How to Pick Your Team

How the world’s top explorer hired his men...

All that I can remember of it is that I was asked if I had good teeth, if I suffered from varicose veins, and if I could sing.

-Reginald James on his job interview with Shackleton

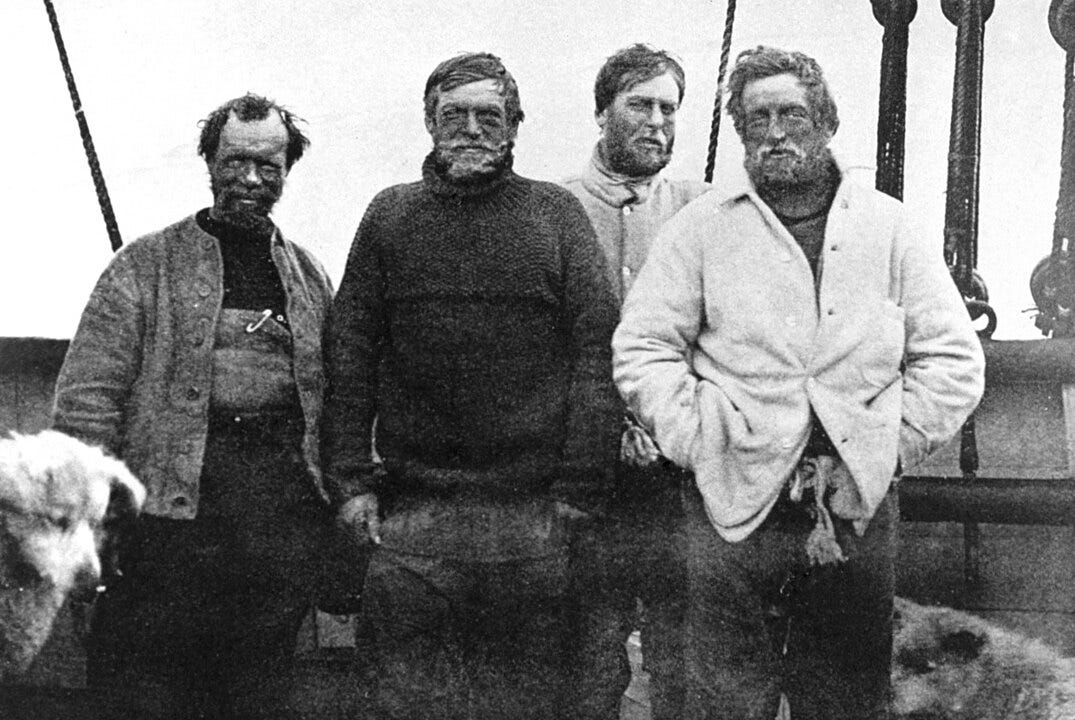

Few explorers are more deserving of their fame than the legendary Sir Ernest Shackleton. Having set out to cross the Antarctic in 1914, his expedition was quickly met with disaster when his ship was trapped and destroyed by pack ice.

What followed was the greatest survival story of the 20th century, if not of all time.

Stranded with 27 men, Shackleton helped his crew survive on shifting ice flows — not even solid ground — for 497 days until they finally reached Elephant Island, a desolate rock in the Antarctic Ocean. Leaving the rest of his crew behind, Shackleton then set off with five others in a 22-foot lifeboat and sailed over 800 miles through hurricane-force seas to seek help on the scarcely inhabited South Georgia Island.

Navigating with nothing more than a sextant and sheer instinct, the five men finally made landfall after 16 days. They then crossed 32 miles of the island’s uncharted mountains and glaciers to reach town, and finally returned to rescue the rest of the crew. Incredibly, in the 19 months since their ordeal had begun, not a single soul had been lost.

None of this, however, would have been possible were it not for the absurd methods Shackleton used to select his crew. Although they are utterly incompatible with modern HR “best practices” for hiring, Shackleton’s techniques for choosing good team members were second to none, and history has more than vindicated his approach. This is because for most people, making a hire is rarely a life or death decision — but for Shackleton, it was precisely that.

Today, we look at three counter-intuitive and paradoxical rules Shackleton lived by when recruiting men for his expedition. Whether you're looking to make new hires for your business or simply choosing which friends to keep close, Shackleton’s guide will help you surround yourself with the kind of people who never let you down…

Rule #1: Shun Results to Get Results

The heroic era of Antarctic exploration was 'heroic' because it was anachronistic before it began, its goal was as abstract as a pole, and its central figures were romantic, manly and flawed…

Its drama was moral (for it mattered not only what was done but how it was done), and its ideal was national honour…it was the site of Europe's last gasp before it tore itself apart in the Great War.

-Tom Griffiths, Slicing the Silence: Voyaging to Antarctica, p. 111

Although “exploration” was the stated purpose of most Antarctic expeditions, few explorers were able to get funding without addressing how their voyage would fuel scientific discovery. As a result, the names of the geologists, biologists, physicists and meteorologists they chose to join them played a major role in securing funds and making expeditions possible.

Shackleton, however, took a markedly different approach. Having seen how great scientists did not necessarily make for great expeditions — such as the tragic 1910 Terra Nova Expedition, in which five men lost their lives — he eschewed traditional “wisdom” for a more instinctual approach.

As historian of polar expeditions Michael Smith put it:

Shackleton’s idiosyncratic HR methods relied heavily on the personal touch. What mattered most was whether the candidate appealed to Shackleton. He once said that the four great qualities needed to be an explorer were: optimism, patience, imagination and courage.

These four qualities were what Shackleton most looked for in potential crew members. While the oft-cited newspaper ad below is likely apocryphal (the original version of it has never actually been found), it is true that Shackleton had over 5,000 men apply to join him on his 1914 expedition.

So how is it that he went about narrowing this number down to just 50?

His secret lay in flipping the common-knowledge approach on its head: instead of getting the best scientists to make a great expedition, he would instead get a great expedition to make the best scientists. To this point, Shackleton once told a fellow explorer:

Don’t saddle yourself with too much scientific work. You must decide whether you want to be a scientist or successful leader of expeditions, it is not possible to do both.

To most, this looked like Shackleton was snubbing the science altogether — and to some degree, he was. Reginald James, the physicist on the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition and the man quoted in this article’s intro, described his commander as such:

Shackleton had very little sympathy with the scientific point of view and had no idea about scientific methods.

But it was precisely by shunning results that Shackleton achieved them. He knew that while great scientists didn’t guarantee a great expedition, a great expedition would create the circumstances under which scientists could flourish — even those who were relatively underqualified.

He was more than vindicated in his approach. Ray Priestly, for example, a man with few qualifications and whose hiring story (told in the next section) is only too typical of Shackleton’s eccentric methods, later went on to become President of the Royal Geographical Society, co-founder of the Scott Polar Research Institute Cambridge, and deputy director of the British Antarctic Survey. He was also knighted for his contributions to science, as were three other men selected by Shackleton.

So how did a man with “no idea about scientific methods” end up selecting from a list of then-unknown scientists no fewer than four future knights of the realm?

The secret to it all lay in Shackleton’s next rule of hiring: knowing when, and when not, to judge by appearance…

Rule #2: Trust Your Gut

Applications were sorted into three piles: Mad, Hopeless or Possible. The Possibles might be invited to Shackleton’s London offices for a chat, though interviews were very informal and often arbitrary. There were no forms for candidates to fill in, little attention was paid to qualifications and he did not draw up shortlists.

A typical example was Leonard Hussey, a young man with impressive qualifications in fields like meteorology and anthropology. Shackleton looked him up and down, walked around the room and announced: “Yes, I like you. I’ll take you.” Shackleton elaborated a little by telling Hussey: “I thought you looked funny.”

-Historian Michael Smith

Shackleton seemed to know exactly when —and when not — to judge by appearance. His gut intuition not only helped him spot up and coming talent before others did, but it also saved him from ignoring candidates who, because of their background, would have otherwise been written off.

Today, judging by appearance is highly discouraged — but Shackleton’s story shows why it just might be the best thing you can do.