The Godfather of Fascism

What you can learn from the most eccentric man of the 20th century…

Disclaimer: In this article, the term 'fascist' refers exclusively to Italian Fascism, a political phenomenon entirely distinct from German Nazism. The two movements are rooted in fundamentally different doctrines and should never be conflated.

Two weeks ago, I hosted a retreat with O.W. Root in northern Italy to discuss the Catholic philosopher Josef Pieper’s seminal work Leisure: The Basis of Culture. While most of the tour was spent in and around Bergamo, on Wednesday we took a trip to Lake Garda to visit what I called “the most eccentric stop” on our retreat.

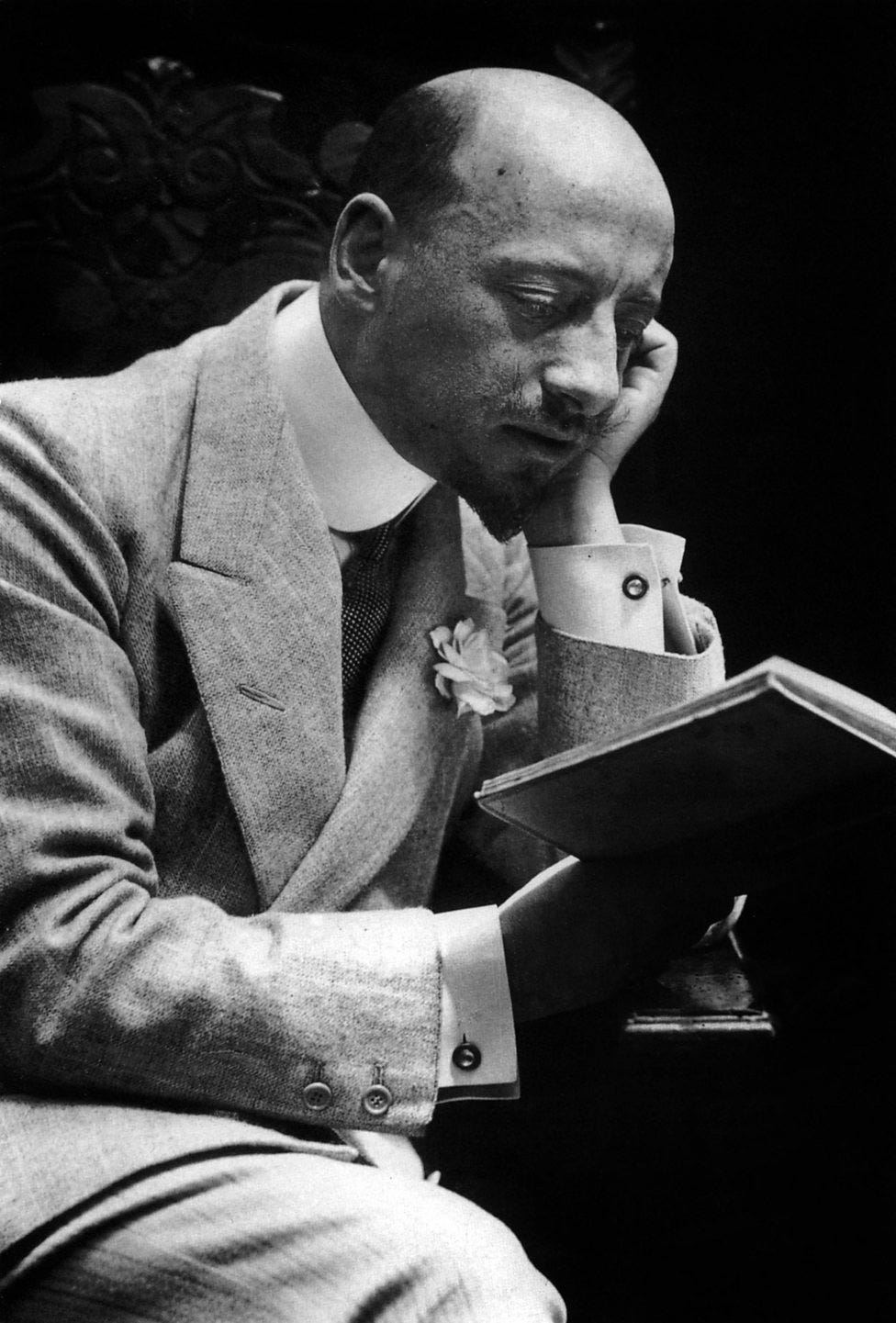

The destination was none other than the personal estate of Gabriele D’Annunzio, an Italian poet, playwright, war-hero, and the “godfather of Fascism”. Though a household name to all Italians, D’Annunzio is practically unheard of in the English speaking world — and to the extent that he is, he is uncritically derided and dismissed for his supposedly “fascist” beliefs.

The truth, of course, is far more complex. D’Annunzio originally rose to fame in Italy for his writing, becoming a best-selling novelist and considered by many of his contemporaries to be the greatest Italian poet since Dante. He then fought in WWI, and when Italy didn’t receive the land it was promised by the Allies (a betrayal which undoubtedly persuaded the Italians to join the Axis powers in WWII), he personally led a brigade into the Adriatic port city of Fiume, where he ruled as its Duce for the next 15 months.

Contrary to the popular “understanding” of the man, D’Annunzio was a far cry from an ardent Italian fascist — for starters, he never formally joined the party. More accurately, he was an extremist, as in someone who was extreme in every possible way. D’Annunzio was simultaneously a strongman, a dandy, an autocrat, an anarchist, a romantic poet and a serial philanderer.

His fashion sense and flare for political theatre (giving speeches from balconies, instituting the Roman salute, etc.) inspired the Italian fascists, though D’Annunzio considered them cheap knock-offs of himself. And despite his tumultuous relationship with Mussolini — his villa was essentially a golden cage financed by the fascists to keep him away from Rome and out of politics — still D’Annunzio met with the Duce to give him advice, and even tried to dissuade him from allying with Hitler.

So with all this in mind, why is it that, on a retreat about Leisure: The Basis of Culture, we chose to dedicate half a day to traveling to Lake Garda and touring D’Annunzio’s villa?

That is precisely what we’ll look at in today’s article, as we explore all that you can learn from the 20th century’s most eccentric character…

Zeal for Life

The decision to visit D’Annunzio’s estate — known today as Il Vittoriale degli Italiani — was based on the specific theme for that day, festival.

Josef Pieper describes the festival as such:

And just as Holy Scripture tells us that God rested on the seventh day and beheld that ‘the work which he had made’ was ‘very good’—so too it is leisure which leads man to accept the reality of the creation and thus to celebrate it, resting on the inner vision that accompanies it.

The strongest affirmation of this agreement is the celebration of a festival, where ‘to celebrate’, as Karl Kerényi says, is ‘the union of peace, contemplation and intensity of life’...

-Pieper, Leisure: The Basis of Culture, p. 29-30

This “intensity of life” is exactly what D’Annunzio embraced, in ways that few have replicated since his passing. He was a man who dared, adventured, and celebrated the reality of creation — in everything from words to wine to women.

Now of course, D’Annunzio often took this celebration to extremes, which we will discuss below. But the one thing he can never be accused of is a lack of zeal. He recognized there were many things in life far worse than death, and as a consequence, he threw precaution to the wind. He thoroughly disdained weakness, cowardice, and anything else that detracted from one’s ability to live life to the fullest.

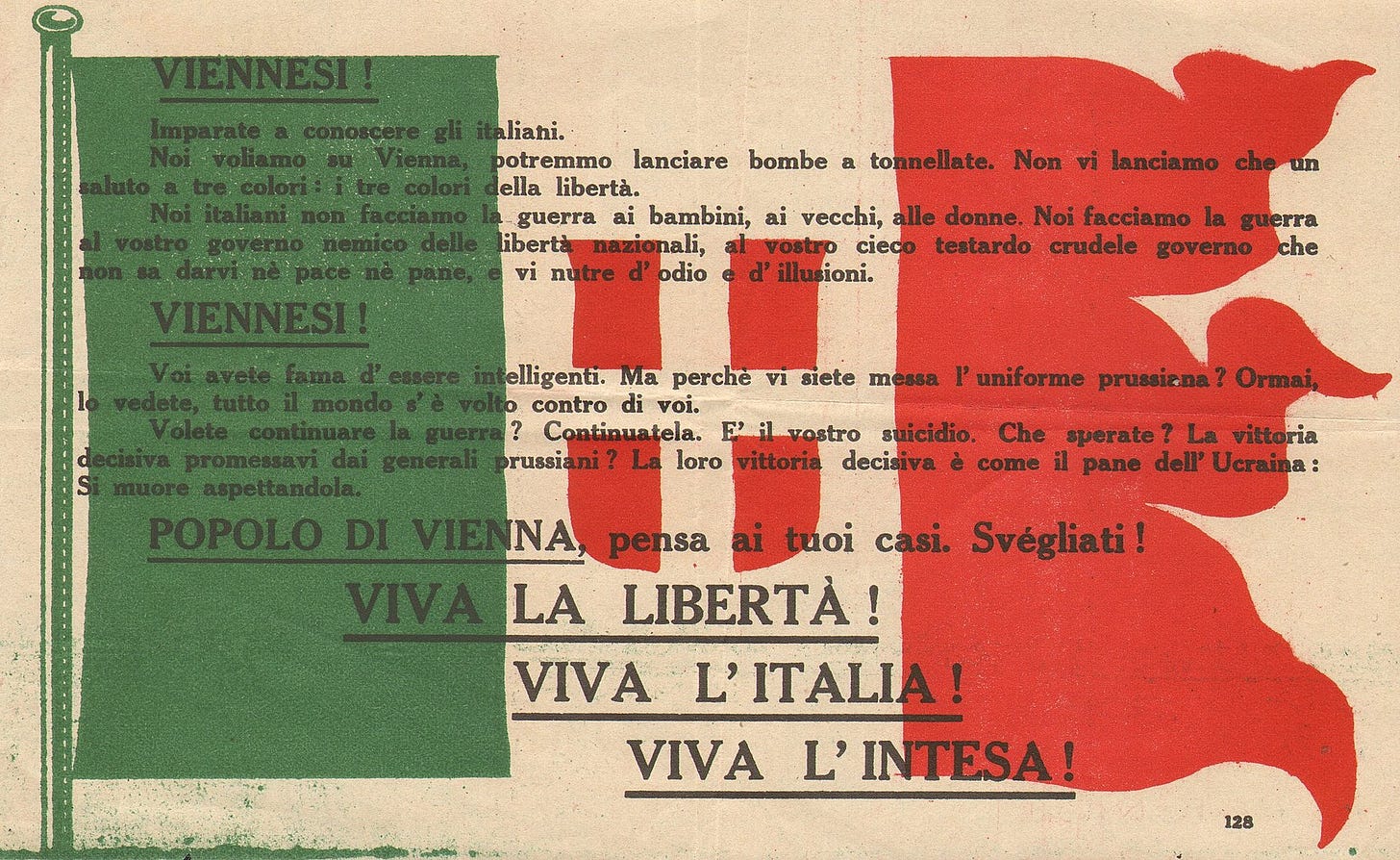

Perhaps the best example of this is D’Annunzio’s famous “Flight over Vienna”, where the poet led a squadron of Italian pilots on a daring aerial raid over the Austrian capital. Instead of dropping bombs, however, they dropped leaflets:

VIENNESE!

Learn to know the Italians.

We are flying over Vienna, where we could drop tons of bombs. Instead, the only thing we drop is a greeting of three colors: the three colors of liberty…

The Flight over Vienna was bold, theatrical, and utterly unnecessary — which is precisely why D’Annunzio orchestrated it. He understood the impact it would have on Italian morale, just as he understood the value of form over function and beauty over utility.

But most importantly, he understood what it meant to live with zeal, utterly unafraid of death. It’s not for nothing his personal motto was Memento Audere Semper — remember to always dare.

Going Too Far

Just as D’Annunzio’s life is a case study in passionate living, it is equally an example of overindulgence and excess. Here — and only here, after having properly lauded his virtues — is it appropriate to use him as an example of what not to do.

D’Annunzio was by many accounts the most famous man in Italy, and that fame left no small mark on his ego. Extravagance was the order of the day as sex, drugs, and drink filled his waking moments, and an inscription in one of his rooms attests to his belief in only five deadly sins (lust and greed being the two excluded). As a serial philanderer he took mistress after mistress, yet even here there is something admirable — for according to one such lover, D’Annunzio was “the only person” she had ever met “who had teeth in three different colors: white, yellow, and black.”

(Please don’t get me wrong here, I’m only highlighting the charisma one must have to overcome the unfortunate combination of short stature [D’annunzio was 5’3”], baldness, and black teeth — not endorsing adultery!)

D’Annunzio’s virtues regularly overflowed into vice, and his life is a good reminder that the same traits which lead to admirable virtues (such as courage, charisma, and daring) can easily lead to degenerate and dishonorable ones. It prompts a reflection on Karl Kerényi’s understanding of festival, where intensity of life can only be properly celebrated when it is celebrated in union with peace and contemplation…

Life as Art

Despite D’Annunzio’s many excesses, his story is a powerful reminder of what it means to cultivate your life as art. For D’Annunzio lived as though he were the protagonist in one of his own novels, the daring and romantic hero who flew over enemy skies, conquered foreign lands, and was adored by the masses.

The best legacy of this today is none other than D’Annunzio’s estate, whose name Il Vittoriale degli Italiani roughly translates into “the memorial to the victories of the Italians”. From the beginning of his residence there, D’Annunzio intended to make the estate a work of art in itself; a living shrine to Italian will, glory, and cultural destiny.

From its sprawling gardens, waterfalls, and pools to the lake-view amphitheater and the naval warship jutting out from the hillside cliff, D’Annunzio’s vision for the park both enthralls and inspires the over 300,000 visitors it receives every year. It is not only an enduring testament to the power of beauty, but a reminder that passionate decadence is a lesser sin than soulless austerity — for while the zealous man might err in his embrace of life, he can never be accused of not having lived it.

If you enjoyed this piece, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. You will unlock our entire back catalog of essays and video content, and get full access to our weekly members-only articles:

Ad finem fidelis,

-Evan

Salve - you should have translated the whole of the VIENNESI - it's very uplifting...

I lived in Rome for 15 years in the 60s and 70s and I know d'Annunzio only as a poet and writer, so it was great to learn about his other Casanova-like attributes... you have also put the longing on me to visit Lake Garda; I spend a lot of time in Sicily.