How to Build Bridges in a Time of War

Lessons from a Soldier of Christ...

How can you build bridges between bitter ideological foes? It is a question that has rarely been more relevant. Fortunately for us, however, our age of all-or-nothing civilisational conflict has a precedent that hides in plain sight within our history.

The fallout of the Protestant Reformation, after all, triggered a rupture of the very fabric of Europe, which smouldered over the course of decades before erupting into all-out civil war in Christendom. It tore apart empires, states and families, entrenching the notion that ‘wrongthink’ could be punished by ostracism, or even death.

It was a conflict that divided the West like few others, and the Church faced a formidable task in building bridges at a time of extreme hostility. So in 1545, Pope Paul III turned to a man who was arguably doing more of God’s groundwork than any other then alive — Saint Ignatius of Loyola, the soldier turned cleric who just five years earlier had founded the Jesuit Order.

When the Council of Trent opened in 1545 to decide upon the Catholic Church’s response to the Protestant Reformation, Paul III asked Ignatius to send three of his followers to help guide it. In order to prepare the chosen brothers, Ignatius wrote them a remarkable letter to prepare them for this formidable task.

Today, we consider what that letter, and its author, can teach you about opening doors with others who think differently to you…

Earthly and Spiritual War

“Up to his twenty-sixth year the heart of Ignatius was enthralled by the vanities of the world. His special delight was in the military life, and he seemed led by a strong and empty desire of gaining for himself a great name”

Saint Ignatius of Loyola, Autobiography, I

Saint Ignatius was uniquely qualified to speak about conflict. To understand how and why, we first need to consider how he came to prominence in the first place.

The youngest son of a Basque nobleman, Íñigo de Oñez y Loyola, as he was originally called, was enamoured by tales of chivalry, and yearned to live a life worthy of medieval poetry. So when France and her allies attacked the city of Pamplona in 1521, it appeared his hour of glory had come.

The young nobleman’s romantic dream however was abruptly punctured by a French cannonball, which on the 20th May 1521 shattered one of his legs and maimed the other. As he fell in agony, so too did Pamplona, and thus Íñigo, a literally broken man, was borne away upon a stretcher to Loyola to rebuild his strength and his life.

To pass the interminable hours of his excruciating recovery, he asked for books of knightly romance. But there were none available, only accounts of the lives of Christ and of the Saints, which he reluctantly accepted. Yet as he pored over those pages, he suddenly found himself torn between godly and earthly things. Soon, “He learned by experience that one train of thought left him sad, the other joyful“ (Autobiography I), and thus upon his recovery, Íñigo cast aside his steel weapons and lavish finery, and now as Ignatius, took up the arms of Heaven.

Through frequent illness, continual poverty, fatigue and exposure to the elements, Ignatius devoted himself to aiding his fellow man in their common spiritual war. Along the way, Ignatius became well-accustomed to defending his ground in such conflict. Being neither ordained nor formally educated in Theology, he found himself frequently in prison and under interrogation for ‘unauthorised preaching’. His humble acceptance and faultless grasp of doctrine, however, allowed his persecutors no ammunition for a successful prosecution.

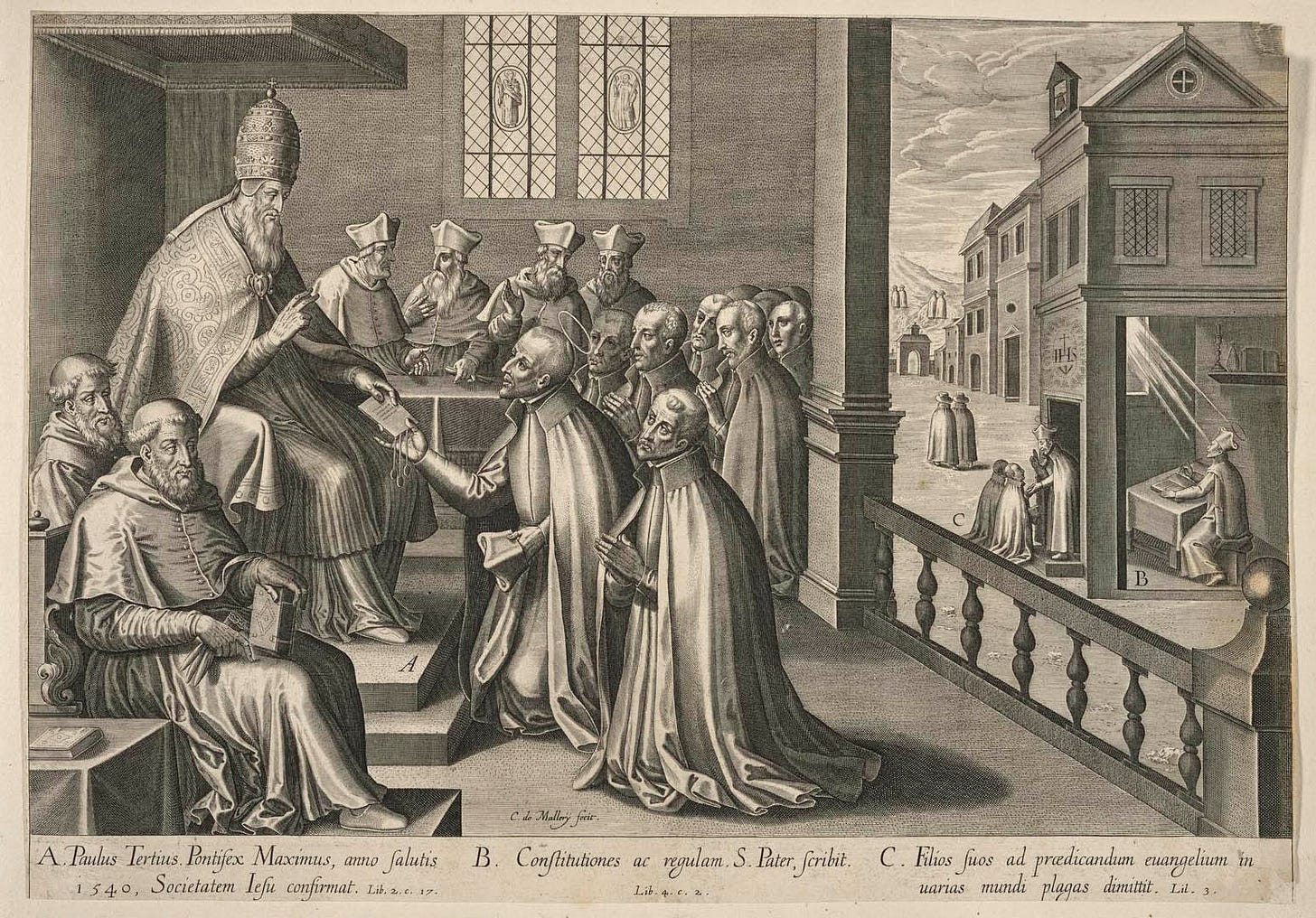

Through his unceasing charity and endurance through these trials, he swiftly attracted a small yet diligent band of followers, which on the 27th September 1540 would formally be established as the Society of Jesus, or Jesuit Order as it is today commonly called. With the fallout of the Protestant Reformation spreading, the Society’s foundation came not a moment too soon either. In 1545, after years of diplomatic wrangling, the 19th ecumenical council of the Church opened in the Alpine city of Trent, with the express aim of responding to the growing schism in Europe, and exploring potential reform of the Church.

With Ignatius having been elected General of the Society of Jesus, and now fully occupied with its administration, Paul III asked him to dispatch three of his companions to serve as Papal theologians to the Council — Diego Laínez, Alfonso Salmerón and Peter Fabre. Fully understanding the gravity of the situation, in the spring of 1546 Ignatius wrote a letter to them, containing a list of instructions on how to conduct themselves at Trent.

As a man thus versed in all arenas of conflict, the advice Ignatius offered is valuable to anyone who is facing difficult conversations in strained times…

On Dealing with Others

Saint Ignatius authored many letters during his mature years. To the Society at Trent, however is extraordinary among them. The letter is helpfully divided into three sections, concerning how to deal with others, how to help souls, and how to help oneself.

The first and most pressing section, On Dealing With Others, takes the form of seven brief and numbered points, written in such a manner that the three men, after reading it once, could refer to it again at the beginning and close of each day during their time in Trent. Let us consider them together now:

“1. Just as in conversing and dealing with many persons with a view to the health and spiritual advantage of souls much can be gained with divine assistance, so on the contrary, in such conversations, if we are not watchful and favoured by Our Lord, much is lost on our part, and sometimes on that of all. And since in accordance with our profession we cannot avoid such conversation, the more we are prepared and armed with some predetermined purpose, the more evenly shall we go on in Our Lord. The following are some points, to which we may add others, and from which we may subtract, to keep ourselves in Our Lord.”

When faced with a wide range of viewpoints, many closely and passionately held, it can be all too easy to get lost in the noise.

Knowing that this will happen, therefore, one should do two things. Firstly, enter such a discussion being ready to hear all sides, no matter how acrimoniously they are presented. Secondly, establish in advance what the higher purpose of the discussion should be, to ensure it is not derailed either by yourself or others.

“2. I should be slow to speak, but deliberate and sympathetic, especially if it concerns matters that are being dealt with, or likely to be dealt with, at the Council.”

Never intervene in haste or in the heat of emotion, otherwise you run the risk of undermining what could have been a valuable contribution before you have even made it.

“3. I should be prudent in my speech, helping myself with what I hear, calmly noticing and making myself acquainted with the understanding, the feelings, and the desires of those who speak, so as to be able the better to make answer or to be silent altogether.”

Make it clear that you have listened to what others have said before responding, and adapt your delivery to show it. Should your words give any hint of being a pre-prepared speech, pronounced as if you were the first speaker of the day, you will only intensify frustrations.

Asking questions on the other hand, to be sure you have understood the positions of others, can only build good faith and make others more willing to lend you their ears.

“4. When matters of this kind are being discussed, we should give the reasons of both sides, so as to show ourselves not inclined merely to our own side, and not to leave anyone dissatisfied.”

Be indifferent to the emotion, yet involved in the substance of the arguments presented. Do not allow your own convictions to get in the way of allowing each party a fair opportunity to present its case. If people feel that the format of the discussion is stacked against them, you will never win them over to your cause.

“5. I should not bring forward as witness on my side any persons, especially if they are of great consequence, unless it be in matters that have been duly considered from all sides; thus showing myself equally friendly to all, with no marked inclination to anyone.”

Never assume that a particular person is on your side if you have never really discussed the issue at hand in real depth with them beforehand. People may have been polite to avoid conflict, giving the false impression of support, which may come back to haunt you when they are suddenly in the company of others who are like-minded. Be alert, too, to any potential accusation of undue bias when it comes to choosing who should speak next.

“6. If the matters discussed are so clear that one could not or ought not to remain silent, I should give my opinion on the subject with the greatest possible calm and humility, ending in deference to better judgment.”

If the situation requires you to offer your own opinion, do so with the awareness that the force of emotion is no substitute for a reasoned argument. Do not simply say that you are aware there are other opinions, but show that you understand them, and indicate your openness to be persuaded by a potentially stronger case.

“7. Finally, in conversing about and in discussing matters of doctrine acquired or infused, when I wish to deal with them, it is of great advantage not to consider my own leisure, or my want of time, or my pressure of business, i.e., not my convenience, but to adapt myself to the convenience and leisure of the person with whom I wish to deal, in order to move him to the greater glory of God.”

If the discussion reaches an especially poignant or crucial moment, perhaps because it has revealed an underlying concern that is more important to the participants than you had initially anticipated, do not allow arbitrary pressures or rules to needlessly spoil it.

Showing a little flexibility, and thus a willingness to endure a certain degree of inconvenience on your part, if it helps to resolve a real problem — or at least provide a chance to resolve it — can readily fill a deep well of goodwill.

Of course, it is all well and good showing respect during difficult conversations. But none of this matters if you do not also follow what Ignatius had to say next…