How Much Do You Need to Be Happy?

It might be more than you think...

Man shall not live by bread alone…

-Matthew 4:4

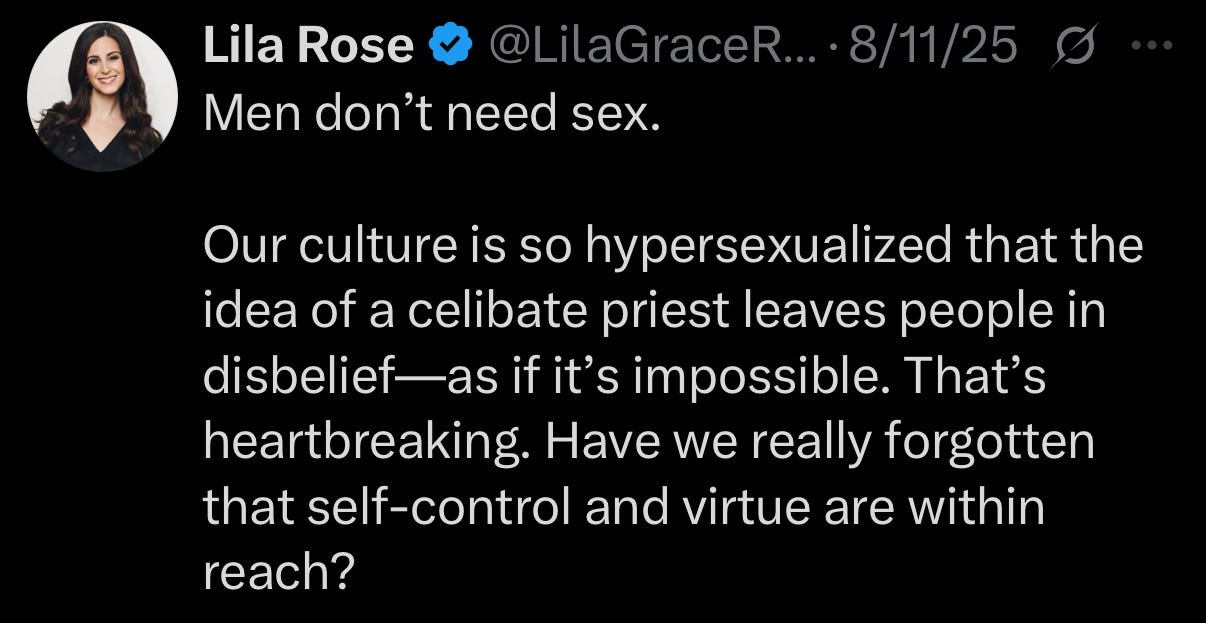

A few weeks ago, a tweet and accompanying video claiming “men don’t need sex” went viral on X. It amassed over 9 million views and 5,000 comments in just 48 hours, sparking the fires of online debate and prompting many users to express their frustration with the post’s claim.

At first glance, the post’s author Lila makes a totally logical statement: men don’t need to have sex in order to survive. So why all the outrage?

While it might be easy to assume this post went viral because of people’s conflicting opinions about the role of sex in marriage, that’s not at all the case. The real truth, which is far more interesting, is that it all came down to one word: need.

Debates over what you “need” to live well have raged since the dawn of civilization, and the question has been taken up by the Greeks, the Romans, and every great thinker since. Few, however, have ever addressed the topic quite as thoroughly — and as concisely — as William Shakespeare.

That’s why today, we turn to Shakespeare’s play The Tragedie of King Lear to see what the greatest writer in the English language can teach you about what it is that you actually need to be happy.

His answer is a surprising one: it’s both more, and less, than you think…

Air, Water, and Sex

To be clear, this article is not intended to serve as commentary on the viral post mentioned in the intro. Readers are welcome to check out the original post for themselves and make up their own minds as to its relative merit, or lack thereof.

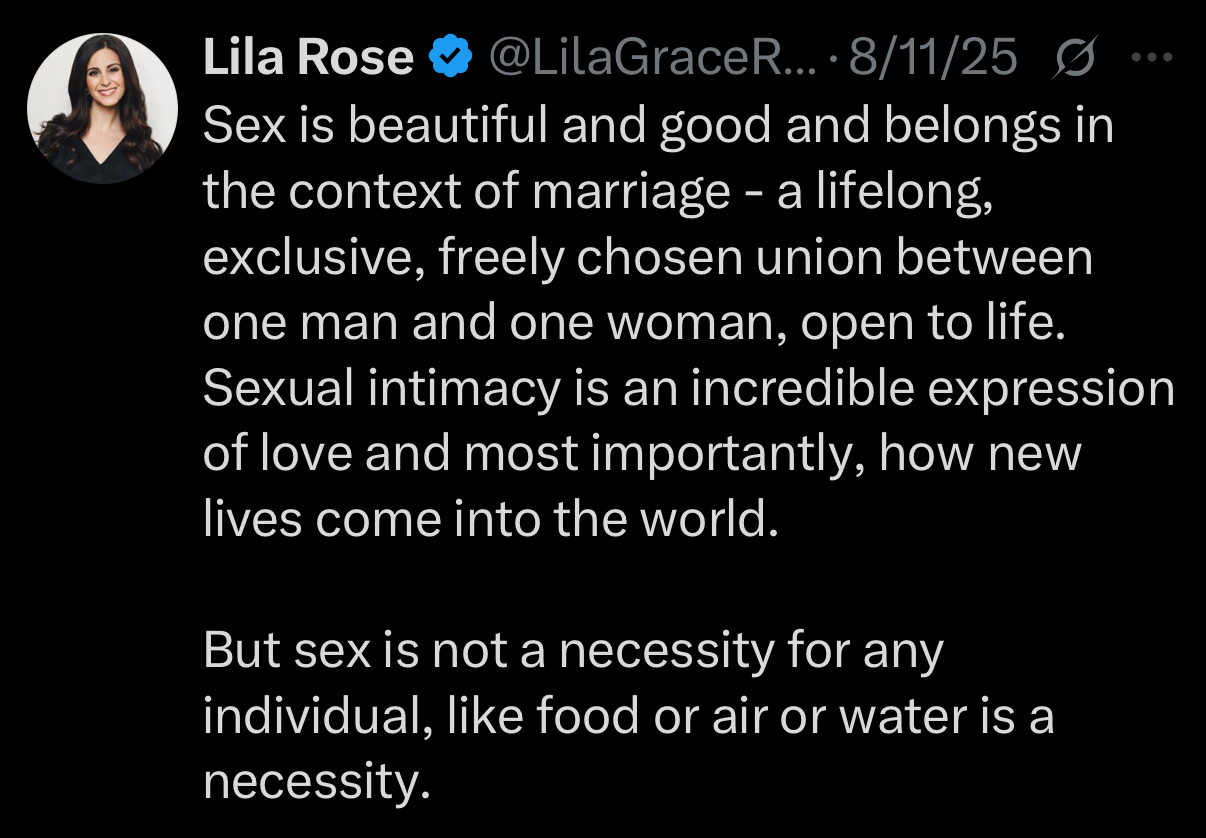

What this article will do, however, is use the post as a jumping off point to explore Shakespeare’s ideas of what humans really need to be happy. To this end, let us turn to a follow-up explanation Lila provided to her original viral post:

The key line here is the following:

But sex is not a necessity for any individual, like food or air or water is a necessity.

This is undeniably true — you will not drop dead if you don’t engage in sexual intercourse. Even if you find yourself disagreeing with the overall tone or delivery of Lila’s message, this remains an important truth to acknowledge (we’ll get to why later).

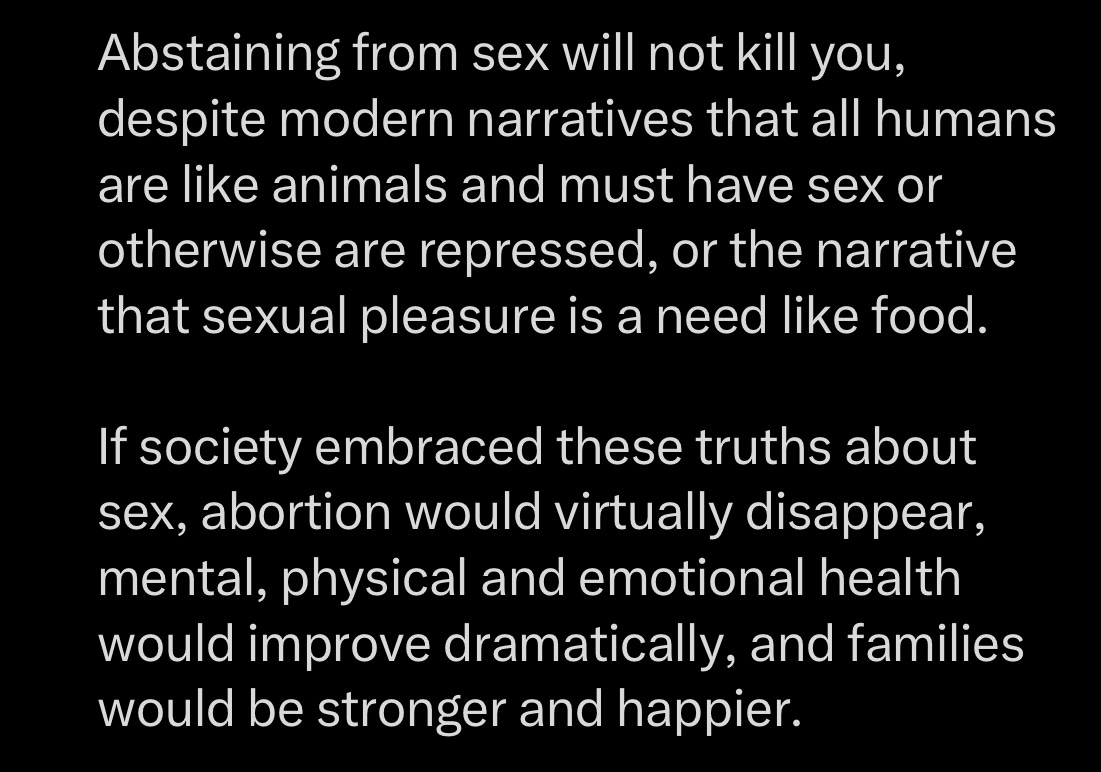

Lila then proceeds to explain why she believes that, in a hyper-sexualized society such as our own, highlighting this truth is so important:

Lila’s reasoning and intentions are good: if you remind a sex-obsessed culture that sex is not the be-all and the end-all (to borrow a phrase coined by Shakespeare), then that culture will get healthier. However, it is her framing of this idea around the concept of necessity that derails the conversation, and prompts commenters to raise their objections.

Why? Because even in Shakespeare’s time, people understood that the question of what you need is a slippery slope — one that is often used to justify taking everything from you.

Nowhere is this better exemplified than in King Lear’s conversation with his daughters, which we look at now…

Reason Not the Need!

Our basest beggars/

Are in the poorest thing superfluous.

-King Lear, Act II, Scene 4

Shakespeare’s King Lear begins with its eponymous main character deciding to retire early. He resolves to split his kingdom amongst his three daughters, dividing it up based on the praise he receives from each one.

The first two daughters, Regan and Goneril, go along with their father’s game and heap praises upon him. But the third, Cordelia, refuses to flatter her father — she simply says that she loves him with the normal degree of filial piety she ought to:

I cannot heave

My heart into my mouth. I love your majesty

According to my bond; no more nor less.

-King Lear, Act I, Scene 1

Furious, Lear banishes Cordelia, cuts her out of the inheritance, and divides his kingdom between Regan, Goneril, and their husbands. His only caveat before setting aside the crown for good is that he still wants to keep a “reservation of an hundred knights”. These will accompany him to the homes of Regan and Goneril, where he intends to live out the rest of his days.

But the problem is, Lear’s knights cost money to maintain. And now that Regan and Goneril hold the keys to power, they scheme to deprive their father of his expensive retinue. Slowly whittling down his numbers, they force him to go from 100 knights to 50, then from 50 to 25, and from 25 to 10.

Finally, when Regan asks why Lear even needs one knight, the disgraced king launches into his famous retort:

O, reason not the need! Our basest beggars

Are in the poorest thing superfluous.

Allow not nature more than nature needs,

Man's life is cheap as beast's.

-King Lear, Act II, Scene 4

These four lines open the door to Shakespeare’s understanding of what you really “need” in life. We’ll now look at them line by line:

O, reason not the need!

Here, Lear uses “reason” not as a noun but as a verb, essentially saying “don’t question the need!” Instead of replying to Regan’s question, he rejects it outright, refusing to dignify it by offering a justification as to why he “needs” a knightly retinue (we’ll come back to this shortly). He then continues with the next two lines:

Our basest beggars

Are in the poorest thing superfluous.

This is a focal point of Lear’s argument: that even the poorest among us, “our basest beggars” still have more than what they need to physically survive. The tiny dog the homeless man keeps for company is “superfluous” in that it is unnecessary and more than enough. So too, one could argue, is the ratty sleeping bag he keeps by the dumpster — does he really need that to survive? Especially since the beggars a few blocks down get by without any blankets at all?

It all culminates with Lear’s final declaration:

Allow not nature more than nature needs,

Man's life is cheap as beast's.

The conclusion of Lear’s reasoning is that if human beings are permitted only what they strictly require to survive, then they are reduced to the state of beasts. But while animals are made to survive, humans are made to live — and living life necessarily entails building and enjoying that which goes beyond the narrow limitations of pure need.

This is why Lear begins his retort by refusing to answer Regan’s question about why he needs even one knight, because to provide a justification is to have already lost the argument. Rather, he shows why the entire premise of the question is flawed, for even “Our basest beggars / Are in the poorest thing superfluous.” Questioning the need for superfluity, he posits, only results in a race to the bottom — a race in which the inevitable outcome is man’s degradation to the state of beasts.

Through the character of King Lear, Shakespeare posits that in order to truly live, you need more than what is merely required for your physical survival. But what exactly does that entail?

Hints in the lead-up to Lear’s outburst reveal three main things Shakespeare suggests you need to live a life that’s meaningful…