The Darkest Day in Roman History?

It wasn't what you think it was...

Sometimes, you are our own worst enemy. This is often particularly true in the face of adversity, where your own fear of losing can all too easily transform a minor setback into a disaster that is far more serious than it needed to be.

Nobody is truly immune to such psychology, which has struck even the most effective leaders in history. In Ancient Rome, the founder and arguably most successful ruler of the Roman Empire, the Emperor Augustus himself, fell victim to this following the Battle of the Teutoberg Forest.

As a result, the infamous battle in which three Roman legions were annihilated in the dark forests of Germany is still considered one of the most epochal disasters in history, despite Rome having at other times suffered materially far worse defeats.

But why is this?

To answer this question, today we compare the Battle of the Teutoberg Forest with another battle in which Rome suffered far a greater loss. We’ll examine the mistakes that caused the former to live forever in infamy, while the other was forgotten — and explore what this can teach you about responding to life’s worst disasters…

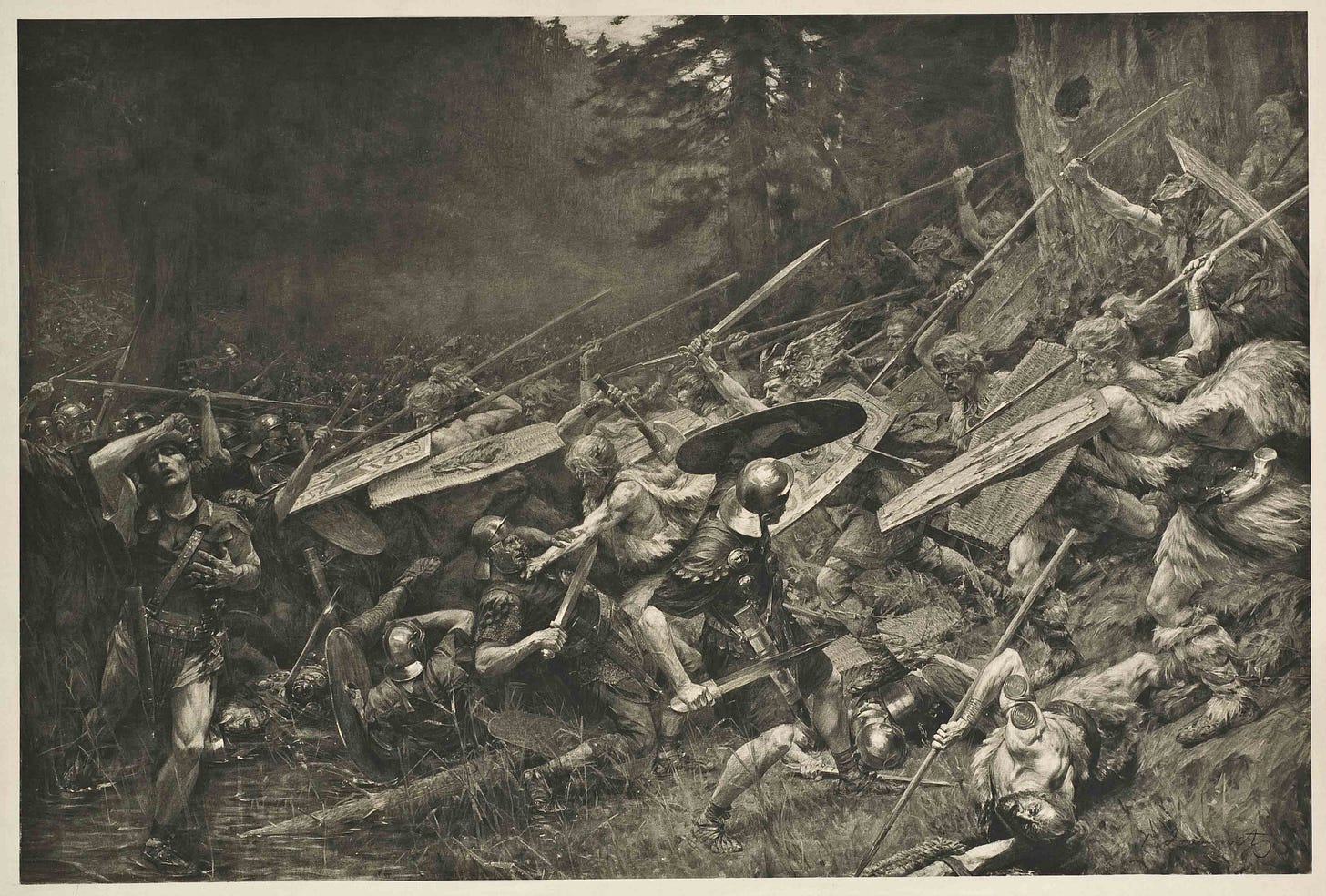

The Ambush in the Teutoberg

Through hindsight bias that has been dominant ever since the Teutoberg disaster, the expansion of Rome into Germany is often considered a classic example of imperial folly. In truth, however, it was the result of sound strategic thinking.

In an all but forgotten episode today, the Germanic Sugambri, Usipetes and Tencteri tribes all penetrated the frontier of Roman Gaul in 16 BC, catching and vanquishing the troops of the governor, Marcus Lollius. With the loss of at least one legion eagle in the debacle, the Emperor Augustus concluded, correctly, that Roman Gaul would not be secure without a significant buffer zone on the east bank of the Rhine. Roman military operations in Germany which followed, therefore, were guided by defensive, rather than offensive, necessity.

Over the next twenty years, Rome was largely successful in this endeavour. Following the successive appointments of Drusus and Tiberius, the adoptive sons of Augustus — and in the latter case, his successor to the emperordom — to command, by AD 6 the Roman frontier was fixed at the River Elbe. The operation, however, was stalled that year when a major revolt erupted in Pannonia, forcing the Emperor to redeploy Tiberius to confront it. As a result, Rome’s newly acquired German territories were entrusted to Publius Quinctilius Varus, who as the former governor of Syria, was a man of administrative rather than military experience:

“With this purpose in mind he entered the heart of Germany as though he were going among a people enjoying the blessings of peace, and sitting on his tribunal he wasted the time of a summer campaign in holding court and observing the proper details of legal procedure”

Velleius Paterculus on Publius Quinctilius Varus, Roman History, II.117

All seemed to be well, until it was suddenly very clearly not. In AD 9, Varus accepted the advice of local collaborators, particularly Arminius of the Cherusci tribe, trusting that the latter’s years of service in the Roman Army were a guarantee of loyalty. Thus when Arminius presented to Varus tidings of an uprising in the north, the latter was blissfully unaware that he was being deceived on a fatal scale.

There was no such uprising, only a trap deliberately laid by Arminius, which Varus, and the three legions left to him due to the Pannonian Revolt, marched straight into. Directed into routes hemmed in by the dense trees of the Teutoberg Forest, and slowed by incessant rain, the drawn out Roman column was set upon in a horribly protracted ambush. On the fourth traumatic day, Varus, deprived of all hope, committed suicide. What was left of the 20,000 men of the three legions either followed suit or were cut down in the forest, or else were captured and enslaved or tortured and sacrificed in grisly rituals to the bloodthirsty gods of pagan Germany.

The shock that rippled through the Empire in the wake of the disaster was legendary, and epitomised by the famous response of the Emperor himself:

“They say that he was so greatly affected that for several months in succession he cut neither his beard nor his hair, and sometimes he would dash his head against a door, crying: "Quintilius Varus, give me back my legions!" And he observed the day of the disaster each year as one of sorrow and mourning”

Suetonius on Augustus after the Battle of the Teutoberg Forest, Life of Augustus, 23

Fortunately however, the Germanic tribes were too disorganised and given to infighting to militarily exploit the rupture which had now opened up in the Roman frontier. The much feared collapse never materialised, reinforcements soon arrived from the Danube under Tiberius and Maroboduus, warlord of the powerful Marcomanni tribe, actually sided with Rome rather than Arminius.

Beyond the loss of life, the immediate consequences of the Teutoberg defeat were therefore curiously mild. Mild indeed compared to what Rome had suffered at the hands of another Germanic army, over a century earlier…

The Massacre at Arausio

In 113 BC, Rome experienced the exact worst-case scenario that many had feared would happen in the wake of the Teutoberg Forest massacre, when an enormous Germanic host swept aside a Roman army and poured over the Alps.

Through blind luck on Rome’s part, the hundreds of thousands of Cimbri and Teutonic warriors turned their rapacity towards Gaul and Hispania first, before eyeing Italy herself. Luck indeed, as Roman arms were for years bogged down in Africa fighting a war against King Jugurtha of Numidia — a conflict whose inept prosecution did much to reveal the degradation of republican Rome, and the extent of her corruption. Just how bad the situation had gotten, however, would be confirmed by Rome’s initial response to the critical threat to her north.

In 105 BC, the Cimbri warlord Boiorix prepared to target Italy. He would be met at the River Rhone by a Roman army commanded by the proconsul Quintus Servilius Caepio. The Senate however tasked a second army, commanded by the plebeian consul Gnaeus Mallius Maximus, to reinforce him, so that together they might halt the Germanic threat. Unfortunately however, in a typical display of the social dysfunction of the Roman Republic, Caepio resented ceding command to a man he deemed his social inferior:

“Servilius became the cause of many evils to the army by reason of his jealousy of his colleague; for, though he had in general equal authority, his rank was naturally diminished by the fact that the other was consul... Suspecting that Mallius might gain some success by himself, he grew jealous of him, fearing that he might secure the glory alone, and went to him; yet he neither encamped in the same place nor entered into any common plan, but took up a position between Mallius and the Cimbri, with the evident intention of being the first to join battle and so of winning all the glory of the war”

Cassius Dio, Roman History, XXVII.91

As a result, the two Roman armies failed to link up, allowing the Cimbri and Teutones to fall upon each with overwhelming numerical superiority, destroying them in detail in the Battle of Arausio.

The human cost of this debacle was astonishing. 80,000 Roman soldiers lost their lives, and if the account of Livy is correct, an additional 40,000 camp followers perished with them. It was quite possibly the single bloodiest day in Roman military history, worse even than Cannae.

The Battle of Arausio, therefore, dwarfed that of the Teutoberg Forest by every possible metric except one — consequence. So why is the former not burned into the collective memory of the West, but the latter is? The answer lies entirely in the response to both battles…

#1: Recognising the Actual Problem

The emotional reaction of Augustus to the Teutoberg affair was, according to Suetonius, matched by emergency measures:

“When the news of this came, he ordered that watch be kept by night throughout the city, to prevent outbreak, and prolonged the terms of the governors of the provinces, that the allies might be held to their allegiance by experienced men with whom they were acquainted. He also vowed great games to Jupiter Optimus Maximus, in case the condition of the commonwealth should improve, a thing which had been done in the Cimbric and Marsic wars”

Suetonius, Life of Augustus, 23

Cassius Dio, indeed, explicitly states that such measures were motivated by a certain panic, reporting that upon receiving word of the massacre:

“[He] mourned greatly, not only because of the soldiers who had been lost, but also because of his fear for the German and Gallic provinces, and particularly because he expected that the enemy would march against Italy and against Rome itself. For there were no citizens of military age left worth mentioning, and the allied forces that were of any value had suffered severely”

Cassius Dio, Roman History, LVI.23

This was complemented by an air of hysteria in Rome such that the Emperor grew suspicious of members of his own Praetorian Guard, sending those of Gallic or Germanic descent out of the city. Dio goes on to report the fateful conclusion of Augustus, which has since served as a cornerstone of the mythology of the Teutoberg disaster, that Rome’s misfortune was attributable to supernatural forces:

“For a catastrophe so great and sudden as this, it seemed to him, could have been due to nothing else than the wrath of some divinity; moreover, by reason of the portents which occurred both before the defeat and afterwards, he was strongly inclined to suspect some superhuman agency”

Cassius Dio, Roman History, LVI.24

It is impossible to conclude that the crucial final clause of the will of Augustus, released upon his death, five years later, “advising the restriction of the empire within its present frontiers” (Tacitus, Annals, I.11), was not motivated by shame and or embarrassment following the trauma of the Teutoberg.

The clause would have enormous implications for Roman imperial policy, establishing the perception that Rome had reached the permanent limits of expansion. The critical problem, however, is that this mythology was a self-fulfilling prophecy. Roman expansion was henceforth viewed critically simply because of Augustus’ will, rather than in light of actual conditions on the ground.

This has been allied to more modern arguments emphasising that Rome’s abandonment of the Germania project was dictated by geographic and economic motives. This received wisdom, however, ignores the successful and lasting expansions which later occurred in Britannia, the Agri Decumates and Dacia under Domitian and Trajan respectively. After all, there is no good argument why the ‘natural frontier’ of the Roman Empire in Europe could not extend beyond the Rhine when it had previously extended beyond the Alps — a far more formidable natural barrier.

All of this indeed has distracted from the actual issue, and the real reason the Teutoberg Forest was immortalised as a debacle and Arausio was forgotten.