The Crucible of Rome's Greatness

The ultimate nemesis of Ancient Rome held the fate of the West in the palm of his hand. By brilliance, he almost took it. By hesitation, he lost it.

Seldom has there been a struggle of Man against his propensity for evil quite like the total war that erupted between Carthage and Rome in 218 BC. For over the course of seventeen savage years, as the casualties reached the hundreds of thousands, the rules of civilised war frayed before the desperation of two superpowers that had everything to gain, and everything to lose.

The audacity of Hannibal would bring Rome to her knees. Yet this, and one fateful decision, would see him unwittingly make of the Eternal City a foe more ruthless than any the world had yet seen…

The Oath of Vengeance

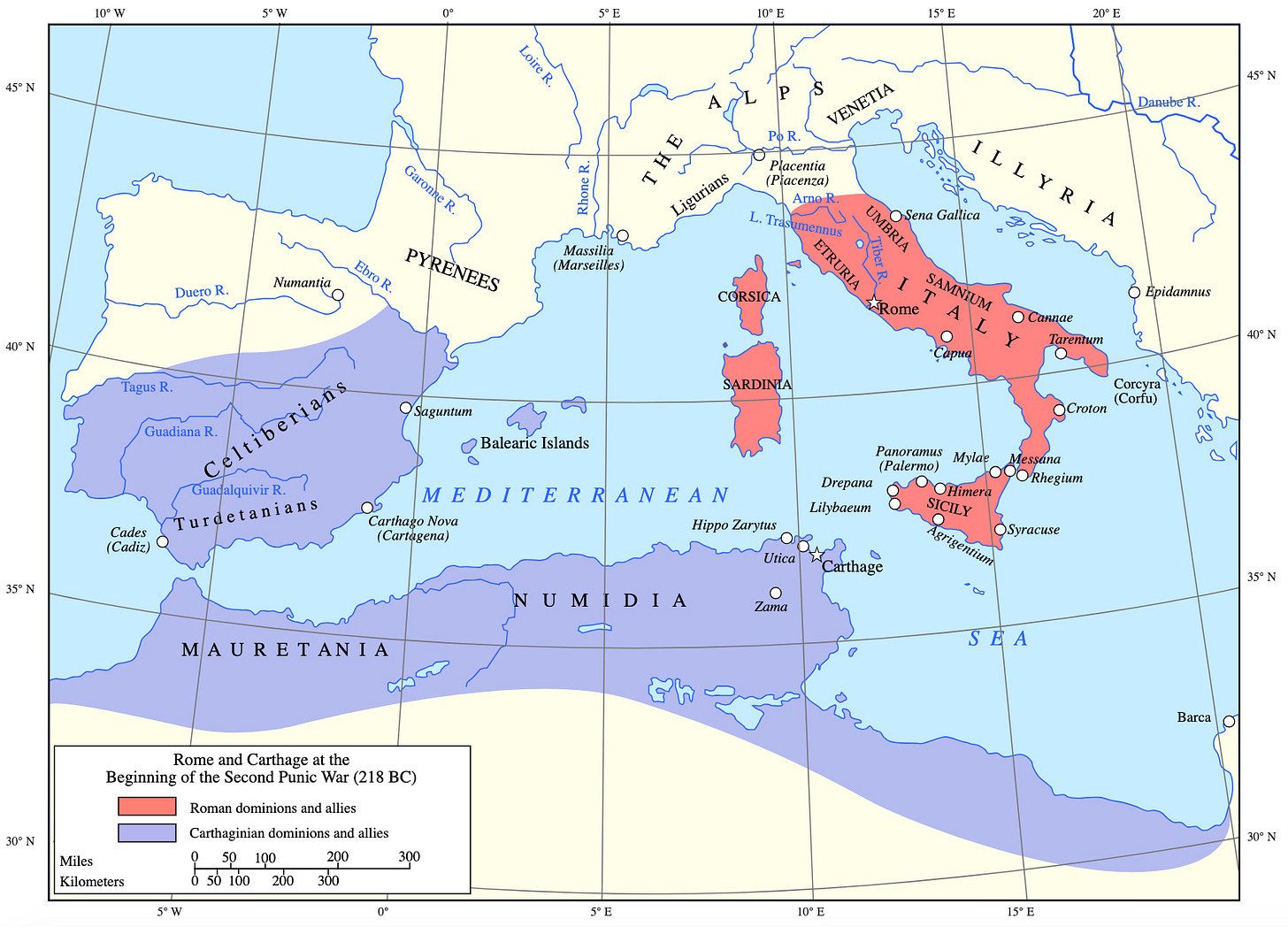

As the 3rd century BC approached its close, many could have been forgiven for believing the fortunes of the known world to be a settled matter. For in 241 BC, twenty three years of war on land and at sea had seen Rome wrest supremacy of Western Mediterranean from Carthage, along with much of the island of Sicily, the gateway between Europe and Africa.

Yet defeat turned to humiliation for Carthage, when some twenty thousand mercenaries who had fought for her, angered at their absent payment, rose in revolt in Africa, Sardinia and Corsica. Taking advantage of the chaos that resulted, in 238 BC Rome violated the Treaty of Lutatius, exploited Carthaginian weakness and promptly seized both of the northern islands.

One of the few commanders in Carthage to emerge from this debacle with their reputation intact was the charismatic general and fearsome patriot Hamilcar, called ‘Barca’ (‘The Thunderbolt’). Unable to bear the shame into which his country had fallen, Hamilcar brought his son before a holy altar. There the nine year old Hannibal, hitherto innocent, swore before his father and the Canaanite gods an oath of vengeance, that he would by his life prove to be the enemy implacable of the Roman people. In that moment, the bane of the Eternal City was baptised, and the Mediterranean die was cast.

Preparing the Ground

Over the remaining years of Hannibal’s youth, he would bear witness to his father’s extraordinary crusade to compensate the disaster of the First Punic War by carving out a new empire in Hispania. This Hamilcar achieved with such success that upon his death in 228 BC, and the assassination of his chief lieutenant Hasdrubal seven years later, the loyalty of the Carthaginian armies in Spain passed willingly to Hannibal, who in demeanour and visage, appeared the image of his father.

Twenty six years of age, and already a veteran of war, Hannibal moved at once to secure Spain in preparation for an attack on Italy. One by one, the strongholds of Iberia fell, before he turned his sights to the powder keg that would ignite the war he had been born for — the city of Saguntum.

For several years, the boundary of Roman and Carthaginian interests in Spain had been fixed by treaty at the Ebro River. Yet Rome soon after allied herself with Saguntum, which lay well to the river’s south, in a move widely seen in Carthage as yet another betrayal of diplomacy by her rival. Hannibal knew, therefore, that if he were to force the situation himself, he could be assured that any opposition on the home front would be lukewarm.

So indeed it would be, when in 219 BC Hannibal invested the city, triggering the great crisis. The siege was be a grueling affair, in which Hannibal himself was wounded. But when Saguntum at last capitulated eight months later, the spoils were such that he could both richly reward his men and beguile Carthage. The true prize for Hannibal, however, was what followed — when an incensed Rome declared war on Carthage.

Breaching the Gates of Italy

Events would move quickly. Rome, believing that the Second Punic War would be a repeat of the first, mobilised to defend Sicily. Yet Hannibal was far too cunning and visionary to be guided by convention.

Amassing 90,000 infantry, 12,000 cavalry and as many as 40 war elephants, Hannibal activated a plan long in the making that quite literally bypassed the entire Mediterranean theatre. Marching not south, but north from Spain, the great host crossed the Pyrenees into the geopolitical no-man’s land of Gaul, to launch an invasion of Italy from her stone crown - the Alps.

To say that the journey was perilous would be an injustice, and not merely due to Nature. For the Second Punic War was defined not merely by the battlefield engagements of Rome and Carthage, but by the exhaustive attempts of both to seek allies abroad, while stripping away those of their foes.

By a delicate balance of flattery, gifts and shows of force, Hannibal cowed the Gallic tribes. Those who aided him, he rewarded, and those who sought to frustrate him, he swept aside, before offering all the chance to avenge the defeats Rome had meted out to them over the decades prior.

The Roman Consul Publius Cornelius Scipio, assigned to Spain, was shocked to learn that Hannibal was no longer there. So too when he landed at Massilia (modern-day Marseille), finding the Carthaginian camp already abandoned. One of the few to realise the impending danger, he withdrew at once to northern Italy, whose threadbare Roman garrison was reeling from a violent uprising by the Boii tribes.

Hannibal, meanwhile, contested Mother Nature herself, as he embarked on the enterprise which would earn him the disbelief of contemporaries, and immortality of history — the crossing of the Alps.

Battling unstable paths, the ambushes of the mountain peoples and the dense snow drifts, the Carthaginians drew on every ounce of courage and determination to cross the peaks. Random attacks, sudden rock falls and sheer drops would whittle away at their numbers, yet by the force of Hannibal’s will, fifteen days of the Alpine gauntlet would see the elephants of Africa set foot on Italian soil. Yet the toll was heavy — the Carthaginian army was less than half what it had been in Spain, and winter was coming.

The Humbling of Rome

Consul Scipio sensed weakness, remarking of the Carthaginian host “they are but the resemblances, nay, are rather the shadows of men; being worn out with hunger, cold, dirt, and filth, and bruised and enfeebled among stones and rocks”. He, and Rome, were in for a rude awakening.

Hannibal, aware of the fatigue of his host, roused them with a symbolic gladiatorial combat between Gauls, promising freedom and riches to the victor. The message to the army was clear. If they stood and fought, they too could grasp glory and dignity, and to this end he urged them with powerful words:

“On the right and left two seas enclose you, without your possessing a single ship even for escape. The river Po around you, the Po larger and more impetuous than the Rhone, the Alps behind, scarcely passed by you when fresh and vigorous, hem you in. Here, soldiers, where you have first met the enemy, you must conquer or die; and the same fortune which has imposed the necessity of fighting, holds out to you, if victorious, rewards, than which men are not wont to desire greater, even from the immortal gods. If we were only about to recover by our valour Sicily and Sardinia, wrested from our fathers, the recompense would be sufficiently ample; but whatever, acquired and amassed by so many triumphs, the Romans possess, all, with its masters themselves, will become yours. To gain this rich reward, hasten, then, and seize your arms with the favour of the gods”

Hannibal addresses the Carthaginian Army

The words were spoken, the journey endured, and the men were ready. It was time to court destiny.

Scipio, wary of the danger that Hannibal might incite the Gauls to war against Rome once more, moved to intercept him near the River Ticinus. He would there pay dearly for his poor estimation of Carthaginian horsemanship, as Hannibal’s concealed Numidian cavalry pounced upon the exposed Roman skirmishers, or velites, triggering a pell mell rout that disrupted the Roman countercharge.

In the chaotic mêlée, the consul himself was badly wounded, and spared death only by the duty of his son, also called Publius Cornelius Scipio — the man who would one day deliver Rome from the abyss.

Hannibal, his forces swelled with ever growing numbers of Gauls eager for Roman blood, seized the initiative. Mere weeks later, he baited a major Roman attack on the frozen banks of the River Trebia, a little before Christmas 218 BC.

The Roman force, led by the second consul, Sempronius Longus, was formidable. 18,000 Roman troops were supported by 20,000 Italic allies and additional auxiliaries. Combined with the political ambitions of Longus himself, and his unwillingness to share the glory with his wounded colleague, hubris led the Romans to confront Hannibal’s deadly provocations, leaving the safety of their camp to cross the icy waters of the Trebia.

So crippling was the cold that the Romans could scarcely hold their weapons for the numbness, as the well-fed and rested Carthaginians, buoyed by a devastating elephant charge against the Roman left flank, destroyed Rome’s first serious line of defence.

For the first time, Roman confidence turned to concern. New consular elections yielded new leadership — Gnaeus Geminus and Gaius Flaminius — who promptly raised new forces and commenced the fortification of Italy.

Hannibal, though suffering from the loss of one eye to gruesome illness, nevertheless tightened the screws on the object of his vengeance, ravaging Roman lands across Etruria (Tuscany) as far as the next great natural redoubt of Italy, where the mountains of Cortona meet the Lake Trasimene.

The army of Geminus was far away at the Adriatic coast, while that of Flaminius, selected by Fate for ruin, was stationed at nearby Arretium. Learning that Hannibal was near, Flaminius at once pursued with such haste that the necessity of proper reconnaissance was fatally discarded. Thus one day in June, 217 BC, as the legions of Flaminius were unwittingly caught between the lake and the mountains, Hannibal, whose forces were partially concealed by the mist rising from the Trasimene, sprung a second terrible trap.

With a great shout, the Carthaginians fell upon the Romans from all sides, as the command of the latter was hampered by the poor visibility and resulting confusion. So absolute was the din that none present were aware of the powerful earthquake that shook all Italy at the moment of battle. Pinned against the lake, many Romans preferred death in the Trasimene to the prospect of Carthaginian wrath.

So with the rising of the sun and the lifting of the mist, the grisly sight of fifteen thousand Romans (along with Consul Flaminius himself) lying dead on the field heralded the second great disaster to befall Rome…