"Thank God I have done my duty" — Horatio Nelson & Heroism

The life of the most famous sea lord in modern Western history speaks of a heroism that endures precisely because it flies in the face of modernism.

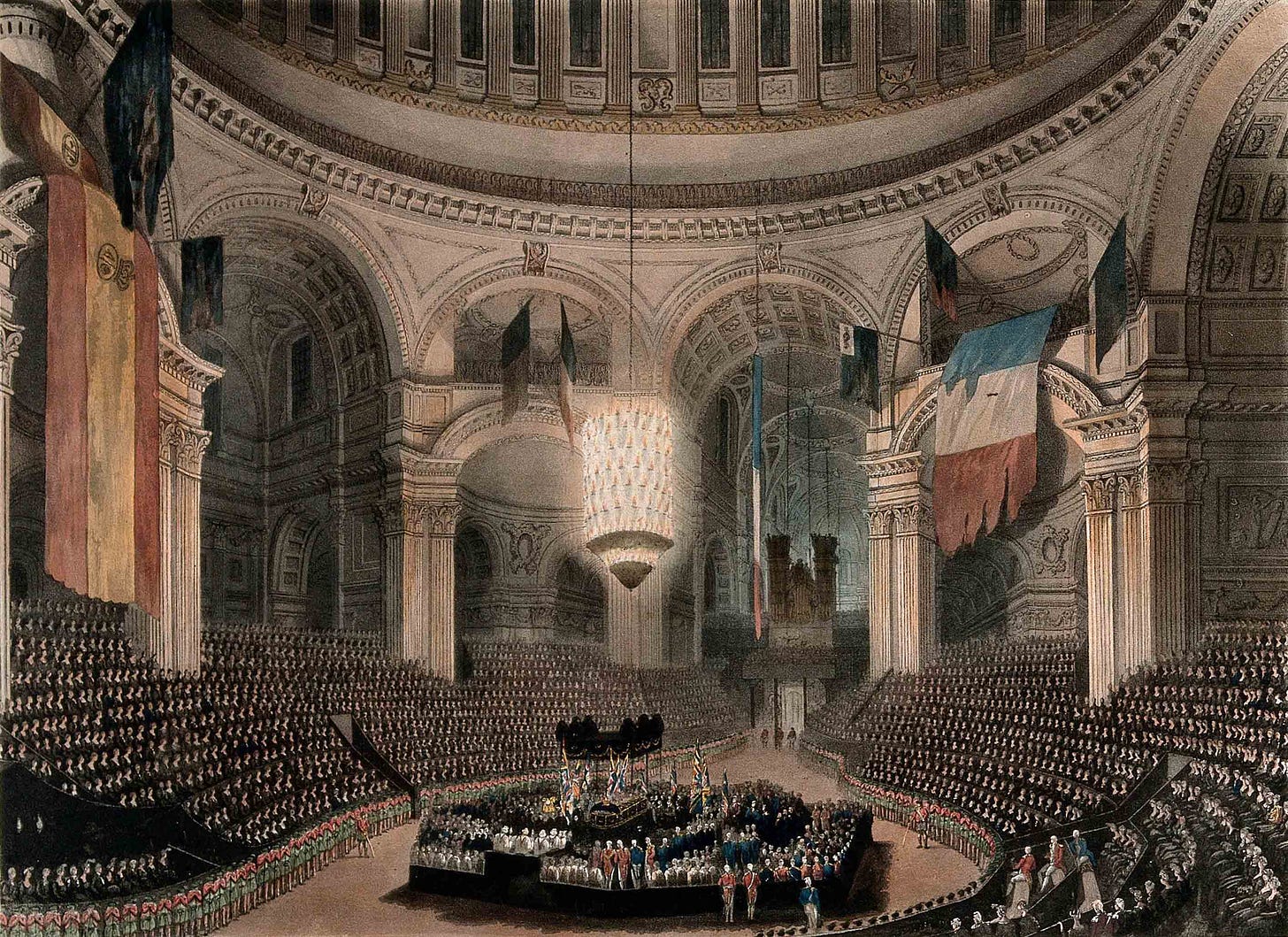

199 years ago today, on the 9th January 1806, almost 10,000 troops marched through the heart of London. Many thousands more lined the way, as all Britain grieved the passage of a hero the likes of which nations see only a handful of times in a millennium.

So vast was the procession which bore the body of Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson, conqueror of the Nile and Trafalgar, that when the head of it all reached the threshold of St. Paul’s Cathedral, the rear had yet to depart the Admiralty in Whitehall, over a mile away to the west.

Nelson, who had delivered triumph at the cost of his life, inspired such bittersweet pain in the breast of every Englishman by his death that the glory of Trafalgar would never truly eclipse its grief. The Times, the newspaper of Britain’s record, would echo that dread imbalance:

“We know not whether we should mourn or rejoice. The country has gained the most splendid and decisive Victory that has ever graced the naval annals of England; but it has been dearly purchased”

The Times, 6th November 1805

Yet King George III himself, moved to tears by the tidings from the Mediterranean, would venture a step further — "We have lost more than we have gained".

This is the story of what was truly lost that day.

From the Rectory to the Roof of the World

It is both curious and entirely appropriate that the life of so transcendent a hero should begin in holiness. For Horatio Nelson was born on the 29th September 1758 in the rectory of the Norfolk village of Burnham Thorpe, as the sixth of the eleven children of the Reverend Edmund Nelson and Catherine Suckling. Faith, indeed, would define much of the life of a boy who would one day mature into one of the greatest foes of the French Revolution.

In his more earthly aspirations however, Horatio would turn to one Maurice Suckling, his maternal uncle and a decorated naval officer who had seen action in many of the century’s grandest conflicts. The allure of the waves and awe at the captain’s stories would have stirred the heart of any young boy. But this was not any young boy, and the late 18th century presented fewer barriers to the wild dreams of the most determined of boys.

Nelson indeed was not even a teenager when he decided to follow his uncle and enlist in the King’s navy. Suckling, while obliging, was however rather skeptical of the prospects of the sickly twelve year old Horatio, writing in a letter to the boy’s father:

“What has poor Horatio done, who is so weak, that he, above all the rest, should be sent to rough it out at sea? But let him come; and the first time we go into action, a cannon-ball may knock off his head, and provide for him at once”

Captain Maurice Suckling, on his nephew Horatio Nelson

Thus on New Year’s Day 1771, young Horatio reported to the deck of HMS Raisonnable, where he cut a figure so unassuming that it was not until the second day that any thought to offer him food or lodging. Nevertheless, Suckling rapidly raised him to the rank of midshipman, the lowest rung of officer.

Ironically, England’s greatest seaman soon discovered he suffered from an ailment that would plague him until the day he died — seasickness. Yet while fighting the motion of the waves and bemusement of his elder colleagues, few could have imagined that Horatio would one day be the image of personal bravery.

When the Raisonnable was stood down as tensions with Spain dissipated, Horatio was soon reassigned to the Mary Ann, a cargo-laden Indiaman bound for the Caribbean, so as to garner his first true experience of the sea. “I returned a practical seaman”, Nelson recalled of it, though “with a horror of the Royal Navy”.

Escorting merchant wares was hardly the enterprise of heroes. Fortunately, more adventurous offerings were soon to present themselves. In 1773, Captain Constantine Phipps was tasked with leading an expedition to seek out the fabled North East Passage, by which India might one day be reached by skirting Russia in place of Africa. Upon hearing of this, Horatio knew at once that he had to be a part of it.

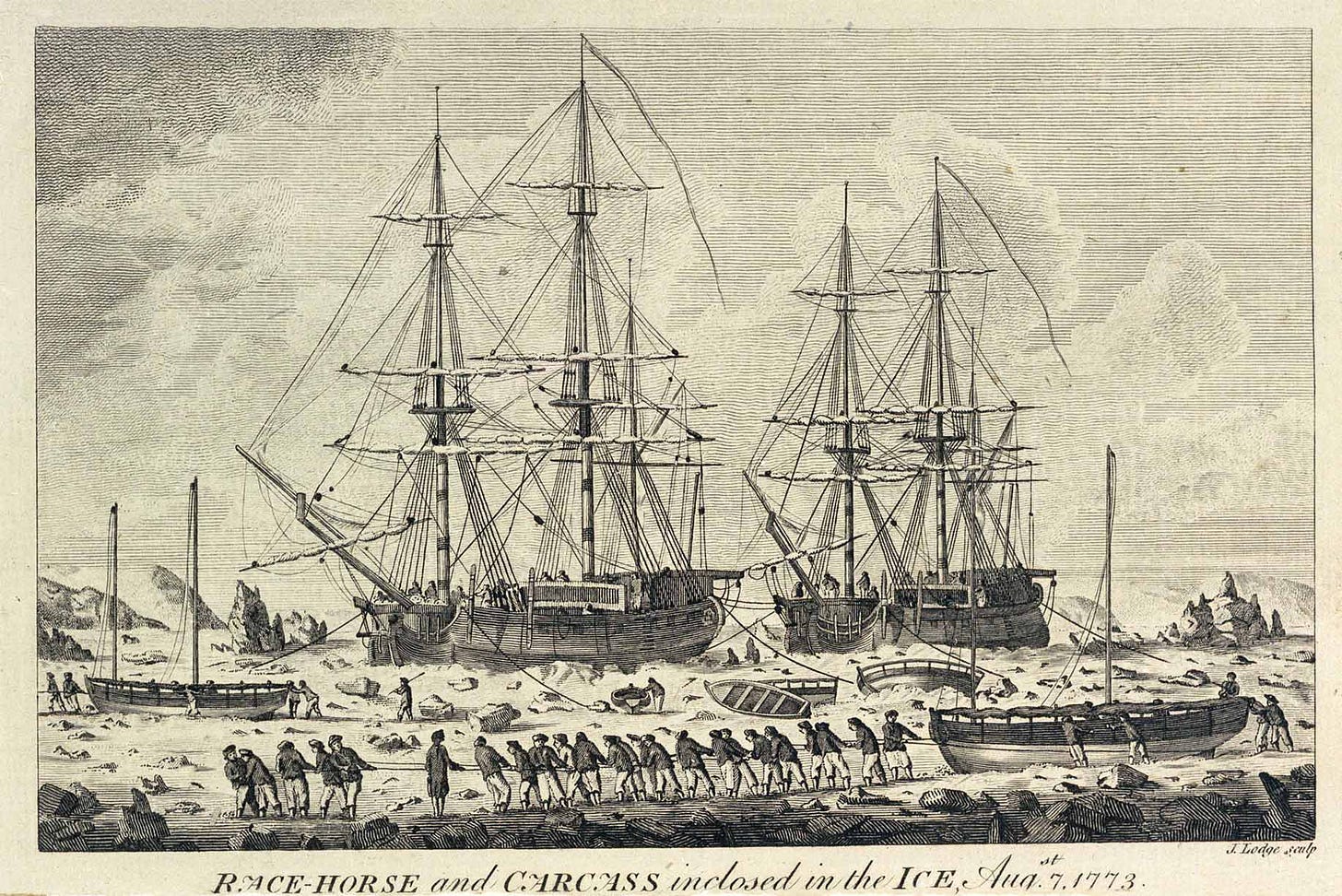

Soon after, Suckling arranged for him to be attached to one of the two vessels chosen for the expedition, HMS Carcass, as a coxswain (navigator) to Commander Skeffington Lutwidge. At fifteen, Horatio Nelson had already crossed the Atlantic twice, and was now bound for the Arctic Circle.

Dicing with Death

Departing the Deptford docks in June 1773, HMS Racehorse and Carcass passed the rough coasts of Norway and entered the icy waters of the far north. Alas it would not be long before the two bomb vessels, chosen precisely for their hull strength, would find their passage frustrated by the mountainous ice fields of the Arctic.

Just ten degrees from the North Pole, the expedition became immobilized by its frozen halo. It was here than young Nelson would have his first, modest taste of command, upon being ordered to lead a small four-oared cutter from the Carcass to bear help to the crew of the Racehorse.

A team of the latter, having spied an opening in the ice, had resolved to hunt for Arctic game. In doing so, however, they chanced upon a particularly large walrus — which responded with great indignation to the gunshot fired into its face.

Scarcely even wounded, it dived beneath the dark water, only to promptly return with reinforcements, who proceeded to besiege the Racehorse launch. Only the sudden arrival of Nelson, and the fear of yet more humans in the area, convinced the beasts to withdraw.

Not long after, Britain was almost robbed of her hero when, upon sighting a polar bear yonder, Horatio and a beleaguered companion gave chase across the ice. When close, Nelson leveled his musket and prepared to fire. Unfortunately, the rusty weapon misfired with a flash in the pan, promptly reversing the odds of the situation. Unperturbed, young Horatio inverted the weapon and valiantly attempted to club the bellowing beast. Only a sudden cracking of the ice between boy and bear, along with a blast of cannon from the Carcass, now aware and aghast, saved Horatio Nelson from an inglorious end.

Upon being berated by Lutwidge for his irresponsibility, the young Nelson defended his deed with "I wished, Sir, to get the skin for my father”, in an episode his superior would, decades later, recount with much mirth.

Privateers of the Caribbean

The dangers of Nature would be enhanced by those of Man when Nelson, following the forced return of the expedition, renounced the cold in place of heat, and embarked for India. Thanks to the ever guiding hand of Suckling pulling strings in the Admiralty, Horatio was appointed to HMS Seahorse just in time for the eruption of the Anglo-Maratha war in early 1775.

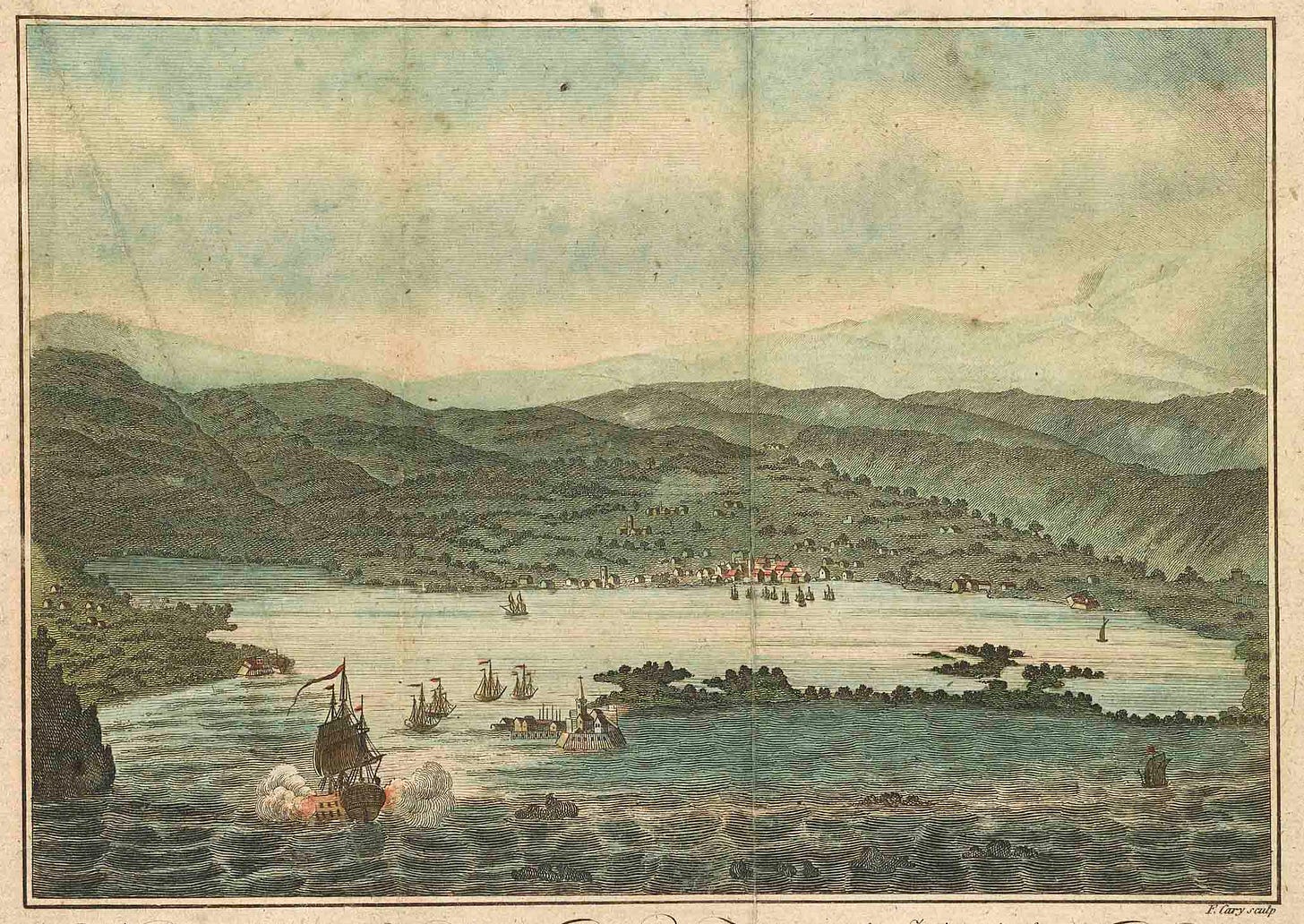

Aiding a convoy of the East India Company, Nelson would experience his first combat at sea on the 19th February, when a flotilla of the Sultan of Mysore fired upon them en route to Bombay. An exchange of weaponry swiftly repelled the attack, though far more harrowing for the seventeen year old Horatio was the malaria he contracted in the aftermath, and which he battled all the way aboard the six month voyage back to Britain.

Not one to lay idle when immortality beckoned, in 1777 Nelson, having passed his lieutenant’s examination, was dispatched once more to the West Indies, though this time in more perilous circumstances. For with the revolt of the American colonies now a military operation, in place of protecting vessels Nelson was charged with hunting them, seeking out American privateers and supply vessels in the Atlantic. That same year, after capturing the merchantman Little Lucy, Nelson was rewarded by his first independent command, of the very ship now in his possession.

After many a merry month chasing prizes around Hispaniola, Nelson’s superior, Captain William Locker, assigned him to HMS Bristol, flagship of Commander-in-Chief Sir Peter Parker. With France by now a fully-fledged belligerent in the American war, the Caribbean grew richer still with targets for the Royal Navy.

By 1778, Nelson had amassed prize earnings of as much as £400 (possibly more than half a million sterling by today’s purchasing power). Wealthy and daring, Nelson was nurturing the respect of his peers and superiors alike, such that when his uncle and patron, Maurice Suckling, by then Comptroller of the Navy, died in July, his career faced no danger.

The Nicaragua Disaster

In 1779, just shy of his 21st birthday, Horatio Nelson was promoted to Post-Captain and given command of the 28-gun HMS Hinchinbrook. It was a command that almost killed him, when he was ordered to the wildly ambitious and poorly thought-through British attempt to seize the southern colonies of Spain — her too having now entered the war — in the Americas.

The orders of Nelson, to cut Spanish America in half, were daunting, and the San Juan Expedition was an operational fiasco. Long before reaching Lake Nicaragua, the British force was decimated by a lethal concoction of tropical diseases, in an embarrassment alleviated by but a single moment of glory.

Despite being starved of ammunition and supplies, after a two-week siege Nelson and his emaciated men successfully stormed the fort de la Inmaculada Concepción on the banks of the San Juan river. With over 2,500 men perishing to sickness however, it was an entirely Pyrrhic victory — made all the clearer by Nelson himself contracting yellow fever, forcing his evacuation to Jamaica.

His slight build however would be deceptive, as Nelson escaped death once again, aided by the nursing skills of Cubah Cornwallis, the servant and possibly lover of the brother of Lord Charles Cornwallis, whose surrender at Yorktown three years later would famously conclude the war in favour of the American alliance.

Peace and Revolution

The cessation of hostilities would however plunge Nelson into the tedium of peacetime. Among the many gains from the Americas he bore home to Britain was one he would most certainly regret later in life — his wife.

Francis ‘Fanny’ Nisbet, a daughter of a well-to-do plantation family on the island of Nevis, was a widow when Nelson first met her. The whirlwind romance would begin to strain soon after their marriage in 1787, for Fanny was accustomed to the warmth of the Caribbean and luxury of life it offered. Dutiful she remained however, with the death knell of their bond coming years later from the greatest of her husband’s sins — his infatuation for Lady Emma Hamilton, the wife of Sir William Hamilton, British Ambassador to the Kingdom of Naples.

Domestic life, ultimately, seldom had a place in the heart of an adventurer, and when the armies of Revolutionary France overran the Austrian Netherlands in 1792, exposing the British coast to attack, Nelson was likely among the few to be more excited than anxious when war broke out the following year.

Nelson not only desired, but needed command, and the Admiralty, needing commanders, readily gave it. Appointed to the 64-gun HMS Agamemnon, Nelson embarked for the war that would seal his name for eternity in the annals of history. Fired by his disgust at the bloodthirsty revolution in Paris, he thus roused the crew at the Chatham docks:

“There are three things, young gentleman which you are constantly to bear in mind: Firstly you must always implicitly obey orders, without attempting to form any opinion of your own respecting their propriety. Secondly, you must consider every man your enemy who speaks ill of your King; and thirdly you must hate a Frenchman as you hate the devil”

Horatio Nelson to the crew of HMS Agamemnon, January 1793

No longer fighting in the distant Americas, but for the destiny of Europa herself, Nelson, and the Agamemnon, would depart in haste. As the deplorable conduct of the junta in Paris grew ever more violent to Man and apostatic to God, revolts erupted across the violated body of the former Kingdom of France.

The city of Toulon on the Mediterranean Coast indeed saw royalist and moderate republican alike join forces to resist the ‘National Convention’, and it was to their aid that the Royal Navy rushed in the summer of 1793.

War in the Mediterranean

As the squadrons of Admiral William Hotham, to whom Nelson now answered, joined with those of Lord Samuel Hood, Commander-in-Chief of the Mediterranean Fleet, it soon became apparent that their numbers were insufficient to quell the vast host that bore down on Toulon.

Nelson was thus ordered to procure reinforcements from Italian allies, initially from Sardinia but more crucially from King Ferdinand IV & III of Naples and Sicily. It was there, at the seat of the Bourbon monarchy of Italy, that Nelson would at last meet Sir William Hamilton, the man he would repeatedly cuckold, and his wife Lady Emma.

“Thus that acquaintance began which ended in the destruction of Nelson's domestic happiness”, as Robert Southey put it. Nevertheless, the negotiations bore fruit, and the King fatefully agreed to aid the British.

It was on this mission too that Nelson saw his first action of the war. Spying enemy vessels just off the coast of Sardinia, on the 22nd October Nelson ordered the Agamemnon to pounce upon the French Melpomene. To her was dealt considerable damage, before the arrival of the rest of the squadron forced Nelson to withdraw. Toulon, alas, would capitulate soon after, leaving the Coalition in dire need of a Mediterranean base.

In Corsica, the Royal Navy saw potential, and spent much of early 1794 sieging it down. Yet Nelson’s frustration at the slow pace of operations at Bastia would give way to a brutal confrontation with his mortality at Calvi.

While supervising the British guns trained on the city on the 12th July, the deadly efficacy of French counter battery fire would see a shot strike the revetment directly in front of him, sending a shower of stones and debris directly into his path. The incident cost Nelson his right eye, though more to his annoyance than despair. Bandaged up, he quickly returned to the fray, and the management of the British victory.

There are limits to what a mid-ranking officer can do, however, in the face of armed nations. The aggressive manoeuvres of Nelson at the subsequent Battle of Genoa were undermined by the timidity of Admiral Hotham, and the sheer weight of French armies descending upon Italy soon compelled the British to evacuate the entire theatre.

The arrival of the more competent Admiral Sir John Jervis failed to reverse the situation, and following the defection of Genoa to the French, the enraged Nelson was forced to evacuate the island that he had expended an eye to conquer. Thankfully, he would soon have the opportunity to vent that anger.

A National Hero

With the Agamemnon returned to Britain for repairs, Nelson entered 1797 in command of HMS Captain, at a time when the danger of a French invasion of Britain was growing.

With Spain now fighting alongside Paris, it was imperative to prevent the navies of both from uniting in the English Channel. To this end, Nelson joined Admiral Jervis near the gates to the Mediterranean, where on the 14th February both turned to engage the Spanish armada off the coast of Cape St. Vincent.

In a battle dominated by both sides being unaware of the other’s true strength, it was here that Nelson demonstrated one of his most noteworthy qualities — knowing when to follow orders, and when, after acquiring knowledge that others lack, to disregard them.

Breaking formation, with a cry of "Westminster Abbey or Glorious Victory!”, Nelson personally led the boarding actions that would seize two enemy vessels in quick succession, and carry the day for the Royal Navy (for a more complete analysis of the battle, see here).

Jervis, made the Earl St. Vincent in the wake of the victory, was fully aware that Nelson had defied his command, but had the humility and magnanimity to recognize the wisdom of his doing so, and did not reprimand him. Nelson, for his actions, was knighted as a member of the Order of the Bath, and soon after promoted to Rear Admiral, as his name began to emerge from the corridors of the Admiralty to the streets of Britain.

Ironically, the immediate aftermath would see the humbling of this glory. A failed attack on the Spanish port of Cádiz in June would deny the British a knockout blow that Cape St. Vincent had otherwise permitted. Only the valour of his coxswain would spare Nelson from death in the action.

Then a month later, the new Rear Admiral would meet with arguably his greatest military failure, when a confused assault on Santa Cruz de Tenerife saw Nelson take a musket ball to the right arm moments after landing. Never one to take defeat without defiance however, Nelson managed to scale the side of HMS Theseus with his working arm, legs and willpower, seeking out the surgeon himself once on the deck. Barely half an hour elapsed between the amputation of his arm and his impatient return to duty.

Thus while the battle would be a military debacle, the reputation of Nelson emerged unscathed, and he was soon after granted command of HMS Vanguard.

Triumph in the Orient

Steeled by humbling defeats, and the growing toll of war upon his own body, 1798 would mark the transformation of Horatio Nelson from man to myth, as his stratagems shaped not only the course of battles but of history itself.

Made aware of the movement of Napoleon Bonaparte, in the summer Nelson veered east to head off his as yet unclear intentions. Suspecting an attack on Egypt, he discovered a strangely peaceful port of Alexandria on the 28th June. Puzzled, he departed.

Unknowingly however, he had actually beaten Bonaparte to it, with the future emperor docking just 24 hours later. Realizing what had occurred, Nelson circled around for the reckoning.

Since Alexandria’s harbour was inadequate for the French fleet, they had anchored in Aboukir Bay, some twenty miles to the northeast. Taking off in pursuit, Nelson, sensing death or glory in what was to come, declared before his officers, "Before this time tomorrow, I shall have gained a peerage or Westminster Abbey”.

His opposite number, French Admiral François-Paul Brueys d'Aigalliers, commanded an apparently enviable position of defence, his fleet deployed close to the shoals to shield their port side. Unfortunately for them, Captain Thomas Foley, Nelson’s perceptive Welsh officer, realized that they were not positioned close enough.

As a result, the swiftly flanked French line was subjected to a withering array of broadsides they could mount only half a defense to. Fierce indeed was the Battle of the Nile, as Nelson himself was struck by shot on the deck of the Vanguard, causing copious blood loss and a flap of torn skin to obscure his eye, which the surgeon promptly stitched back.

The breathtaking centrepiece of it all, however, came at roughly 22:00, when relentless British barrages caused the powder magazine of Bruey’s flagship, L’Orient, to catch fire, resulting in an explosion so powerful that vast pieces of the hull were blasted over the masts of nearby ships, as Englishman and Frenchmen alike stopped to witness the lethal spectacle.

11 French ships of the line were captured or destroyed, without the loss of a single British vessel. As the first major victory where Nelson had been in complete command of a fleet, the Nile would cement his legend.

Ennobled as Baron Nelson of the Nile and Burnham Thorpe, he acquired a dazzling array of decorations, though none more luxurious than the çelenk, or diamond plume, gifted by a grateful Sultan Selim III. For in stranding Bonaparte in Egypt, he had saved the Ottoman Empire further ignominy in the Middle East.

“He looks more like a Prince of the Opera than the Conqueror of the Nile”, remarked General Sir John Moore in words that would prove rather accurate, for Nelson proved ever more difficult for the Admiralty to deal with on land.

Selectively following orders from London, he would sub-designate many of them to junior officers, while his ‘aggressive advice’ to King Ferdinand would backfire spectacularly when the French marched upon Naples in 1799, triggering over a decade of turmoil in the Italian South. Nevertheless, his aid in overthrowing the French puppet republic in Naples would earn him the Dukedom of Bronte from Ferdinand, a title Nelson signed his name with throughout his few remaining years.

Yet his escapades in Naples with Lady Hamilton would prove ever more scandalous, and are likely the reason why he had been granted a mere barony over a higher rank of nobility. By Christmas 1800, his marriage to Fanny had collapsed completely, when following her ultimatum, he replied, “I love you sincerely but I cannot forget my obligations to Lady Hamilton or speak of her otherwise than with affection and admiration”.

There was only one avenue to redemption for Horatio Nelson.