The Manual for Kings & Men

In 1599, King James VI of Scotland wrote an extraordinary letter to his son. In it are powerful lessons on rulership, and on life…

On this day, the 19th June 1566, the man who would unite the thrones of Scotland, England and Ireland was born at Edinburgh castle.

Yet steering the union of realms which had for centuries been bitter foes was just one of the many historic achievements of King James. It was, after all, under his monarchy that England first settled the Americas with the city that bore his name, Jamestown, in 1607. Four years later, he would oversee the most famous translation of the Bible into English, indeed giving us the King James Bible.

At the same time, one of the deadliest conflicts in world history — the Thirty Years’ War — has no position in the cultural memory of the English-speaking peoples, for the simple reason that King James was one of the only monarchs in Europe who succeeded in keeping his realms out of it. Under the first Stuart king of all Britain, the Jacobean age of Shakespeare, Ben Jonson and Francis Bacon flourished.

But the era also saw another formidable writer and thinker — the King himself. For in 1598, King James wrote the first piece of English prose to be widely translated across Europe. It was not a play or a novel, however, but a letter to his young son, Prince Henry Frederick. In this letter, he advised his heir on how, when the time came, to be a good king.

Today, we explore what the Basilikon Doron, or ‘Kingly Gift’, can teach us about good leadership, and good living, for kings and indeed all men…

The Renaissance and the Raising of Kings

While the Renaissance that blossomed out from Italy is often associated with painting, sculpture and architecture, the civilisational rebirth it actually entailed was far grander in scope than merely visual arts.

The courts of Italian and later European princes, picking up where the writings of Ancient Greece and Rome had left off a millennium earlier, began to discuss again matters as fundamental as the nature of human governance. Unlike the pagan philosophers of the past however, this would now occur through a Christian lens, as the Renaissance men and their patrons debated how government might best reflect and enable the teachings and beliefs of Christianity.

As the most deeply rooted and by far the most prevalent form of governance in the West, monarchy above all lay at the heart of such thinking. Yet while monarchy itself, divinely sanctioned and in communion with the Church, was exalted as the earthly echo of the celestial hierarchy, it was well understood that men are fallible, and thus kings are too. Consequently, the subject of the proper education of princes came to the fore, and how the curriculum might guarantee the highest chances of producing a virtuous ruler.

Slowly, but surely, this thinking spread from Italy, to the great courts of France, Castille, the Empire, England and distant Scotland. By the late 16th century, on both sides of the Protestant Reformation, it was common for monarchs to invest substantially in the education of their heirs, competing for the foremost minds to tutor them. Everyone, after all, aspired to the example of Philip II of Macedon, who almost two thousand years earlier had employed Aristotle himself to teach the young Alexander the Great.

The future King James was born into this new world, where an intimate knowledge of Latin, and to a lesser extent Greek, along with a ready familiarity with the classical texts, was considered an essential qualification of a ruler.

The formative years of James’s own life were a tale of both profound tragedy and great illumination. He was just months old when his father, Henry Stuart the Lord Darnley, was murdered by a still today unknown assailant. Shortly afterwards his mother, the famed Mary Queen of Scots, was forced to abdicate by her rebellious nobles, and following her implication in a plot against Queen Elizabeth I of England, was executed in 1587, to the terrible anguish of her twenty year-old-son.

Only the diligence of his tutors, particularly George Buchanan, steadied the education of the now King James VI of Scotland, whose rigorous program and efforts to ensure the library was well stocked succeeded in fostering a great love of learning in the monarch, and a desire to encourage the same among his subjects. It was also an education which gave James the baseline of knowledge, the confidence and curiosity to write his own works as well as read those of others.

Following his marriage to Anne of Denmark in 1589, fatherhood would focus this passion, particularly after the birth of his first son, Prince Henry, five years later.

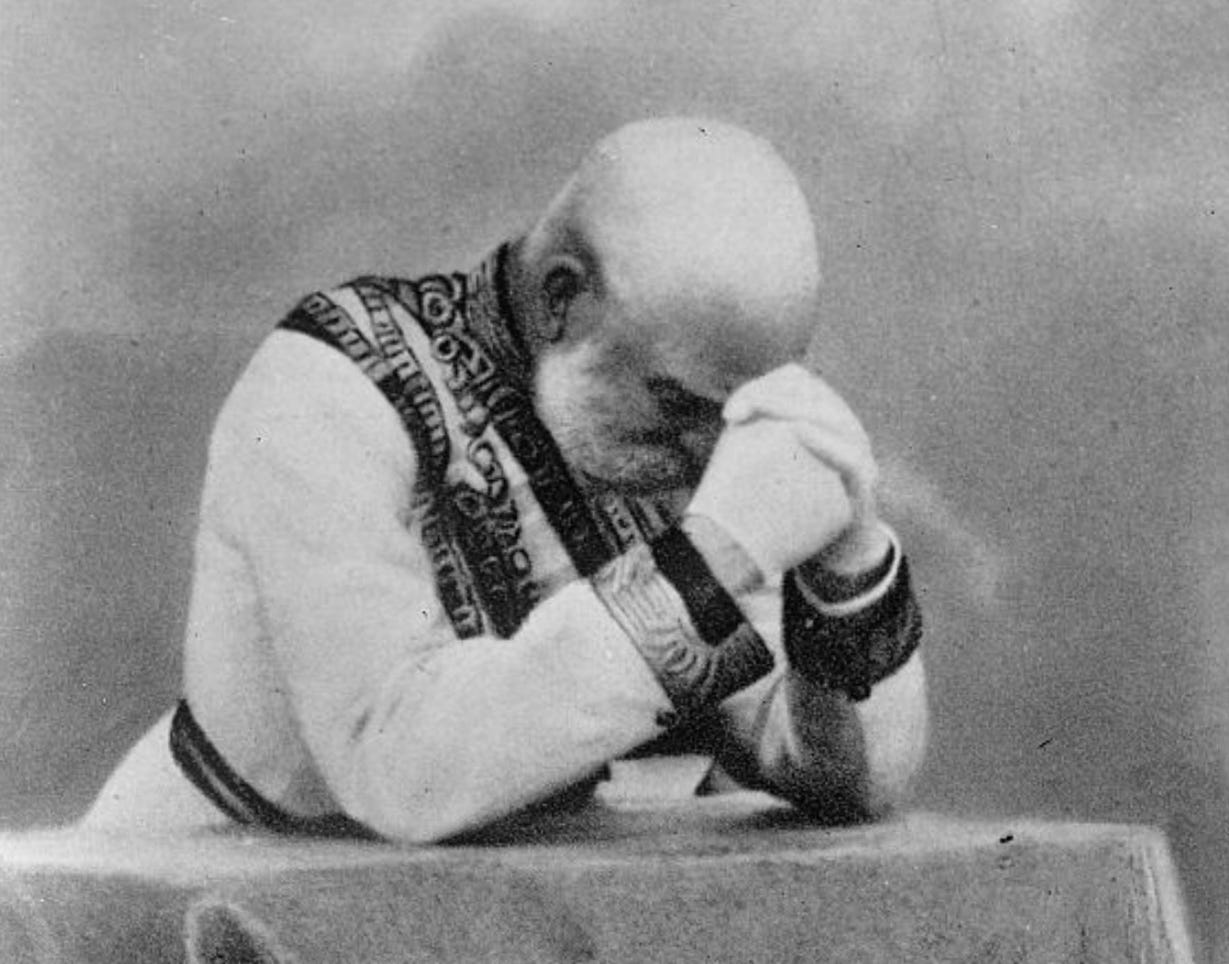

This inspiration would bear fruit in 1598, when the thirty two year old King James, having just written The True Law of Free Monarchies, and perhaps conscious of his own mortality, and the very real possibility that he, like his father before him, may not live to raise his own son, wrote a letter he hoped the four year old Henry might one day read and absorb — the Basilikon Doron…

On Fatherhood

“To Henry, my dearest son and natural successor”, the King begins, “to whom can this book of instructions so rightly pertain, but to a Prince in all points of his calling, and so too a Christian towards God, as much as a King towards his people?”.

The dedication of the Basilikon Doron itself is a passage as powerful as it is personal, and a touching reminder of the burden of fatherhood. For the King lays out the need for this letter thus:

“Since I the author thereof, as your natural Father must be careful for your godly and virtuous education, as my eldest Son and the first fruits of God’s blessing towards me in posterity”

King James VI & I, Basilikon Doron, Dedication

All fathers, indeed, must never lose sight of their central calling. That in their sons are their joy, but so too their legacy. At their birth is planted a seed, and should the gardener neglect its germination and growth, the garden will wither. Should he instead tend to it, the garden will bloom, and its beauty endure.

King James, however, while blessed with a talent for words, did not intend for the Basilikon Doron to be a dense philosophical treatise. Rather, he sought to leave his son a practical manual, which he divided into three sections:

“The first teacheth you your duty towards God as a Christian: The next your duty in your office as a King: And the third teacheth you how to behave yourself in different things, which of themselves are neither right nor wrong, but according as they are rightly or wrong used: & yet will serve, according to your behaviour therein, to augment or impair your fame and authority at the hands of your people”

King James VI & I, Basilikon Doron, Dedication

Let us explore the King’s extraordinary advice in each of these three fields…

On Duty to God

“He cannot be thought worthy to rule and command others, who cannot rule and subdue his own proper affections and unreasonable appetites, nor can he be thought worthy to govern a Christian people, knowing and fearing God, if he in his own person and heart, feareth not and loveth not the Divine Majesty”

King James VI & I, Basilikon Doron, Book I

A king, therefore, can expect no virtue of his own people that he does not practise himself. Should there be disconnect between the faith of the governed and the governor, only strife will result.

The Divine Right of Kings, a concept that is strongly associated with King James and the Stuart dynasty he headed, is in the post English Civil War world frequently presented in bad faith as the notion that ‘the king can do whatever he wants’. In reality, ‘Right’ in this context is better understood in the English of our own times as ‘Responsibility’. That the king is responsible above all to the divine, that being God.

The king is not, and indeed cannot, be beholden to anyone but God. To be beholden to any man or man-made mechanism is to be beholden to the fallible, paving the way for the vices of the king and the vices of corruptible men to encourage and enhance each other. The responsible king, as the responsible man, must be wary at all times of malign influence, never losing sight of the truth that only God is perfect, and while men may judge others in life, it is ultimately God who judges both kings and men in eternity.

King James develops this with the other side of the ‘Divine Right’:

“Think not therefore, that the highness of your dignity diminisheth your faults, much less giveth you a licence to sin, but by the contrary your fault shall be aggravated, according to the height of your dignity; any sin that ye commit, not being a single sin procuring but the fall of one; but being an exemplar sin, and therefore drawing with it the whole multitude to be guilty of the same”

King James VI & I, Basilikon Doron, Book I

That is, virtue is hard-won, and vice infectious. A people that is governed by the sinful will, consciously or not, itself be led to sin. God, therefore, will judge kings not only for their own character, but for the character of their people which results. A fallen father is reflected in a fallen son, and evil in society is always a mirror to the evil of its rulers.

The simplest and most practical way of guarding against malign influence, James maintained, is the regular reading of scripture. At the same time, the King reassures his son, the proper interpretation of said scripture may not always be as clear as one would like. For this, the King advised him to pray, though warns him of the difference between private and public prayer:

“Use often to pray when ye are quietest, especially forget it not in your bed how oft soever ye do it at other times: for public prayer serveth as much for example, as for any particular comfort to the supplicant”

King James VI & I, Basilikon Doron, Book I

In other words, the most fruitful reflection is far more likely to be found in moments of peace, when one is alone.

The King rather poetically concludes the first book with wisdom appropriate to all men:

“Keep God more sparingly in your mouth, but abundantly in your heart; be precise in effect, but social in show: declare more by your deeds than by your words, the love of virtue and hatred of vice: and delight more to be godly and virtuous indeed, than to be thought and called so; expecting more for your praise and reward in heaven, than here”

King James VI & I, Basilikon Doron, Book I