeans. In the meantime, as the remnants of the Erikson enterprise were weathered away by the harsh climate, the Thule Inuit steadily emerged from their northern enclaves to populate the West and South.

While the landmass was likely sighted by European whalers, and her coastline was known to cartographers, the interior lay undisturbed for hundreds of years. Fleeting attempts by Portugal and Denmark to claim it were mounted, only to be halted by the impenetrably frozen seas.

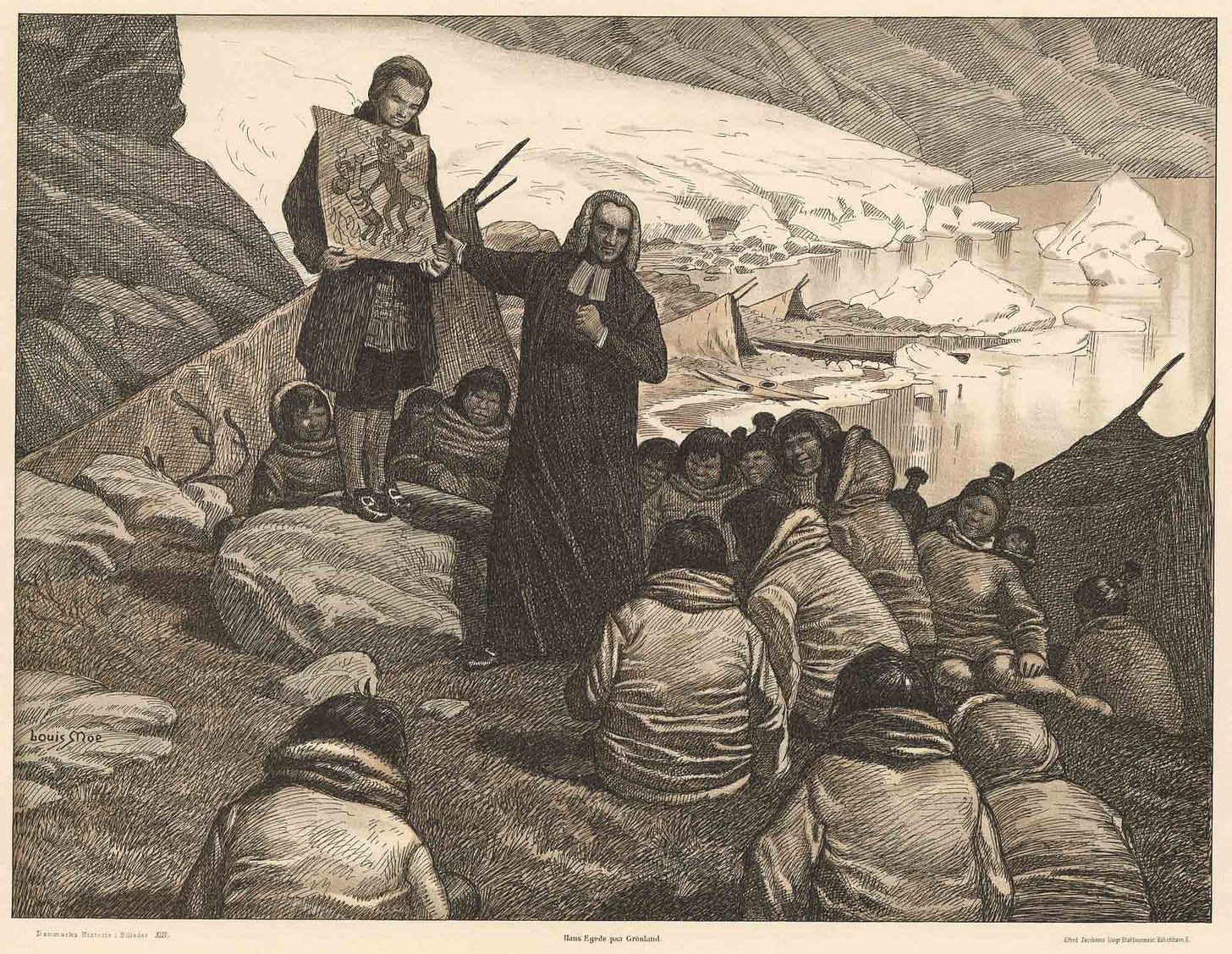

Yet the Scandinavians never forgot their Atlantic flank, such that in 1721 one Hans Egede, a pastor born in a Norway now in union with Denmark, received the blessing of King Frederick IV to try and resurrect it. In a feat directed as much by Christian faith as commercial concern, Egede succeeded in establishing a lasting presence on Greenland, reinforced in 1728 with the permanent settlement of Godthåb (the island’s capital today) and the arrival of Moravian missionaries.

While Egede had set out to locate the lost Norsemen of old, and convert the presumed still Catholic settlers to Lutheranism, when the tragedy of centuries earlier became apparent, this mission was revised to the evangelisation of the Inuit.