Pope Leo's Guide to Recovering from Catastrophe

In 1823, one of the greatest churches in Christendom burned. Pope Leo XII's response is an inspirational guide to recovering from catastrophe...

Tragedies happen. How you respond to them, however, determines whether the resulting trauma is temporary or permanent.

One does not need to look far in the world today to see innumerable examples of tragedies exacerbated into catastrophes by indifference, incompetence or even active malevolence.

202 years ago today, Rome stood at a similar crossroads, as she was faced with a historic disaster that tore at the soul of the entire Western world. On the night of the 15th July 1823, an all-consuming fire devastated one of the holiest sites in Christendom — the mighty Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls, which had stood since the days of Emperor Constantine over the tomb of the Apostle Paul himself.

Just weeks later, Pope Pius VII died, compounding an annus horribilis for the Catholic Church. With the resulting conclave electing a sickly successor, there appeared little cause for optimism. But the new pontiff, Pope Leo XII, quickly exceeded all expectations. Battling illness and financial difficulties, Leo blended visionary idealism with down-to-earth pragmatism to resurrect something glorious from the smouldering ashes of the once-great Basilica.

Today, we tell the story of how Leo did the impossible to rebuild St. Paul Outside the Walls, and what his story can teach you about turning tragedy into lasting triumph…

The New Fire of Rome

“I visited St. Paul’s on the day following the fire. I found in it a severe beauty and an impression of calamity such as only the music of Mozart, among the fine arts, can suggest. Everything conveyed the horror and the disorder of the disaster; the church was cluttered with smoking and half-burnt beams; great fragments of columns split from top to bottom threatened to fall at the slightest jar. The Romans who filled the church were thunderstruck”

Stendhal, Promenades in Rome

Such was the agony to which Rome and the world awoke on the morning of the 16th July 1823. By the carelessness of a single worker, who had neglected to extinguish his lamp at the end of his shift the day before, one and a half thousand years of history was burned to cinders.

Consecrated by Pope Sylvester in AD 324, Saint Paul Outside the Walls was rivalled only by Saint John Lateran as the oldest church of Rome, and oldest basilica in Western Christianity. When all others had been remodelled or rebuilt to Renaissance and Baroque tastes, Saint Paul’s was the only one of the great basilicas of Rome that had retained its ancient Constantinian character throughout its history.

All that remained of that now was a ravaged shell, the fire having destroyed all that was beautiful save the mosaics of the apse and arch, with the firemen barely able to save the monastery and cloister.

Yet in this moment of crisis, the Papacy itself was a living metaphor for the tragedy outside the walls. Nine days earlier, the eighty year old Pope Pius VII had fallen and fractured his femur, rendering him bedbound and tormented by excruciating pain. So terrible was his condition that Cardinal Secretary of State Ercole Consalvi, fearing the effect of the terrible news, forbade any from informing Pius of what had happened at Saint Paul’s, where the pontiff had himself as a young man served as a monk.

It was to little avail, for barely a month later, on the 20th August 1823, the Pope who had once parlayed with Napoleon and endured incarceration in France breathed his last. A historic pontificate of over 23 years was at an end, and the fate of Saint Paul’s would have to wait until the beginning of another.

The resulting conclave occupied almost the entirety of September, prolonged by the deep rifts in post-Napoleonic Europe. The conservative zelanti faction, indeed, were furious when their candidate, Cardinal Severoli, was vetoed by Austria. Severoli, however, quickly outmanoeuvred the moderates by rallying support for another zelante — a well-mannered Umbrian cardinal by the name of Annibale della Genga...

The New Pope & The Challenge Ahead

Sixty three years of age and plagued by illness, della Genga was horrified at the turn of events. When on the 28th September, he received the majority vote, he implored the College of Cardinals to reconsider. “You are electing a dead man”, he famously exclaimed, revealing his swollen and ulcer-ridden legs.

His humility, however, only further convinced his colleagues of his righteousness, while his ideological foes were content to bear what was surely to be a brief pontificate. With all present thus insisting, della Genga bowed to their decision, and took the name of Pope Leo XII. If his opponents had hoped his reign would be feeble and brief, however, they were to be sorely mistaken.

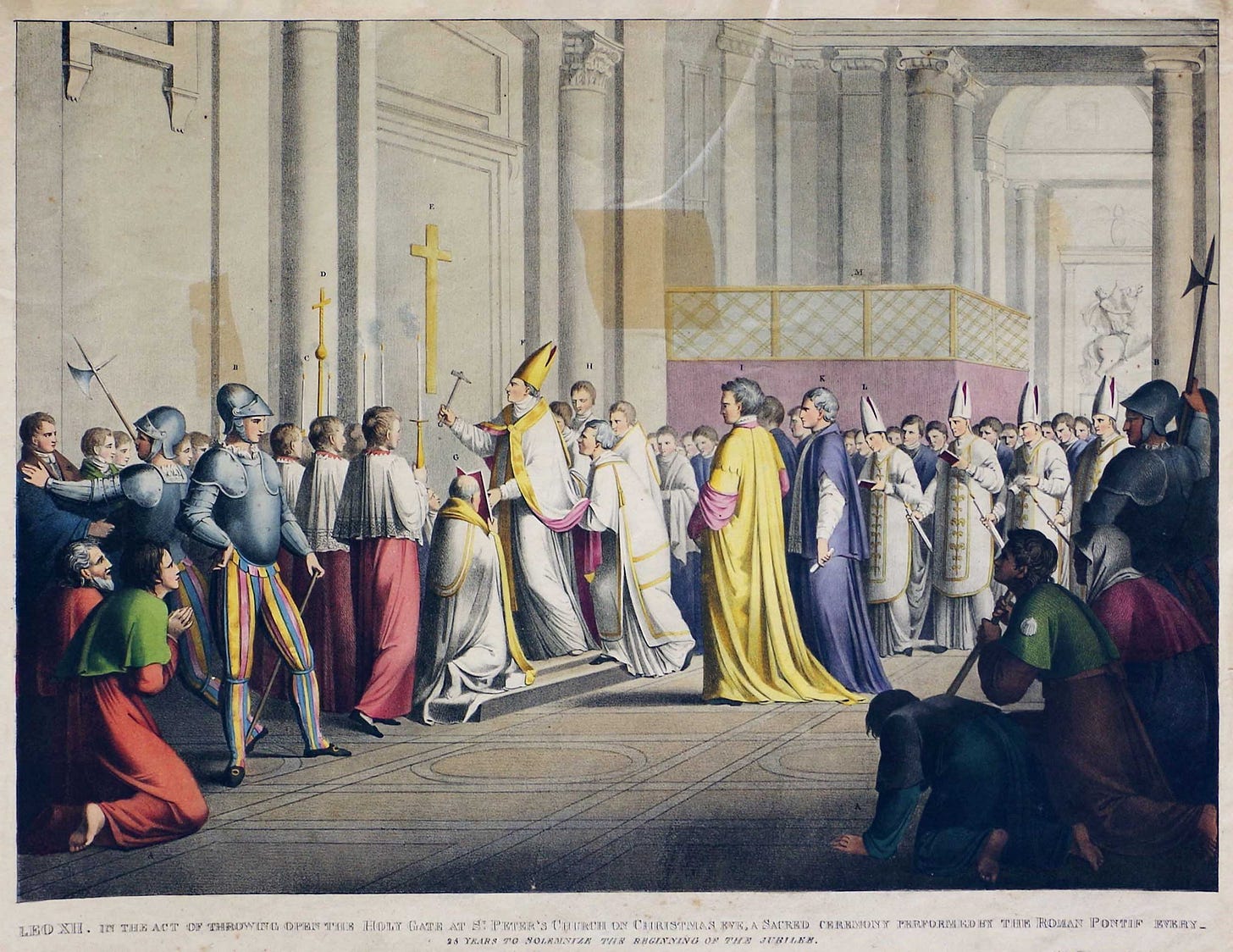

Following his coronation on the 5th October 1823 his death was widely expected before the year’s end. However, by Christmas he had suddenly rallied, and while his physical form remained frail, his management of the Church was anything but.

Unapologetic in his condemnation of the ‘de-Christianisation’ of Europe following the French Revolution, Leo moved quickly to condemn the secret societies which had enabled it and expunge them from his domains. Likewise, ancient customs and traditions received the Pope’s enthusiastic support, while a raft of laws on public decency were passed, including on the manufacture and sale of appropriate clothing for women. At the same time, Rome’s ambassadors — under Leo’s close scrutiny — lobbied tirelessly against the persecution of Catholics in Europe, successfully combatting governments in the Netherlands and the United Kingdom, where the Relief Act finally achieved Catholic Emancipation in 1829.

Yet the ruins of Saint Paul Outside the Walls would not be neglected by this energetic surge. Rejecting the many contrary calls for a ‘modern reimagining’, Leo ordered the reconstruction of the Basilica Dov'era, Com'era (‘Where it was, as it was’).

With the 1825 Jubilee imminent however, when pilgrims would be expected to visit the major basilicas of Rome, Leo XII was fighting against time, for his health, and for Saint Paul’s…

The Call to Arms

When it became clear that the damage to Saint Paul’s was so extensive that a wholesale rebuilding was required — which could not possibly be completed in the months that remained before the Jubilee — Leo XII was pushed towards an unenviable choice: abandon the site or build on a more modest scale.

The Supreme Pontiff, however, rejected this false binary. What he did next was entirely unprecedented, but it was exactly what was needed to achieve his goal. Fortunately for us, we have the entire plan documented in his own words….