The Builders of the World's Greatest Church

How their successes (and failures) shaped Rome forever...

On this day the 18th November 1626, after over 120 years of committed ambition, glorious successes, and near disastrous failures, Pope Urban VIII consecrated the most awe-inspiring building the Western world had ever seen.

Four centuries later, the Basilica Sancti Petri, or Basilica of Saint Peter in the Vatican, remains the benchmark for architectural ambition, awing the millions of visitors to Rome every year, faithful pilgrim and casual tourist alike.

There are of course many masterpieces that have marked the course of our history, from literature to painting, and the author of each is rightly remembered as a master in his own right. Yet Saint Peter’s was an achievement made possible by not one, but a roll call of many of the greatest talents our collective civilisation has ever produced.

Today, in a special piece to commemorate this most majestic of occasions, we consider the great men who made the great Basilica possible, and how each left his mark — for better or worse — upon the grandest church in Christendom…

Pope Nicholas V - Genesis

When Tommaso Parentucelli, the son of an impoverished Ligurian physician, was elected as Pope Nicholas V, on the 6th March 1447, Rome was a far cry indeed from the grandeur we celebrate today.

The ‘Babylonian Captivity’ of the Church, which began with Pope Clement V’s abandonment of Rome for Avignon in 1309, had condemned the Eternal City to one of the darkest periods in her history. Through uninterrupted decades of anarchy, violence and decay, the once great capital of the Roman Empire fell into beggary and squalor. In two painfully appropriate metaphors, a devastating earthquake in 1349 brought down the entire southern half of the Colosseum, while the complex of St. John Lateran, the historic cathedral of Rome, was gutted by repeated fires.

Only in 1420, when Pope Martin V at last returned the Papacy to Rome, could the formidable task of renovatio urbis — restoring the dignity of Rome — begin in earnest. Martin V would do an admirable job making the city suitable for habitation again, repairing her vital infrastructure, from bridges to aqueducts, and steering her out of her ‘emergency phase’.

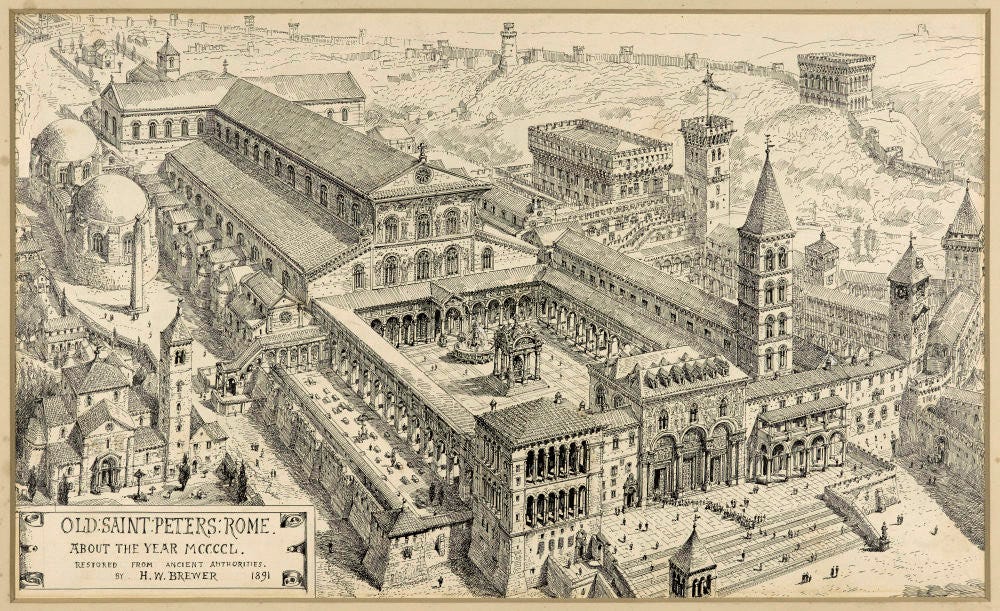

it would fall to Nicholas V, however, to finally re-embrace vision, and the Vatican would be central to that vision. The years, after all, had not been kind to the old Basilica of Saint Peter, which Emperor Constantine had erected over a thousand years earlier. Dilapidated and dingy, within living memory it had been used as a stable for the horses of occupying Neapolitan soldiers.

Thus did Nicholas resolve to rebuild the Basilica, and reassert Rome as the worthy seat of Western Christendom. To this end, Nicholas set aside 2,500 cartloads of stone — much of it ‘recycled’, shall we say, from the ruined Colosseum — along with part of the considerable revenues raised from the 1450 Jubilee. His death in 1455, however, and the distraction of his successors, would delay construction of the Basilica by fifty years.

It is thanks to Martin V that the Roman Renaissance was even possible. It is to Nicholas V, however, that we owe its spark, and the idea behind its most monumental symbol. The duty of kindling that spark, and building that symbol, however, would fall to others…

Donato Bramante - Work Begins

With Rome now a flourishing capital once again, and Papal authority in central Italy far steadier, in 1505 the formidable Pope Julius II revived the dream of Nicholas V in ambitious style - Old Saint Peter’s would be demolished, and a new, far greater Saint Peter’s would rise from the rubble.

The destruction of one of the foremost centres of Christian pilgrimage, of course, did not occur without controversy. Fortunately however, Renaissance Rome was well equipped with men who inspired confidence that something better could indeed replace it. Thus did Julius turn to a man who has since been eclipsed in fame, but without whom the careers of many illustrious Italians would have stalled prematurely — Donato Bramante.

One of the first of the ‘greatest generation’ of Renaissance masters, birthed by the cultural blossoming and inspired court of Federico da Montefeltro, Duke of Urbino, Donato Bramante walked so that Raphael and Michelangelo could run. In 1502, just two years before Raphael painted his breakthrough piece — the Sposalizio della Vergine, Bramante had begun work on a commission from the Catholic Monarchs, King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Queen Isabella I of Castile, victors of the Reconquista, to rebuild the complex of San Pietro in Montorio on the Janiculum Hill in Rome. The centrepiece which resulted, one of Bramante’s masterpieces, is the round Tempietto, or ‘Little Temple’, which marks the location of Saint Peter’s crucifixion.

It is almost certainly this work that earned Bramante the favour of Julius II, and it is certainly no coincidence that the Tempietto looks like a ‘prototype’ of the Saint Peter’s Basilica we know today.

“And so, the Pope having resolved to make a beginning with the vast and sublime structure of S. Pietro, Bramante caused half of the old church to be pulled down, and put his hand to the work, with the intention that it should surpass, in beauty, art, invention, and design, as well as in grandeur, richness, and adornment, all the buildings that had been erected in that city by the power of the Commonwealth, and by the art and intellect of so many able masters”

Giorgio Vasari, Life of Donato Bramante

Thus on the 18th April 1506, Julius II laid the foundation stone of New Saint Peter’s Basilica, as Bramante began the most arduous task of all — translating decades of hazy dreams into realities in stone.

By the death of Julius in 1512 and his own two years later, Bramante had coordinated a workforce of 2,500 men with sufficient diligence to bring the project “to the height of the cornice [level with the top of the columns], where are the arches to all the four piers” (Vasari, Bramante), and had begun work on the vaults.

Fortunately, another was ready to take his place, in the form of a young prodigy who Bramante himself had personally introduced to Rome…

Raphael - A Western Church

Arguably the greatest painter the world has ever seen, Raphael’s aesthetic talents were not limited to the canvas.

A fellow alumnus of the court of Urbino, Raphael was already revered by 1514, when Pope Leo X passed the architect’s baton from Bramante to him. Just three years earlier, he had completed the Stanza della Segnatura in the Apostolic Palace, whose frescoes are rivalled only by those Michelangelo was working on concurrently in the Sistine Chapel.

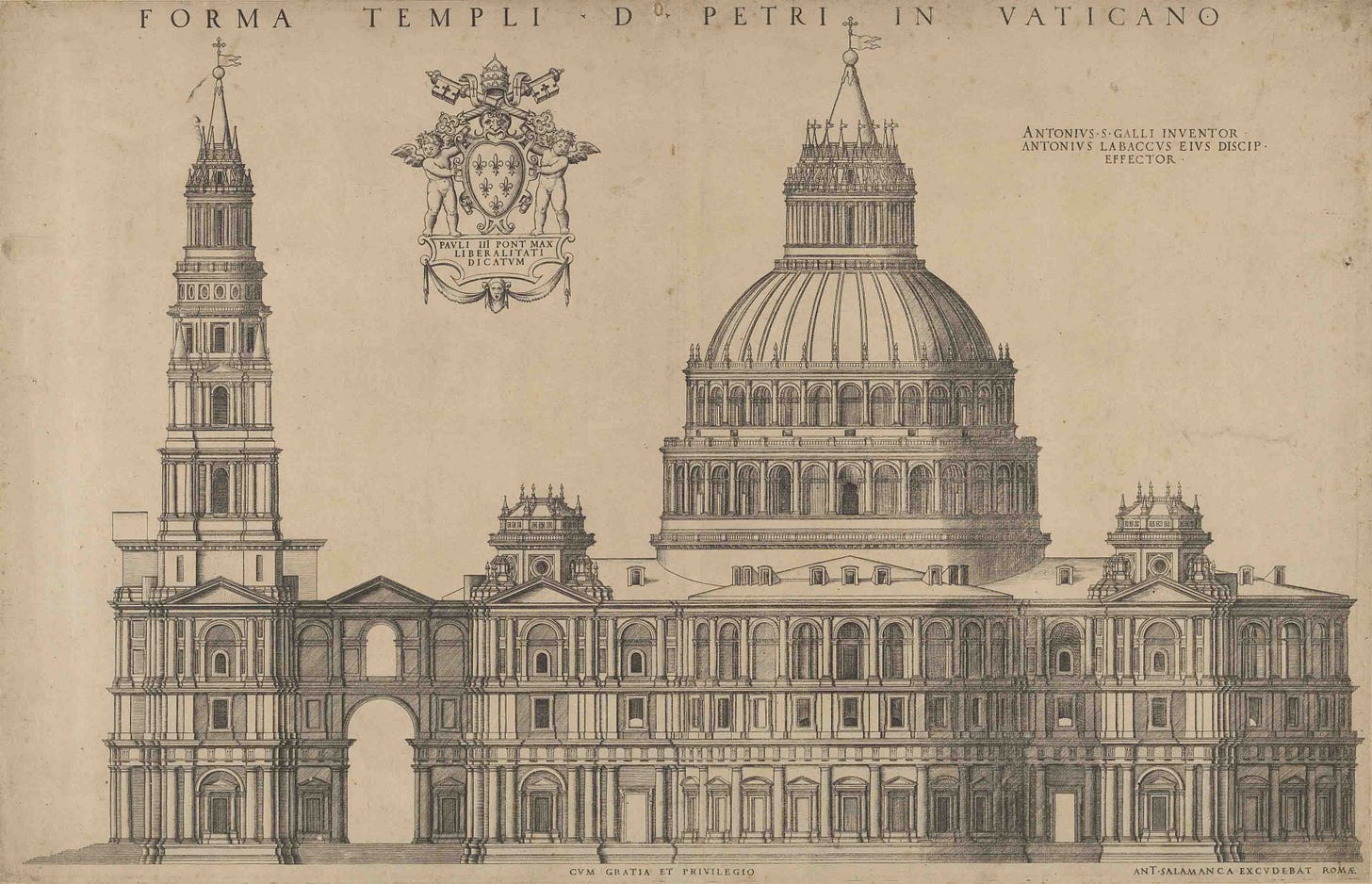

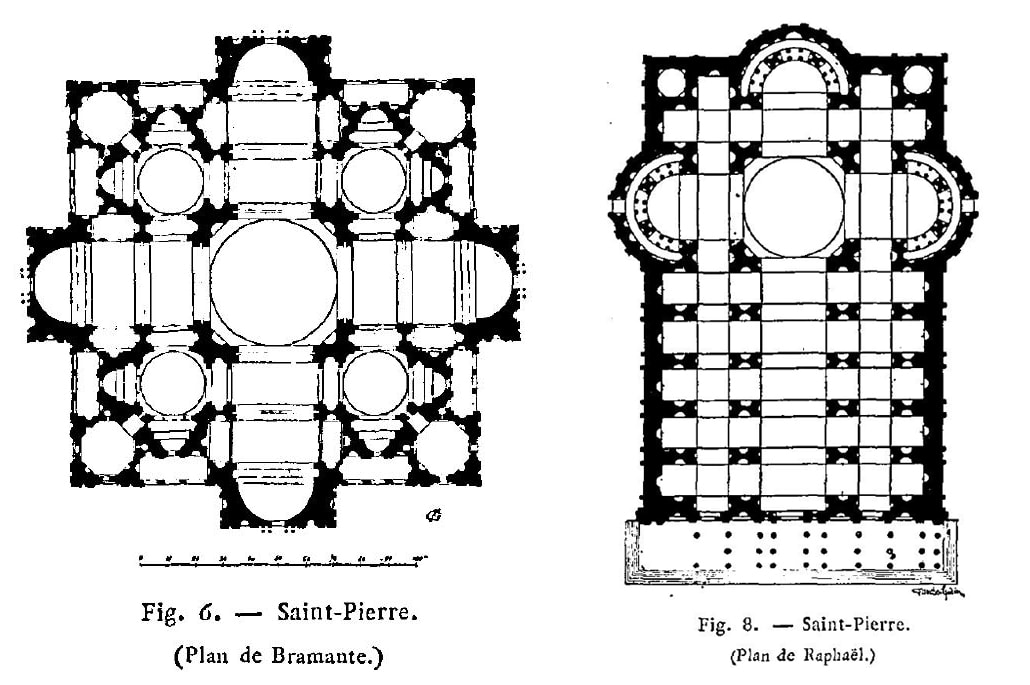

Now chief-architect of the Fabbrica di San Pietro — the committee still today charged with overseeing the condition of Saint Peter’s — Raphael would quickly leave his mark on the great Basilica. Donato Bramante, after all, had conceived of a ‘Greek Cross’ plan for Saint Peter’s. That is, a symmetrically balanced basilica, in which each arm was of equal length. Raphael however, revised the plan to a ‘Latin Cross’, in which the forward ‘arm’ is longer than the others. Saint Peter’s Basilica would now be more firmly of the Western rather than Eastern tradition, and would now have a nave.

Raphael, however, burned the candle of life at both ends. Alongside his duties at Saint Peter’s, Urbino’s most famous son would conduct the earliest professional surveys of Antiquities in Rome, design the suburban Villa Madama and the tomb of Agostino Chigi — the wealthiest man in Rome — as well as produce other timeless masterpieces from the Villa Chigi (today’s Villa Farnesina) to the Vatican loggias.

His own sudden and tragic death at 38, on the 6th April 1520, was recognised even at the time as a devastating blow to civilisation itself, plunging the arts into a profound crisis of confidence it has been reacting to ever since. It would also plunge the Fabbrica di San Pietro into disarray, as work on the Basilica stalled amid competing visions, fluctuating resources and an increasingly unstable Europe.

Seven years later, Roman confidence would be severely shaken by one of the greatest disasters in her history, as a renegade army of mercenary German landsknechts ruthlessly sacked the Eternal City, pillaging her treasures and torching many of her quarters.

The vision of Nicholas V, it appeared, was heading for oblivion. It would take a man of extraordinary will to rescue it…

Michelangelo - Salvation

“Finally his Holiness, inspired, I believe, by God, resolved to send for Michelagnolo”

Giorgio Vasari, Life of Michelangelo

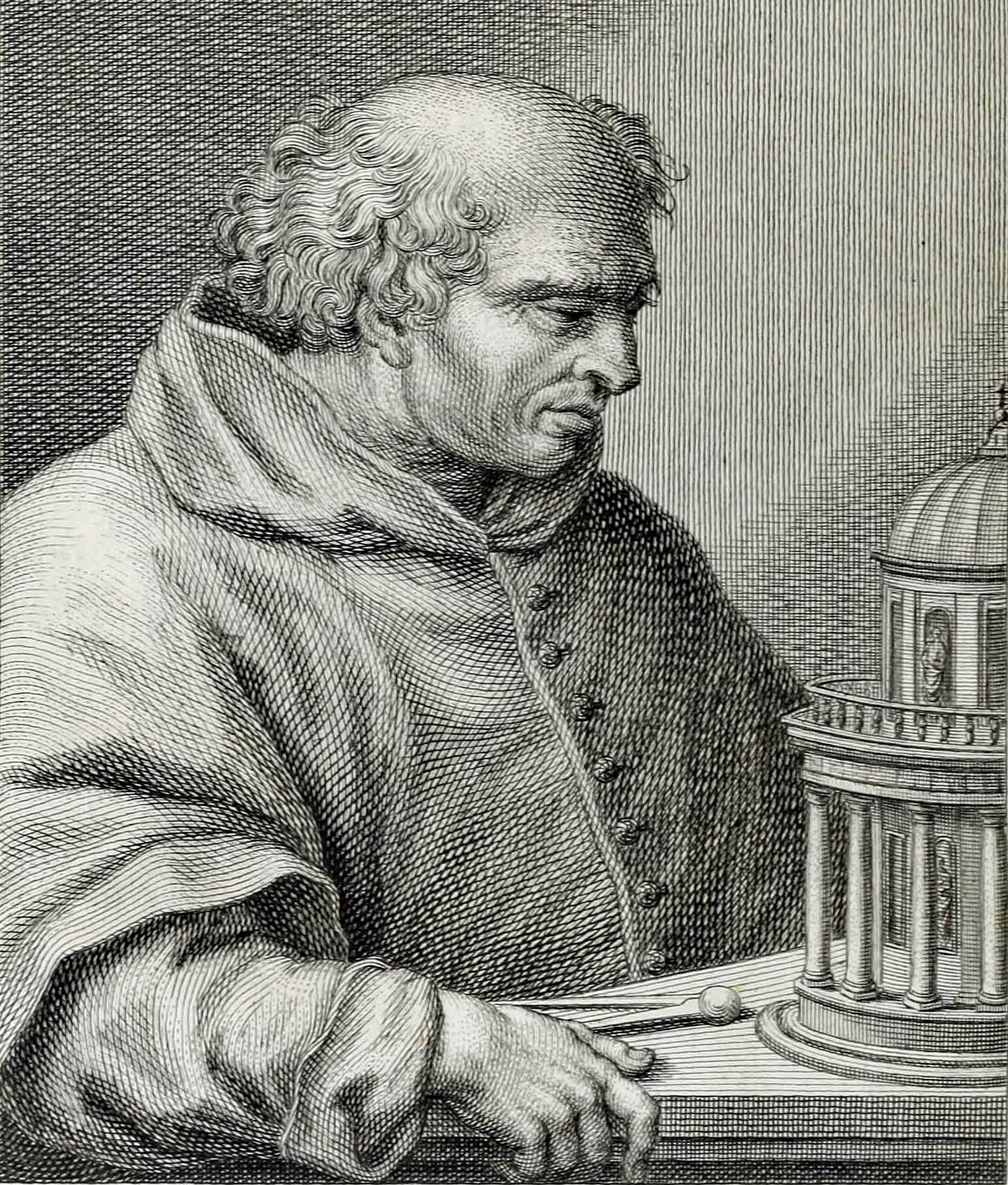

When, in 1546, Pope Paul III appointed the seventy one year old Michelangelo as head architect of Saint Peter’s, the Tuscan master inherited an unholy mess.

He had accepted the commission most unwillingly, arguing that architecture was not his calling, and only the stern insistence of the Pope brought Michelangelo to his senses. Though fighting the stresses of old age and exhaustion, the mind and pride of Michelangelo remained sharp and ready. Progress on Saint Peter’s had been barely perceptible since Raphael’s time, and he deplored the waste which had characterised the intervening twenty five years.

Typical of that waste was the wooden model that Antonio da Sangallo had produced, at eye-watering expense in time and money, with a proposed update of Raphael’s vision.

Lambasting the project as more Germanic than Italian, excessively overburdened with ornament, to the extent that the interior would be plunged into darkness by the many obstructions, Michelangelo promptly discarded it. Whereas the model of Sangallo had taken years to make, at a cost of four thousand crowns, Michelangelo would produce his own in less than two weeks, for a mere twenty five crowns.

Saint Peter’s Basilica was to be a Greek Cross once again, faithful to Bramante’s original plan, and thus Michelangelo convinced Paul III that by showing more restraint than Sangallo, it was possible “to execute it with more majesty, grandeur, and facility, greater beauty and convenience, and better ordered design” (Vasari, Michelangelo). The Pope, impressed, issued an act of motu proprio, granting Michelangelo full discretion over the Fabbrica di San Pietro. Michelangelo, in turn, in appreciation for this vote of confidence, declared that since he would be working for the love of God, he would accept no salary for the position.

Thus the more streamlined plan was approved, and works recommenced. The centrepiece of it all, however, would be a dome that transcended anything that Bramante could possibly have conceived of.

Observing that the central pilasters of the structure, which Bramante had first erected and Sangallo had left untouched, were inadequate for the structural load, Michelangelo had them filled with far more robust materials. At the same time, he had two spiral staircases built beside them, by which men and beasts of burden could transport material to the roof far more efficiently and safely.

The project was back on track, though even with a mind as magnificent as that of Michelangelo Buonarroti, there were limits to how quickly professional work could be done.

Fortunately, when the Master himself passed away in 1564, at the ripe age of eighty eight, enough of the base of the Dome had been completed that Michelangelo’s successors needed to simply follow his instructions, rather than innovate new solutions.

Unfortunately, however, Michelangelo’s plan would be permanently maimed by one such successor, whose contributions to Saint Peter’s almost led to the building’s catastrophic collapse…