How to Become Noble

Lessons from Pope Pius XII’s speeches to the Roman nobility...

Dear lector augustus,

Let’s shake things up a bit.

As you know, my Tuesday emails are fairly straightforward. In them, I share a story from the life of an inspirational character, and provide three concrete lessons you can learn from his virtues.

But this week, I want to do something different.

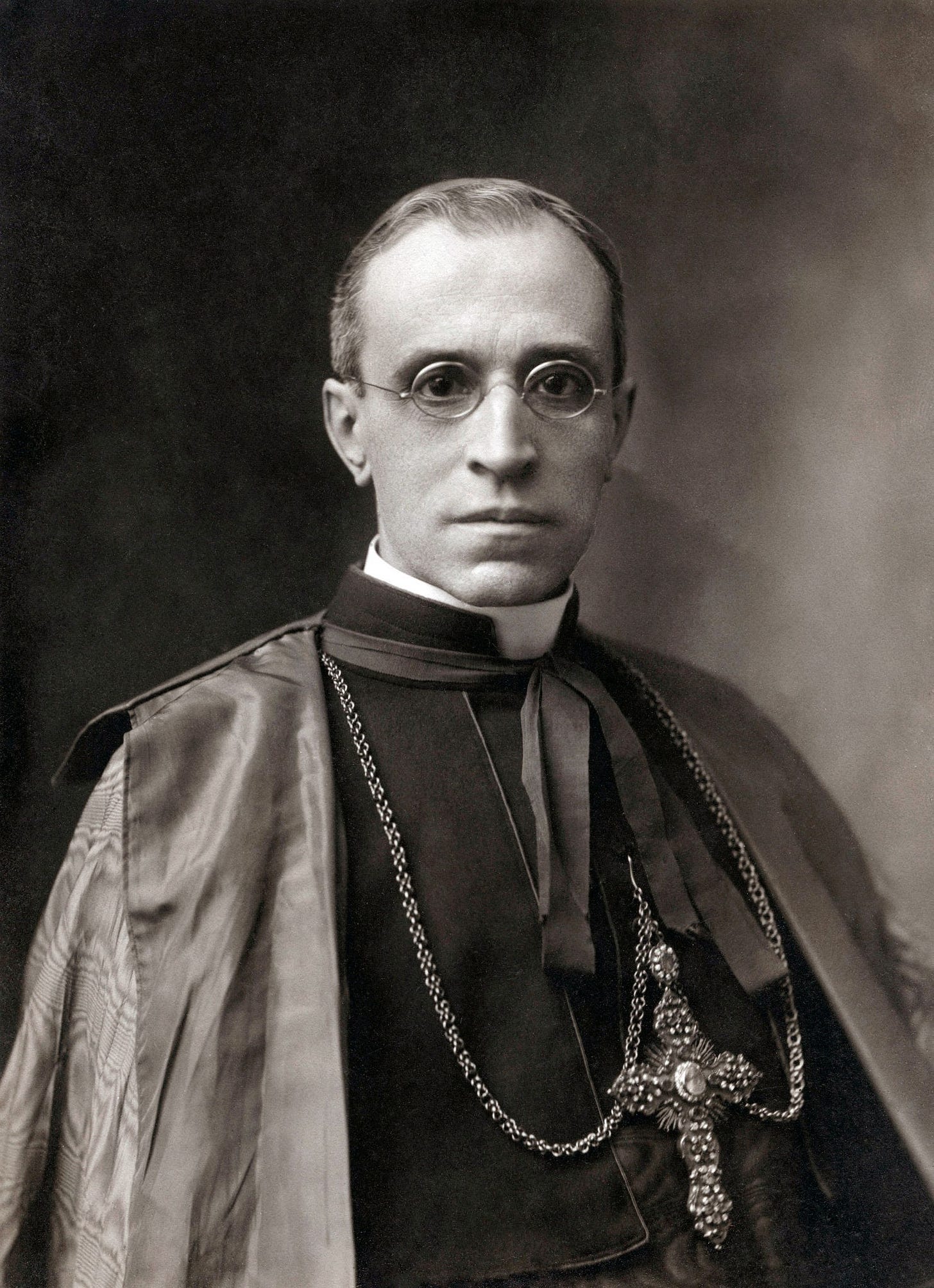

Since Conclave is scheduled to begin on Wednesday and the election of a new pope anticipated by the end of this week, I want to seize this opportunity to share a more personal story with you. It’s about one of the books that has most impacted my life, and how I believe it can inspire you as well.

The book in question is entitled Nobility and Analogous Traditional Elites, and it is the philosopher Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira’s exposition of Pope Pius XII’s speeches to the Roman nobility in the years following World War II. It provides a beautiful reflection on the role of nobility — both in title and in essence — in the rapidly changing modern world.

Today, I want to share what Pope Pius XII’s thoughts on the role of nobility can reveal to you about its essential nature, and what you can do in the here and now to become more noble — if not in title, at least in spirit.

I hope you enjoy this break from our normal cadence, and that it proves beneficial for you and your family.

-Evan

Yeast in the Dough of Society

What exactly is nobility?

Today, most people today think of nobility as a relic, as a matter of bloodlines, coats of arms, and hereditary privilege. But in his addresses to the Roman nobility, Pope Pius XII presents something far deeper — a vision of nobility rooted in Christian responsibility, moral excellence, and sacrificial leadership.

This vision can be glimpsed in one of his exhortations to the Roman patriciate:

First of all, you must maintain an irreproachable religious and moral conduct, especially within the family, and practice a healthy austerity in life.

Let the other classes be aware of the patrimony of virtues and gifts that are your own, the fruit of long family traditions: an imperturbable strength of soul, loyalty and devotion to the worthiest causes, tender and generous compassion toward the weak and the poor, a prudent and delicate manner in difficult and grave matters, and that personal prestige, almost hereditary in noble families, whereby one manages to persuade without oppressing, to sway without forcing, to conquer the minds of others, even adversaries and rivals, without humiliating them.

The use of these gifts and the exercise of religious and civic virtues are the most convincing way to respond to prejudices and suspicion, since they manifest the spirit’s inner vitality, from which spring all outward vigor and fruitful works.

-Pope Pius XII to the Roman nobility, 9 January 1958

Pay special attention to the phrase “the fruit of long family traditions” — we’ll circle back to this later.

But for now, focus on the virtues Pope Pius highlights in his address: strength of soul, loyalty, devotion, compassion, prudence, and a “delicate manner in difficult and grave matters.” The cultivation of these virtues isn’t just the privilege, but indeed the duty of the elite. The Holy Father makes this clear:

Social inequalities, while they make you stand out, also assign you certain duties toward the common good…from the highest classes great boons or great harm could come to the people.

-Pope Pius XII to the Roman nobility, 9 January 1958

Nobility, in the eyes of Pius XII, is not merely a legal class but a spiritual vocation. Its duty is to function like yeast in the dough of society — not dominating the whole, but giving it form by shaping its culture, moderating its passions, and elevating its standards.

Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira, the author of Nobility and Analogous Traditional Elites, likewise summarized the role of the nobility and warned about the dangers of disdaining it:

In a word, they are the yeast, society the dough.

To imagine that yeast is the enemy of dough because it is distinct and raises it, acting as a driving force and stimulus to elevate and increase it, is to combat progress, eviscerate evolution, paralyze life and impose boredom on everyone.

-Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira, 28 September 1993

Pope Pius XII recognized that the nobility plays a vital role in preserving the moral tone of a people. It should inspire by example, embody continuity in times of upheaval, and quietly leaven public life with dignity, courage, and faith.

But of course, most of our “elites” today do anything but — so what went wrong?

Bourgeois, or Bougie?

To answer the question of what went wrong, we must first enter the world of the bourgeoisie to investigate both its noble and vulgar undercurrents.

For many, “bourgeois” is a difficult term to pin down, as it can mean anything from the “merely wealthy” (those whose wealth is unaccompanied by virtue or cultural formation) to the middle class. Typically, it represents a kind of intermediary position held by those who are not quite noble, but not working class either.

The term also carries both a positive and a pejorative sense, and its intended meaning depends both on the background of the speaker, as well as the character of the person it describes — specifically, that person or family’s relation to tradition, virtue, and social responsibility.

Most importantly, however, “bourgeois” names not only an economic category, but a moral and cultural posture. It is used to draw a distinction between two opposing tendencies within the non-noble classes: one aspiring upward toward cultural formation and stability, the other downward toward rootless novelty and moral decay.

The latter is all too familiar, and is clearly encapsulated in the behaviour of the nouveaux riches. But it also extends to families who, even after generations of wealth, reject refinement and tradition in favor of whatever happens to be fashionable:

The pejorative sense of the term bourgeoisie is applicable to the sectors of this social category that are uninterested in forming their family traditions, or in maintaining and improving them through successive generations, and instead concentrate on pursuing the most outlandish modernity.

Even when their families have lived in opulence or easy comfort for several generations, these bourgeois still choose to resemble a group of parvenus — parvenus in a state of permanent mutation caused by their self-destructive determination not to refine their habits over time!

-Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira, Chapter VII, Section 9

This is what Corrêa de Oliveira calls the “antithetical nobility” — the modern elite who possess wealth and prominence, but no spiritual depth. He describes their behaviour in more detail:

Do these lineages constitute a new nobility?

From a strictly functional point of view, perhaps they do, but this is not the only point of view, nor even necessarily the main one. Concretely, this new “nobility” frequently is not, nor could it be, a true nobility, foremostly because a great part of its members do not wish to be noble.

In fact, egalitarian prejudices, which so many of these lineages have cultivated and flaunted since their origin, lead them to differentiate themselves progressively from the old nobility, become insensible to its prestige, and, not infrequently, downgrade it in the eyes of the world. This is done not by a forced elimination of the characteristics differentiating the old nobility from the masses, but by this new “nobility’s” ostentation of a characteristic willingly cultivated for demagogic purposes. This characteristic is vulgarity.

While the historical nobility was and wanted to be an elite, this modern antithesis of the nobility frequently prides itself in not differing from the masses. It strives to camouflage itself with the ways and habits of the masses, purportedly to escape an impending vengeance of the demagogic egalitarian spirit. This spirit is usually fanned by the mass media whose owners and top executives paradoxically often belong to this same antithetical nobility…

-Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira, Chapter VII, Section 8 (emphasis mine)

So within the bourgeoisie, there exist two contrasting groups: those who want to be truly elite (by embracing the duty and refinement true nobility entails), and those who pride themselves in “not differing from the masses.”

As for the former, these are the bourgeois families that, through discipline, memory, and a reverence for tradition, quietly mature across generations. And while they may not bear noble titles, they carry within them the very seeds of nobility itself…

The Language of Nobility

In speaking of the bourgeois society and its peculiarities, we do not intend to include those families of the bourgeoisie in whose bosom, down through the generations, flourished a genuine family tradition, rich in moral, cultural, and social values.

Contrary to the antithetical nobility, these families’ fidelity to tradition and their desire for continual improvement make them true elites.

In a social structure open to everything that enriches it with true values, these families little by little become an aristocrat-like class. They gradually and smoothly blend into the aristocracy or, by force of custom, become a new aristocracy with its own characteristics alongside the old aristocracy.

-Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira, Chapter VII, Section 9

In his 1958 speech to the Roman nobility, Pope Pius declared that “the patrimony of virtues and gifts” are “the fruit of long family traditions.” This is a concept that runs throughout his thought — the idea that it is not so much formal recognition and titles that welcome a family into the ranks of established nobility, but rather the passage of time itself.

In the above passage, Corrêa de Oliveira uses phrases such as “down through the generations” and “these families’ fidelity to tradition” to convey a similar sentiment. That is, the elevation of a bourgeois family into the ranks of nobility does not occur in a single, fixed moment — rather, it plays out over generations.

Corrêa de Oliveira goes on to explain how this use to work prior to the Great War:

The nouveau noble-nouveau riche felt ill at ease in his new social condition if he did not strive to assimilate, at least in part, its profile and manners. He rarely gained easy admittance to many of the salons. This exerted an aristocratizing pressure upon him…

Far from opposing the environment in which he was heterogeneous, then, the new noble generally strove in earnest to adapt himself to it. Above all, he did his best to give his children a genuinely aristocratic education.

These circumstances facilitated the absorption of the new elements by the old nobility to such an extent that, after one or more generations, the differences between the traditional and new nobles disappeared. The new nobles ceased to be “new” with the mere passing of time. The marriage of young nobles, bearers of historic names, to daughters or granddaughters of nouveaux riches-nouveaux nobles enabled them to avoid economic decadence and to give new luster to their coats of arms.

-Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira, Chapter VII, Section 9 (emphasis mine)

If you are familiar with my writing, you probably already know that I live in Italy, and that my wife and I are raising our son to speak both English and Italian.

As someone who has spent years learning foreign tongues, I often marvel at the fact that my children will be native speakers of both these beautiful languages. But it’s also made me ponder what it means to be truly fluent in something.

Regardless of how well you learn a foreign language, you will never be truly fluent in the same way a native speaker is. There are certain aspects of language that must be passed down, aspects which can only be learned by absorption as a child. Likewise, the nature of nobility functions in much this same way — no matter how well a father learns the “language” of nobility (virtues, culture, refinement, etc.), he is always a foreigner.

Only his progeny, by virtue of their upbringing and immersion in this language, can truly become “native speakers”. And this means the aspiring noble has a unique task laid out for him…

What This Means for You

…these families’ fidelity to tradition and their desire for continual improvement make them true elites.

Pope Pius XII, for all of his focus on the importance of time and tradition in cultivating the virtues which are “almost hereditary in noble families”, didn’t fail to recognize the value of the “analogous elites”.

These families are especially prominent in countries without formal structures of nobility, such as the United States. Yet despite their lack of history and tradition, they are still characterized by Corrêa de Oliveira as “true elites”. Specifically, these are:

…those families of the bourgeoisie in whose bosom, down through the generations, flourished a genuine family tradition, rich in moral, cultural, and social values.

Here once more, we see that phrase “down through the generations”. And this is precisely where we must focus — for it is the focal point of the aspiring noble’s calling.

Should you desire to join the ranks of these “analogous elites”, your role must be to teach your children the language of nobility. Yes, it is true that you must learn it — but that is not enough. You must also live in such a way to ensure this language will be passed down to the next generation, and then the following. Noble families are formed through time and tradition, precisely because the language of nobility can not be learned in a single generation.

And what is that language, precisely? While a proper explanation requires many more words than would be appropriate for this article, Pope Pius XII himself offers a straightforward outline that is as good as any:

1) an irreproachable religious and moral conduct, especially within the family,

2) a healthy austerity in life.

3) an imperturbable strength of soul, loyalty and devotion to the worthiest causes,

4) tender and generous compassion toward the weak and the poor,

5) a prudent and delicate manner in difficult and grave matters,

6) that personal prestige, almost hereditary in noble families, whereby one manages to persuade without oppressing, to sway without forcing, to conquer the minds of others, even adversaries and rivals, without humiliating them.

-Pope Pius XII to the Roman nobility, 9 January 1958 (formatting mine)

The Holy Father adds that the cultivation and exercise of these virtues are what “manifest the spirit’s inner vitality, from which spring all outward vigor and fruitful works”. As for the virtues themselves, they are “the fruit of long family traditions”.

Just as children must be fully immersed in the life and society of the target language to learn it fluently, so too must they be fully immersed in the life of a family that lives out these noble virtues. The task of the aspiring noble, then, is first and foremost to “maintain an irreproachable religious and moral conduct, especially within the family.”

It is an immensely difficult challenge — yet it is a worthy one.

Final Thoughts

If you enjoyed this article and would like to learn more about how to go about the task of immersing your children in the language of nobility, be sure to leave a comment to let me know.

This is quite a different article from the ones I usually write, but I can certainly envision a future in which INVICTUS shares lessons from historic families — what they did to found and cement their dynasties, and how you can imitate their example in the modern day.

In the meantime, I heartily recommend you check out fellow writer Johann Kurtz’s excellent publication Becoming Noble. He is a great resource to help you explore topics such as societal status, the value of nepotism, and raising children worthy of empires. I recently appeared on his podcast, which you can listen to below:

Lastly, premium readers of INVICTUS will get an article tomorrow about the Papal Conclave and how a pope gets elected.

Then on Saturday, we’ll send out a deep dive article about the very first Conclave in church history — why it lasted three years, and how it only ended once they decided to lock the cardinals inside…

James and I will go live on X this Thursday to discuss both of these topics with you in real time. Visit my X account at 9am ET to access the livestream — once it ends, the stream will be added to our Members-Only Video Archive for you to catch the replay.

If you’re not already a premium subscriber, please consider joining below:

Ad finem fidelis,

-Evan

This was a great dissection of what it truly means to be Noble. It also indicates that failing nobility is a problem older than I thought. Throughout the ages it can be seen in the debates between Edmund Burke and Thomas Paine and the embrace of radical chic here in the United States. Brilliant read, thank you.

The source of good virtues is Christ. One can learn them and rehearse them in life, like a habit. But, authentic conduct comes from the Souls compassion to serve which is influenced by Christ. Language at its essence is communication, although one may not be native by circumstance, being concise with words and meaning is paramount.

Lay people today strive for the label of " nobilty" or upper class in a misconstrued way. Most people are pretending to be higher classes than what they are. They are driven by Pride and have it confused as a Virtue. Appearance is an aspect of it, but it's not status. Nobility is not an example of pride, but rather the product of certain virtues passed down through families or attained. Being noble is, serving higher virtues than your own interests.